12 Minutes with Jafar Panahi | Salome Kikaleishvili

“To Georgian filmmakers I want to say: dictators always get tired sooner than artists.”

- Jafar Panahi

For more than two weeks now, Iran has been swept by a powerful wave of protests. “Revolution in Iran,” “Death to the dictator”— such slogans circulate widely across social media. In the videos, brave Iranian women light cigarettes with the burning portrait of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, tilting their heads gracefully to the side so that their loose hair falls even more strikingly over their shoulders.

I came across a joint statement online by Iranian filmmakers Mohammad Rasoulof and Jafar Panahi. They called on human rights defenders and members of the media to help the people of Iran—especially after the regime cut off internet and phone communications and opened fire on the protesters. On January 14, the Iranian state also announced the execution of 26-year-old Erfan Soltani, who had been arrested during the crackdown. “History bears witness that silence today will have regretful-consequences in the future,” the directors write.

I was at the Cannes Film Festival in 2010. I remember that at the opening ceremony, as a sign of protest, an empty chair was brought onto the stage and placed next to the members of the jury. On the white chair, a name was written: Jafar Panahi.

Two months before the festival, the Iranian government had sentenced him to six years in prison for “propaganda against the Islamic state” and banned him for twenty years from making films, leaving the country, and giving interviews. It was already his second arrest.

As a result of the international outcry sparked by this case and the countless letters sent to the Iranian government, a few months later his prison sentence was commuted to house arrest. He was not allowed to leave his home, yet he still managed to make films: dictating shots to his cinematographer over the phone, keeping spare empty memory cards ready in case they had to be destroyed in front of officials, hiding files on his laptop, using coded language. “I found a form,” he would say.

He was arrested for the third time in July 2022, when he went to Tehran’s Evin Prison to inquire about the detention of Mohammad Rasoulof (the director of The Seed of the Sacred Fig). He was told that his 2010 sentence had never been fully served, and was imprisoned for another seven months.

“If it weren’t for prison, I would not have been able to create these characters, and perhaps I would never have made this film. So this film is not only my achievement, but also the achievement of all those who put me in prison,” says Jafar Panahi.

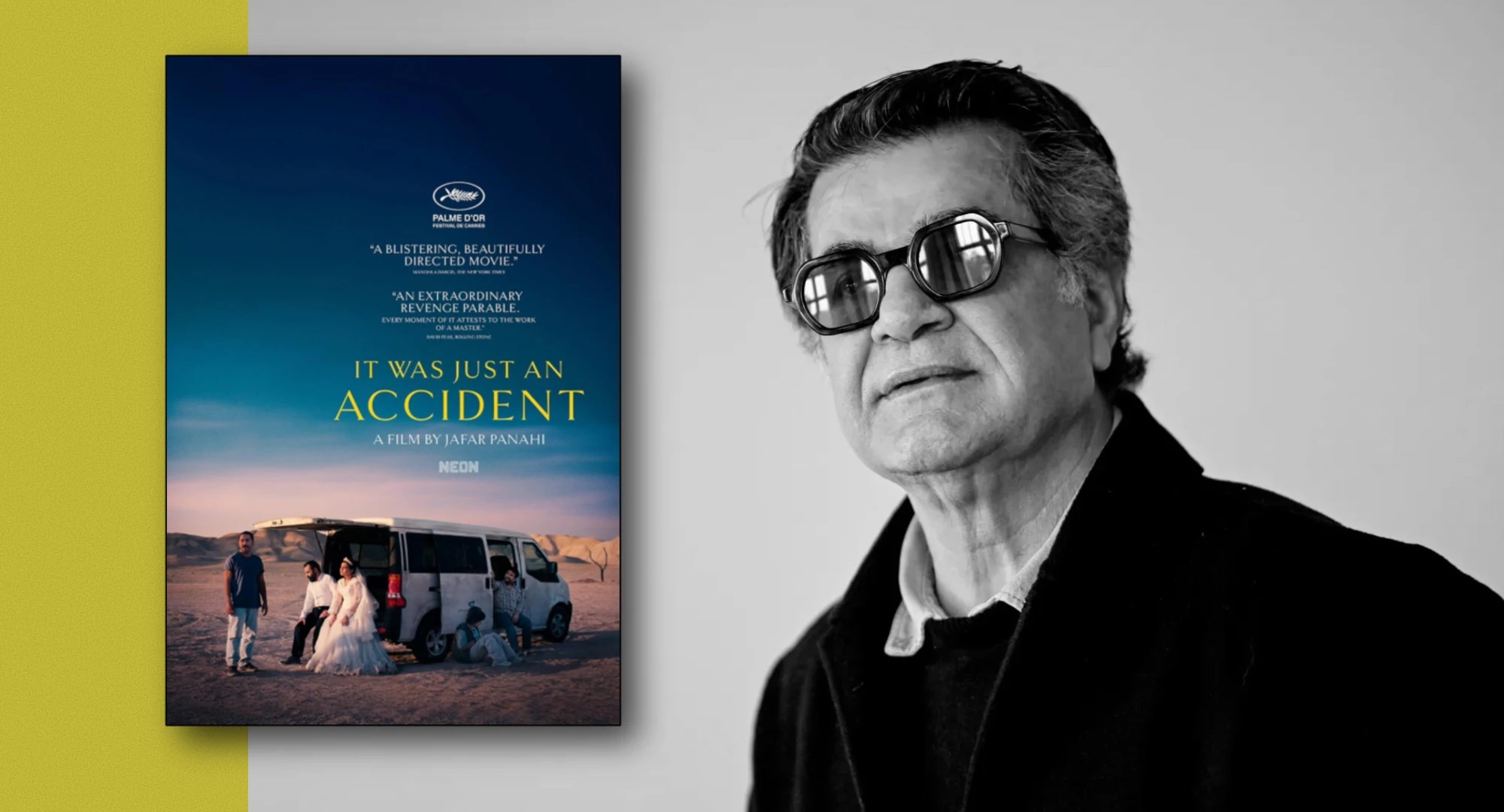

The film is titled It was just an Accident. In Cannes, it was greeted with a ten-minute standing ovation and went on to win the festival’s top prize, the Palme d’Or. Panahi, who found himself once again in the Grand Théâtre Lumière after twenty-two years, felt a sense of guilt. Unlike many of his colleagues, he was “outside.”

It was just an Accident was shot in secret. To edit the film, Amir Etminan had to fly from Istanbul to Iran, as transferring the footage digitally was impossible—the internet in Iran is under strict surveillance. Etminan could not bring professional equipment into the country; he was only allowed to carry his personal laptop and a few memory cards. Installed on his laptop was Adobe Premiere Pro, a video-editing program banned in Iran because it is foreign-produced. “If they had discovered it, I knew they wouldn’t kill me—at most, they would arrest me,” Etminan later told a Forbes journalist.

Each day he transferred the footage onto external hard drives and compressed the files so they could be edited on the laptop. The full material he delivered to Panahi, who hid the recordings somewhere. Meanwhile, as Etminan himself recalls, he edited the film at night in what he calls a “safe house.”

In addition to winning the Palme d’Or at Cannes and receiving nominations in three categories at the Golden Globes as well as from the European Film Academy, It was just an Accident is one of the best films of 2025.

The film tells the story of Vahid, a mechanic who, years later, comes face to face with the man who once tortured him—an interrogator responsible for questioning political prisoners—and kidnaps him. He wants revenge for the pain, the torture, and the brutality he endured during the interrogations. He wants to bury him alive. But first, he must be certain that this is indeed the same man. So he decides to tie the kidnapped figure up, lock him in the trunk of his car, and drive around to visit others who once shared his fate, asking them: “Look closely. Listen carefully. It’s him, isn’t it?”

Who is the perpetrator and who is the victim? Can physical pain, humiliation, and a shattered life trap you in an endless exchange of these two roles, or is it still possible to break free from this cursed cycle? These are the questions posed by Panahi, who himself was interrogated many times by the Iranian police, as he recalls his own experience: blindfolded, sitting in an empty room, listening to the questions of an investigator standing behind him. Two hours. Three hours. Sometimes even eight.

After the screening, he observes the audience’s reaction. He says that, in general, people respond very differently from place to place, yet with this film the viewers’ responses left him with questions. What is it that they like so much about it? Why do they receive it with such warmth? Is it the plot? No. “Simply put, today’s world smells of war. For some, this film is a memory of the past; for others, it is the present, their reality; and for some, it is the fear of the future – the fear that something like this could happen in their own country as well.”

He says that after this, he will make a film about war. But he will have to do it outside Iran, because working like this – underground, in secrecy, dictating into a phone – will not be possible; this film will require far greater resources. So when he is asked about filming abroad, he begins to speak about this project. “I know for sure that it will be a very good film, and that it is absolutely necessary to make it now. It will be the most humane film about war,” he adds in the end.

In 2012, he was awarded the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought by the European Parliament. Panahi is one of the very few directors who have won the top prizes at all three major festivals: Berlin, Venice, and Cannes. His films are well known in Europe, and critics, at the mention of his name, instantly grow alert.

In early December 2025, the Iranian government brought yet another charge against Panahi for “spreading propaganda against the state” and, in absentia, sentenced him to one year in prison. He is now in Berlin, helping a friend with film editing, then will go to France to renew his visa, and afterwards plans to stay in the United States. He is loved in Europe and would have no difficulty finding a new home, but he is not particularly fond of the idea of making films outside his homeland—though, he adds, nothing is impossible. To make a film in another country, he says, you have to feel and know the environment; whereas he himself, wherever he goes, is either at a festival, in a screening hall, or in a hotel room giving interviews. “If I make a film outside Iran, yes, it might not be bad,” he says, “but it also won’t be the kind of film I would truly like.”

***

I met Panahi shortly before the New Year, while working as an international voter for the Golden Globes. I knew I would have very little time to talk to him. Protests had not yet begun in Iran, but given what was unfolding in Georgia and Panahi’s own experience of living and working under an authoritarian system, the choice of topic was never really in question.

Salome Kikaleishvili: I don’t know if you are aware of what is happening in Georgia. For more than a year now, people have been standing in the streets, demanding justice, the protection of human rights and freedom of expression. They are being arrested for blocking roads, for speaking out. You yourself have been imprisoned, your films are still banned in Iran, and just a week ago an Iranian court sentenced you in absentia to one year in prison. Where do you find the strength to keep making films?

Jafar Panahi: To be honest, there is no single universal recipe that would work for everyone. It has to emerge from within the country itself, through the activity of artists who live there, who know their environment well and understand exactly which questions need to be asked and answered. People in one country cannot tell people in another how they should act; in that case, the formula will be false. But the first thing one must do is to ask oneself honestly: who am I, what do I do, and how do I do it?

Let me give an example from cinema. There are two types of film directors. One observes what the audience wants, what it likes and expects—whether it is action, drama, or any other genre—and makes films tailored to that taste.

And then there is the other type, who says: I make the film I want to make; let the audience come and find me, and adapt to my taste.

The first type makes up about 95% of film directors in the world. The second type—those who say, “This is how I am going to make films, and I am absolutely certain about it”—account for only about 5%. Once a person decides which side they are on, they can then find the way to do their work as well as possible, even under the most difficult conditions.

Salome K: You know this better than anyone, and you also know the price of such a choice. In one interview you said: “I count the days until I can return to Iran. I can only live in Iran.” And now, once again, you will have to live without Iran for a long time.

Jafar P: Of course, everything has its price. This is what artists sign up for. The government may no longer allow you to work; it may make the conditions extremely difficult. But once you accept this reality and take it unconditionally, a way out begins to appear on its own—new paths and new directions open up. Then you simply choose which road you want to take.

Salome K: In our case, one of the major waves of protest was initiated by artists. People from the film community are still actively protesting, and the actor Andro Chichinadze is in prison. How does one resist such a machine? By working? By creating? Or by standing in the street? Sometimes the search for these paths eats away at you from within and leaves you feeling lost.

Jafar P: There is one thing I want to say to Georgian filmmakers: do not give up. Dictators always get tired sooner than artists do, because artists are creators, and creators always find a way. Everything they do generates movement, and that movement, in the end, turns into a force within society. This is especially true today, when there are so many resources and so much technology available. With the right approach and the right mindset, it is possible to go very far.

Salome K: So far that one day the perpetrators might simply disappear?

Jafar P: Unfortunately, no matter what we do, autocrats will not disappear. They will always exist in this world. But artists will always exist too. And artists do not bow their heads to dictators.

***

Somewhere I once read that there are two types of cinema: entertainment and intellectual. And that beyond them, there is a third one – Iranian cinema, as a tool for fighting totalitarianism.

Cinema as an obligation to fight for freedom.

P.S. In an interview with Variety on January 9, Panahi said: “I have to return to Iran. I am a person who needs to be in Iran. I need to breathe the air there. I need to work there.”