"Don't give up until it's too late" | Interview with Belarusian director Mara Tamkovich

When I began working on the topic, I immediately thought of an elevator. You step inside, it weirdly squicks and an unpleasant thought creeps into your mind: what if it breaks down now? Then, as in bad movies, it stops you think, there, nothing’s going to happen, I’m safe, only for it to jerk again and plunge downward with a loud crash.

I enter the address and land on a website that, at first glance, looks like an ordinary news outlet: headlines, featured stories, brightly colored tabs. At the bottom of the page, there is an interactive map, dotted with red marks. I click on one Penal Colony No. 7. Zooming out, I watch the red dots multiply rapidly. I am looking for Colony No. 4. Katsiaryna Andreyeva (Bakhvalava), a journalist, sentenced to eight years and three months I find her. Listed below are her date of birth, the date of her arrest, the charges brought against her (disturbing public order and treason), and the day the verdict was delivered. Everything is meticulously documented: the judge, the prosecutor. At the very end, a red button reads, “Send a card.” I guess I can write a letter to her. To the right of the text is a large photograph: a young woman in a red T-shirt, smiling, her chestnut hair worn loose.

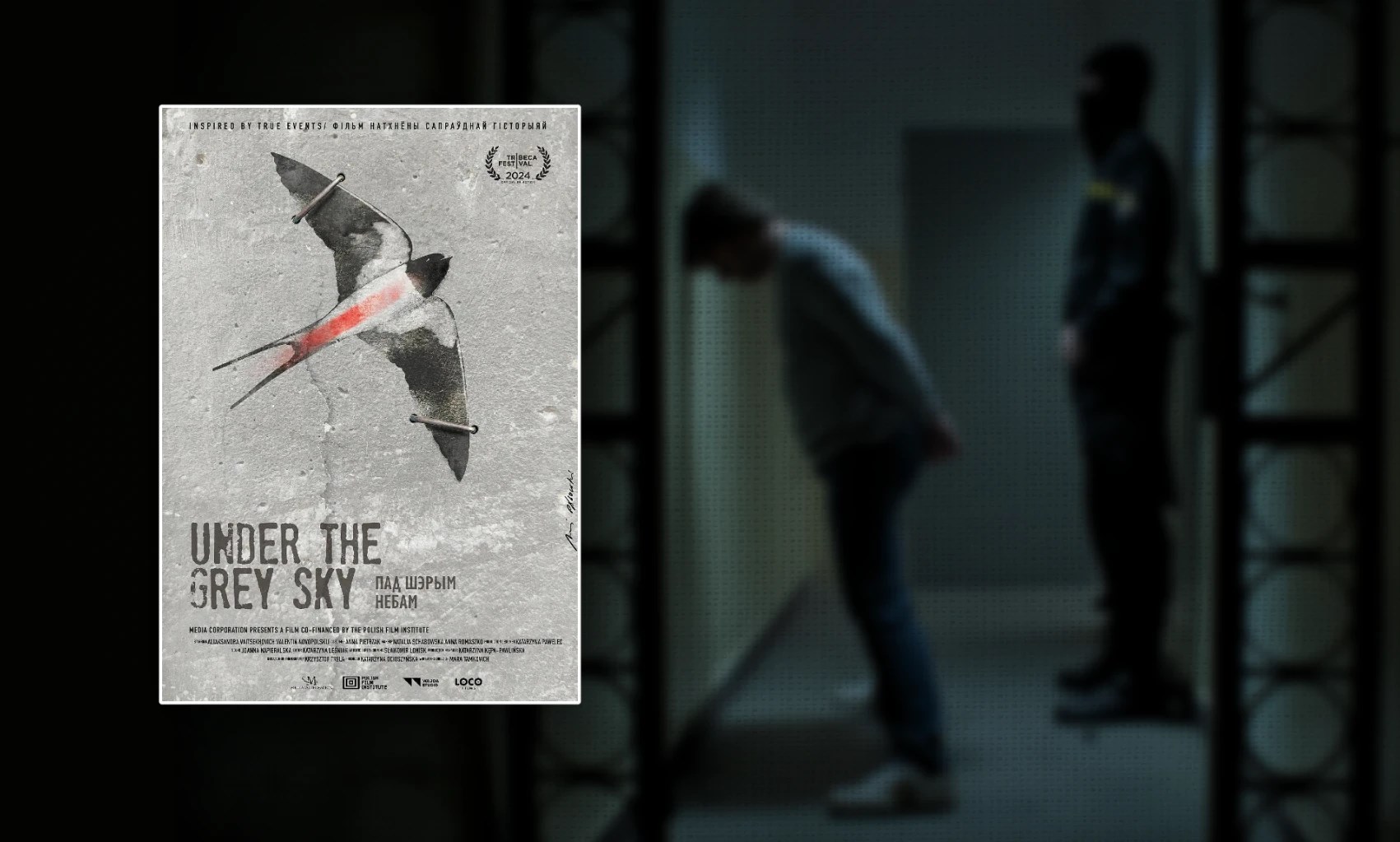

I first learned about Katsiaryna Andreyeva through a film by Belarusian director Mara Tamkovich, which I saw in the European Film Academy’s selection program. Under the Grey Sky has been nominated in the European Film Academy’s 2026 Best Debut category.

The film opens with documentary footage from Belarus showing the violent dispersal of a rally on November 15, 2020. The events were broadcast live by Belsat TV journalists Katsiaryna Andreyeva and Daria Chultsova. That day, mass protests under the slogan “I’m going out” took place at Minsk’s “Square of Changes” and in several other cities across Belarus, in memory of 31-year-old Raman Bandarenka, who had died a few days earlier. Bandarenka lived near the Square of Changes. On the evening of November 11, he saw from his apartment window special police vehicles arrive and masked men begin tearing down the ribbons in the colors of the Belarusian flag ribbons that had become a symbol of the freedom movement at the Square of Changes. Late that night, Bandarenka wrote in a Telegram group: “I’m going out.” He was beaten to death in his own neighborhood.

Mara Tamkovich with the actor playing the role of Ilya, Valentin Novopolsij

Tamkovich’s film has two central characters: the journalist Lena (a stand-in for Katsiaryna Andreyeva) and her husband Ilya (based on Andreyeva’s husband, fellow journalist Ihar Ilyash). After Lena is arrested for broadcasting live, Ilya is faced with a choice: he can flee the country and avoid an imminent arrest. Lena, too, is confronted with a choice. She is threatened with a harsher sentence and offered freedom in exchange for a confession. The entire narrative revolves around the couple how individuals confront the challenges that come with resisting the system, and where they find the strength to make such decisions. And what happens afterward, when the cameras are turned off and the hall is left in darkness.

...

Salome Kikaleishvili: Mara, in online materials you are often described as Belarusian-Polish. I know that you studied journalism and film directing in Warsaw, and that for nearly ten years you worked in independent media Poland’s Belsat TV and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. I’m curious: how did you end up in Poland?

Mara Tamkovich: I’ll start from the beginning. I grew up in the family of an independent journalist my father was a journalist since the 1990s so I’ve always seen life in Belarus through that lens. Lukashenko has been in power for over 30 years now, so for most of my adult life I have experienced different sides of what it means to live under an authoritarian regime: first as a child of someone who was dealing with oppression himself, then as a grown-up trying to work within this oppressive system as a journalist, and now as a filmmaker.

I left the country in 2006, after the protests. During the 2010 protests I was already working as a journalist. In 2020, I was watching events unfold from Poland, this time as a filmmaker.

A still from the film “Under the Gray Sky”

After the March 2006 protests, Poland launched a special educational program for Belarusian students who suffered different kinds of repression, because back then, for the regime, one of the most popular tools for influencing young people who were mostly the ones protesting was either making it very hard to get admitted to universities, since most of the higher education system in Belarus was state-run. Or the other option was this: if you were already a student, they would just expel you for whatever reason. If you were arrested, they expelled you for missing classes. If you were not arrested, they would wait until exams and then expel you anyway because of your name or something else. I had already faced some issues with the education system while I was still in high school, and I knew it would be extremely hard for me to continue my education. As soon as this program was announced, as the daughter of an independent journalist, and having personally documented incidents at my high school, I applied for the scholarship. I was invited for an interview, and suddenly they told me: pack your bags, you’re leaving in a week. “How is that even possible?” I remember thinking, completely confused. “So fast?”

I will never forget that day. The train was carrying 200 Belarusian students. There was a profound sense of uncertainty we were afraid, when we'll be able to come back and how it would be. It was a very, very emotional moment. I remember the date perfectly. 1 July of 2006. I remember every detail of that day.

So this is how I landed in Poland. Basically, the choice of the country was pretty random, and at this point it was just, you know, the opportunity presenting itself and that’s how Poland happened.

Salome: I knew nothing about Katsiaryna Andreyeva before your movie. While searching for information online, I came across the website of Viasna 96. It felt like a parallel world overwhelming in the amount of information and material, yet all of it revolved around a single theme: political prisoners, acts of defiance, security guidelines. There are countless black-and-white photographs: some people standing by the seaside, smiling with open, happy smiles; others with a cute Chihuahua perched on their shoulders; someone sitting at an office desk, eyes rolled upward as if to say, I’m exhausted. Today, every one of these people is a political prisoner. On each individual page, you find detailed information when they were arrested, for what, under which article of the law, and until when they are expected to remain in prison. Looking at these faces reminded me of a wall I once saw in Auschwitz, covered with photographs, evoking an overwhelming sense of fear and helplessness. Among all these stories, how did you choose Katsiaryna’s?

Mara: I began working on this subject with a short film, Live, which I made in 2021. I wrote the script after overhearing a phone conversation with my partner his voice is later used in Under the Grey Sky as he spoke about the logistics for Katsiaryna Andreyeva and Daria Chultsova’s live broadcast, when they were heading to cover the November 15 rally. I remember him telling me how they were now trapped in their apartment, unable to leave, hiding because a drone had spotted them, revealing they were filming. Then he described how special forces went door to door searching for them, the unbearable sound of doors being smashed in the stairwell. Listening to it all, it sounded like a bad American action movie.

Katsiaryna’s story was symbolic of what was happening in Belarus. When she was first arrested, she received a seven-day administrative detention. Later, the case was escalated to criminal charges. Honestly, today this no longer surprises anyone, but at the time, she was the first journalist during this protest to undergo this kind of treatment. We couldn’t believe it: “Okay, she’s been detained, but criminal charges? No, they can’t really give her two years.” When she was sentenced to two years, we said, “Yes, but for sure she will not be in prison for the whole sentence!” there was still a sliver of hope. By the time the short film premiered, we already knew Katsiaryna had been convicted of treason and sentenced to eight years and three months.

A still from the film “Under the Gray Sky”

I have never met her. When I started working on the film, she was already in prison. I know her only through accounts from colleagues and acquaintances, and through the letters her husband, Ihar, brought me. Of course, she hasn’t seen the film. We informed her through her family about the European Film Academy’s nomination for Best Debut; a few days ago they visited her. She couldn’t believe it: “Really? Are they watching this film? They’re interested?” That is the world she lives in - completely cut off from information. Her only means of communication are letters, which are, of course, censored, and meetings - only with family members.

Salome: You mentioned Ihar, her husband, also a journalist. As I understand, he acted as a consultant for the film. In one interview, you spoke about his “self-discipline,” how he never interfered with the creative process, recognizing clearly - on one side were him and Katya, and on the other, the film’s characters.You emphasized that distinction.

Mara: Yes, that’s how it was. I wrote the script based on interviews with him. On one hand, I was using these conversations to build the timeline, to reconstruct what exactly happened and how, but most of those talks were for me to understand his choices, dilemmas and emotions. I was trying to understand what the film is going to be about? In the film, I deliberately changed the characters’ names this is not the story of one particular journalist, it is the experience shared by an entire nation.

I specifically remember one of the conversations that led to a certain scene in the film. I asked him why he hadn’t left the country when Katsiaryna was arrested and he too was in danger. Why he had chosen to stay a decision that, objectively, was extremely risky and could have endangered him.

At one point, when I had exhausted all arguments to justify his choice, he said: “You’re looking at it all wrong. You think I did this out of heroism or to fight. No, it wasn’t like that at all. That was about saving my marriage. I just knew that if this is the kind of experience she has now and I leave and I land on this different planet in this different life, I'm not sure that our relationship, our connection can survive it, we will have two completely different lives and when she gets out what would the common ground be? I just wanted to stay on the same planet with her,” - added he at the end. And this was something that, you know, really struck me how it hadn’t even crossed my mind that this could be the motivation, and how strongly I had my own idea of what the aspects of that decision were. I didn’t even go there. So yeah, I also learned a lot in the process of these conversations, and some of them influenced the film deeply.

We cannot separate and cut out half of our lives, we cannot uproot personal relationships, and we cannot say that professional or activist decisions do not influence the other half of our life.

That’s false I know exactly what I’m talking about. I saw how my father’s choices influenced our family life, and how they reshaped the daily lives of the people around him.

Salome: How does Katsiaryna’s story look now, from this perspective? What is it in this story that frightens you most from this distance?

Mara: When Katsiaryna was first sentenced to two years, we were outraged. Today, five years later, we can say that those two years were almost a justification and that’s what frightens me: how the boundaries of what is “normal” can shift without us even noticing. Then we adapt to the new reality, try to make it work.

You know what else scares me? That two-year sentence provoked a strong reaction in society at the time; the story was widely covered in the international media. In September 2025, when Katsiaryna’s husband Ihar was sentenced to four years, hardly anyone paid attention almost no one. This is how the world has changed in the past several years.

What interests me now is exactly this: what happens in the lives of these people. They are there, in that intense, adrenaline-fueled protest, where extreme courage and extreme pain go hand in hand. But then it all ends the lights go out, and people return to their lives. And you stay there. My film is about that choice, the one that ordinary people, people like you and me face. The people who protest aren’t different; they aren’t made of something else. They are simply caught in a situation where making a choice is unavoidable, because you cannot remain neutral reality won’t allow it. I feel that people in Western Europe have lived, or we have lived, in comfort, where we didn’t have to make such choices dignity or safety? Freedom or morality? But that luxury is slowly ending.

Salome: You come from an authoritarian country. We, on the other hand, are now on this path. What power does cinema hold in such times? From your experience, can it become a tool for self-expression, or does it have the power to actually change something? What can be done when everything is shifting at a kaleidoscopic pace?

Mara: I don’t think a film or any footage today can trigger immediate change. I don’t see it as a tool any more. We have lost trust in images; sometimes we try not to believe what we see on screen, for the sake of our own comfort. But on the other hand, I truly believe that telling stories and sharing experiences can still bring about certain changes.

Mara Tamkovich with her parents at the station before leaving for Poland. July 1, 2006.

I remember a meeting with the audience after one screening in Poland. A Belarusian woman stood up and told me that nothing in the film was new to her she had seen it all with her own eyes. But the fact that she was now watching it in a room with Polish viewers gave her a sense that her story, her experience had a voice, that her pain was visible, and that when someone asks her about what happened, she can now respond:

“Turn it on and watch. This is how I felt. This is what I went through.” This is a way of building you know understanding and compassion in our very antagonized aggressive world, through sharing the experience, and cinema has a way to do it like no other art.

Salome: You once mentioned that your dream project is to make a series about Lukashenko coming to power. Why that specific period his rise to power?

Mara: Well, I think that the way our stories develop is like a stream, and when you are in this forceful stream, it’s very hard to turn away. If you try to go in the opposite direction, you feel enormous resistance. But at some point, you enter a moment of historical turmoil, when things can go in different ways. And I think the moment when we elected Lukashenko in 1994 was exactly such a moment it could have gone in very different directions.

What we ended up with was shaped by many factors. First, his own team underestimated him. He was perceived as someone easily manageable a charismatic figure who could communicate with people effortlessly and seemed likely to win; in 1994, Lukashenko was the opposition candidate in the presidential election. At that moment, we missed something, we didn’t see clearly. As soon as he came to power, every subsequent move was aimed at increasing authority, cemented his position, and eliminating threats. By the late 1990s, his political opponents were being physically eliminated. Who could have imagined that a man who was supposed to be just the “Kolkhoz” director (Soviet-era collective farm) in some remote Belarusian village would become Europe’s last dictator, a ruthless leader, remain in power for decades, and plunge an entire country into terror?

I have this childhood memory of mine when there was the second tour of the elections of 1994. I was six years old, staying with my grandmother near the Lithuanian border. It was late summer, but we knew a terrible storm was approaching that day. When we went to vote, I panicked: I cried, shouted loudly, begged my grandmother not to vote for Lukashenko under any circumstances. I don’t know maybe I had heard something, which is why I acted that way, I don’t remember. But I was crying so bad that basically I sort of forced her to vote for the other guy. After that, my father would joke: “Truth screams through a child’s mouth.”

I think this image the chaos and the pressure of making decisions is even more relevant today, as we are on the verge of making these decisions that might influence us for the decades to come.

Salome: Mara, where are your family members now, and when was the last time you were in Belarus?

Mara: My mother is in Minsk, as are my grandmother and the rest of my family. I last went there at the end of 2021. My father was already seriously ill, and I knew it would be my last chance to see him. At that time, my short film hadn’t been shown anywhere yet, so I could afford to take the risk. Now I can no longer return to Belarus. It would be a one‑way ticket.

Salome: In Georgia, people have been gathering every evening on the main avenue for more than a year now, protesting for freedom of speech, for freeing political prisoners, against the authoritarian absurd laws. We count the days exactly the way you do in your film 388, 389, and so on. You are someone who has spent decades in this struggle. What can you share with us something that might help? Tools for emotional survival, which we so desperately need right now.

Mara: Don’t give up until it’s too late that’s the first thing I would say to the people of Georgia. I’ve participated in many protests: the first with my father back in the ’90s, then others I attended myself in 2004, 2006, 2010, and later in 2020. These processes are sometimes accompanied by terrible fatigue and despair, when you can’t see any results and ask yourself what’s the point? Naturally, you can’t stay on the same emotional wave all the time. And this is exactly where finding a path of resistance becomes most important, because imagine that on the other side there are those who are not getting tired and if they take the liberties piece by piece at some point you will land in the street with no way out. You will land in a situation that is so bad, that you do not have any tools.

I remember the Rose Revolution in 2003 do you know how much that meant to us, Belarusians? We watched those joyful moments and thought, If the Georgians could do it, we must be able to too!

Later, we followed Ukraine’s Orange Revolution, full of hope. The fact that we still haven’t reached the place we’ve been striving for all these years doesn’t mean the goal wasn’t worth it. The path has simply proven far harder than we imagined.

This is about normalizing the struggle, making it part of your daily routine. But of course, there’s a dark side: seeing someone who has fought their whole life slowly weaken, losing strength. I’ve thought a lot about this, especially about those who have been fighting for twenty years. My father, for example, was an opposition journalist his entire life, and yet he never lived to see the changes he fought for.

But the main thing is that I really think, this is my personal approach, that we do it not only and not even mainly because we expect the result, but because we cannot do it any other way.

You know, you go out into the streets not because you think that today we will overthrow the government, but because your conscience does not let you stay at home. This is a personal choice. It’s not a choice about the result; it’s a choice about how you create your own identity through your actions. And if we see it this way if every day of protest is not perceived as a small loss because the result isn’t there, but as a small victory because today we again found the strength within ourselves to stay true to what we believe then, when we are alone, we can look at ourselves in the mirror and say, “I did what I could.”

And that is a great value. It does have meaning, and this is our only hope when we are facing evil systems that are much stronger than us, that have guns, that use violence, that are simply terrifying. This is our only hope.

...

Then she spoke about Aliaksandra Vaitsekhovic, who played Lena’s role. She is Belarusian and left the country in 2020, moving to Wrocław during the protests. At that time, she had just had her second child, and she had to make a choice she chose her family. I think that by playing Lena, she was trying to compensate for that decision.

Making this film was also important for Mara Tamkovich herself through it, she tried to overcome her own sense of helplessness. She wanted to know how she can help, what she can do if you're not within the country?

From the personal photo archive of Ihar Ilyash and Katsiaryna Andreyeva. Nanna Heitmann (The New York Times)

And indeed, what can I do? I’ve asked myself the same question many times, just like Mara. Sometimes I smile at our naïve protests in Lisbon, on Praça do Comércio, where a handful of Georgians gather. We stand there, holding placards beside a huge sound system with colorful lights, demanding the attention of tourists exhausted from photographing Lisbon’s most famous spot.

P.S. I was thinking about the conclusion of the article when I came across this letter, published in 2021 by the Press Club Belarus. Ihar Ilyash writes about his wife, just one year after Katsiaryna’s arrest.

Here are the excerpts:

“I fell in love with Katya when I felt we were in tune, had the same rhythm of life. She has an unlimited feeling of inner freedom. Our first date almost ended with detainment: after we left the coffee shop Katya suggested we should go to one of the election stations [events took place at the time of 2015 election]. And someone called the police there. When we left the police station, we laughed aloud”.

“Katya doesn’t complain about health or emotional pressure. It seems to me she is in a calm state now; it’s reassuring that she will hold on and will complete this journey honourably”.

“She hasn’t changed at all. I saw it during my long visit. She might have been reserved a little at first, but that’s what’s required of you in prison. And then all her emotions, mimics, gestures were just as they were outside prison”.

“It is prohibited to speak about daily schedules in all the prisons. I only know that Katya works at a factory in shifts and at all other times, they are sent to clean the premises or the prison territory or to the kitchen to sort potatoes”.

“She started training as a hairdresser on September 1. Katya honestly says she used to have all the free time at the pre-trial detention facility to write letters and now she can’t. She’s lucky when she can write two letters a week”.

“We have three main channels of communication: lawyer, letters and Viber calls. Yes, there is such an option in Belarusian prisons now. These calls allow to see and hear Katya for at least five minutes a week, to know how she’s doing. And our letters are for our thoughts, discussions, feelings”.

“What are we going to do when Katya is released? I think first of all, we will look at each other and talk a lot. Be together, not even go anywhere outside. We will be feeling each other. And then we’ll go on a trip across Europe”.

...

Ihar Ilyash was arrested on October 22, 2024. He was charged with involvement in extremist groups, which in practice meant collaborating with foreign media and thereby “discrediting the country.” During the trial, his articles were subjected to months of psycholinguistic analysis. On September 5, 2025, he was sentenced to four years in prison. On December 5, the Belarusian Ministry of Foreign Affairs added him to the list of extremists.

On December 14, Lukashenko released 123 political prisoners. Late that night, I wrote to Mara.

Katsiaryna Andreyeva and Ihar Ilyash were not on the list.

...

Salome: I remember a scene in the film with a song when Katsiaryna’s seven-day detention is extended to two years, and everyone, including his wife, advises Ilya to leave the country. He faces this choice to leave or to stay and suddenly the song begins. The lyrics, “I will stay here, I will go nowhere,” were incredibly emotional for me. It felt as if what I was watching on screen was not cinema, but reality one that my own country shares and that scared me even more. I felt that the words of the song now touched me personally.

Mara: That is the film’s only musical moment. “I was born here In the country under the grey sky” - this song dates back to the 2000s. I remember singing it as a teenager because it carried a strong sense of resistance, faith, hope, and everything else that comes with this desire to change the world for the better when you are a teenager. I am sure the characters in the film sang it many times in their youth. Now, my character is over thirty, facing an incredibly difficult choice.

The song evokes the idealistic vision of a new world he once believed in, and at the same time makes him aware of the cost of all that. But what can you do when you don’t know how to act differently, because all of this is who you are.

We Recommend