More Familiar or More Strange? | Interview with Erik Scott

Conversation with Erik R. Scott, historian of modern Russia, the Soviet Union and the global Cold War, professor of History at the University of Kansas, Director at the Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies, Editor of the Russian Review.

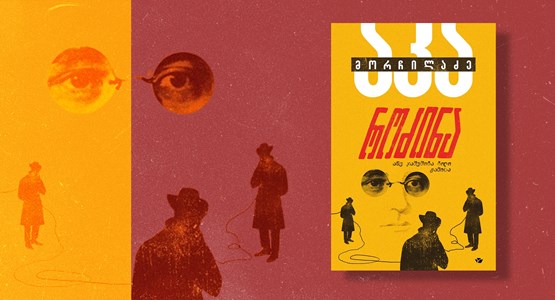

His first book, Familiar Strangers: The Georgian Diaspora and the Evolution of Soviet Empire was published in Georgian in 2025 by Ziari Press. Excerpt from the annotation: “Investigating Georgian political, cultural, and economic networks that spanned Soviet territory, the book views the evolution of the Soviet empire from the perspective of its most prominent internal diaspora.”

His latest book is Defectors: How the Illicit Flight of Soviet Citizens Built the Borders of the Cold War World. His upcoming work is concentrated on a history of the Soviet Union’s collapse and its aftermath from the perspective of sports.

Erik Scott visited Tbilisi in September, 2025 to present the Georgian translation of the “Familiar Strangers” at the Tbilisi International Festival of Literature.

Retrospective thoughts about forming Georgian identity

Question: When was your last time in Tbilisi, Erik?

Answer: I was last here in May 2023, when it seemed that public protests had succeeded in derailing the “foreign agent law.” It was, in retrospect, only a brief pause for Georgia’s ruling party, since the law was later reintroduced and Georgians have taken to the streets for the past 300 days to protest the government’s decision to suspend talks to join the European Union. So in many ways it feels that Georgia and the rest of the world is in a more difficult moment now.

Q.: The question about how the past can reappear and whether it is a challenge for a historian to know the past (events) as the temptation might be there to foresee what is going to happen next, because you know how something similar has already happened.

A.: I don't think as a historian I can predict the future. I don't think political scientists who often praise themselves for their predictions can predict the future either. As a historian, I think history is made by not only past patterns, but also by individuals as well as the unforeseen and sometimes chaotic events that no one expects. What historians can do though is to identify patterns. We can explore the ways in which the past is used by different people.

There has been a big interest since the collapse of the Soviet Union, and for obvious reasons, in finding a usable past for Georgia. The question of what ‘this usable past’ means changed dramatically while I was researching and writing this book. I was first in Georgia in 2001, during the Shevardnadze government. Then I was researching and writing when Saakashvili was in power. And I also returned to Georgia near the end of the 2008 war. Then I was finishing the manuscript under the Georgian Dream government. So you could see how each of these governments sought to create an usable past, which is not only about remembering, but also forgetting certain aspects of the past. Each of them has had to position themselves in relation to the Soviet past, whether as something that will be forgotten; or something that is a form of an occupation; or something that may be remembered more nostalgically – perhaps not as a whole program, but with a few selected elements.

Historians are generally commenters on these debates rather than participants, and I think we can provide some critical tools for people to think about things: to think about how we can analyze historical documents, how we can connect personal history, which can be extremely varied, to the big picture. We create these narratives of what happened, but the narratives are always contested, they are always selective, so we have to think about how we're choosing to construct them and what we're challenging.

In 2001 – 10 years after the collapse of the Soviet Union – when I first came to Georgia, there was a clear sense of rupture with the Soviet times. I saw this in discourse, in the way people talked about their past. But at the same time the impact of Soviet material culture was very obvious. And Soviet legacies could still be felt below the surface. Since then there has been a generational change and a good deal of narrative building. Under the United National Movement there was a big effort to frame Soviet occupation as foreign occupation. This was also an effort to align with narratives that were understandable in a European context, based on the Baltic models and the Polish model. And there was actually some really interesting research being done, but much of it was made to fit this narrative.

Now to be honest I'm less clear what narrative the current government is pushing. It's more an ideological hodge podge – a mixture of different, sometimes contradictory things.

Q.: Ajapsandali, perhaps?

A.: Ajapsandali! Certain elements of the past are combined with other newer elements. I don't want to say that it went from being about the Soviet occupation to a pro-Soviet position, because it's not simply a pro-Soviet position. But there's a softening of attitudes and perhaps an expectation being raised that Georgia can recapture some elements of how things were in its relations with Russia that might be beneficial. But there's also been statements made about the EU being a new Soviet Union by the Georgian Dream. So this new narrative that we are seeing is very eclectic and not completely logical, but maybe that’s what makes it effective in stoking both hopes and fears.

Q.: You mean effective for addressing certain populations, and / or certain geopolitical actors too?

A.: Yes, it might appeal to older Georgians as well as those who feel like they’ve been left out of the benefits of closer integration into Europe. I suppose it might also be a form of signaling to neighboring countries as well.

Q.: The term ‘familiar stranger’ can be reversed to position Russia as perceived so by Georgians. It is interesting how the proximity or intensity of attitudes towards this Northern neighbor of ours hardly changes – It is familiar, yes, but it is a stranger too. This reflection of mine is simply to admire the term itself in which the meaning fluctuates by choosing which word to accentuate more ‘familiar’ or ‘stranger.’

A.: Yes, and the balance between familiarity and strangeness can change over time, even as Georgia’s relationship with Russia changes. I think for many Georgians today Russia is seen as a detour away from Europe, since there is an acute sense of wanting to belong to Europe. But if we think about longer term history, one of the reasons why Georgian intellectuals in the 19th century were interested in Russia was the European factor: they saw Russia as a pathway to Europe. Now it's seen as a pathway away from Europe and a threat to Georgian sovereignty.

It's understandable why this is the case. There is obviously still a sense among Georgians – rightfully so – that Russia is an occupying power in Georgia. There are so many IDPs in Georgian society and people who know them and their families, this sense of trauma and traumatic displacement is still very real.

At the same time, I think, there is some romanticization among Georgians who lost certain benefits of the past and one sometimes hears praise for past Georgian leaders who were able to skillfully manipulate Russia to get benefits for Georgia. The Mzhavanadze period, in the 1960s and early 1970s, is sometimes spoken of fondly. Perhaps it wasn’t a golden age, but maybe some sort of bronze age when things were stable and the standard of living was felt to be increasing. There was of course a lot of corruption that was tolerated that made all of this possible, but it seemed to some people as a comfortable time.

It is interesting how you have used the concept of ‘familiar stranger’ to describe Russia, but this concept in the book is really about how Georgians are imagined by the Soviet Empire, and the extent to which some Georgians, not all Georgians, but some Georgians mobilized their culture and represented themselves to meet Soviet imperial needs. These representations then had an impact on the way Georgians saw themselves. Of course the Soviet Union didn’t describe itself as an imperial project, but it was an expansionist state that demanded loyalty to the party-state in Moscow and needed to emphasize its multiethnicity. It was not so much a Russian empire as an empire with ideology at its center, and Georgians served an ideological function in presenting a vibrant and successful counterpoint to the dominant Russian culture. These representations were funded by Moscow and they were supported by Soviet infrastructure and institutions. Georgians who operated within this system and stayed within the ideologically acceptable limits gained benefits, a degree of prestige, and sometimes even a level of autonomy with the somewhat closed system of the Soviet Union.

Soviet ideologues, of course, did not create all of this from nothing. What makes Georgia different from some other Soviet republics is that many of its cultural institutions existed before the Revolution. There was already a tradition of theater, a very well established literary tradition, a cinematic tradition, and the conservatory.

This played out in culture, and it also played out in the economy and in everyday life. Georgians had certain products that they had monopolies on, including tea and tobacco, which met Soviet demands and were marked as exotic goods from “sunny Georgia.” As for the Georgian food, in some ways it was a sort of replacement for foreign cuisine, which was ideologically not acceptable for Soviets.

Q.: Did you study other diasporas too of the Soviet Union while working on the book?

A.: I actually looked at Georgians not only in comparison with other diasporas in the Soviet Union, but also in comparison with other diasporas in other empires to understand what I was seeing in Soviet and Georgian history.

So for example, in the Ottoman Empire I looked at the role played by the Phenariot Greeks or by Armenian elites; in the British Empire I looked at roles played by Irish and by Scottish groups whose countries were essentially colonized by England but then became very important agents of the Empire in India. And then I also looked at Parsis – people of Persian descent in India who ended up becoming very important commercial middle men under British rule. So I think in many different empires we have groups that are both colonized by the empire, but who then also participate in the empire's elaboration. I think it's important to give those groups agency; to look at them as people who have choices – they don't have all the choices in the world, but they are making choices about how to relate to imperial power. Some are choosing to oppose it, and some are choosing to participate in it.

I did a lot of reading about migration and diaspora to understand what I was seeing in the Soviet Union, because in the Soviet Union, the use of the term “diaspora” has been very limited. Until very recently, it was only used to describe groups that were forced to leave and had no homeland, like Jews, or Germans and Poles in a Soviet context.

I developed the notion of “internal diaspora” to describe a different type of group like the Georgians. They moved beyond their homeland, but their homeland was in the same political unit as the host society, and so they were able to move back and forth easily. They had in their homeland political patronage networks, economic resources, and cultural institutions. They were allowed in a Soviet context to express ethnic difference, because Georgian was an officially recognized language. There are of course limits on the extent to which they could use the Georgian language. For example, they were not allowed to open Georgian language schools in Moscow until the end of the Soviet period. On the other hand, Soviet passports clearly marked Georgians born in Moscow as “Georgian,” thus accentuating their ethnic difference.

I think all these factors are important since the Soviet Union really wanted to represent itself as multiethnic, not only for its own populations, but also for the world, especially in the cold war era, when there was a huge effort to appeal to post-colonial nations. It was very important to show that Soviet leaders were not simply another group of colonizers; that Georgians could occupy a very useful position, that they could be both represented as very different yet intrinsically Soviet, even reaching the height of Soviet power in the time of Stalin.

Then there was a set of Soviet needs, and a certain repertoire that Georgians brought with them to Moscow to meet these needs. This created opportunities for members of the Georgian diaspora. But then again if you were a performer, if you were a chef, or a filmmaker and if your audience was Soviet, dominated by the Russian majority, then you had to make some changes to what you were offering so it became understandable. This meant compromises which I think were not so readily seen early on, but over time came to be a concern for the Georgian intelligentsia. By the late Soviet period, many came to feel that they were participating in a compromised and watered down production of Georgiannes.

Q.: And then, in the new reality, this ambivalent Soviet legacy became so hard to carry that some people were really keen to follow the grand national narrative building process under UNM’s – cancelling the ‘collaborative’ (negative) part of the Soviet past, and highlighting more (positive) parts of the history in which anti-Soviet resistance is more powerfully obvious. But after overcoming even this phase of black or white, either-or thinking, there should be certain assumptions for Georgians to make, I think (I might have used the term ‘learning history lesson’ here, but I won’t).

A.: Indeed, we need to move beyond black or white, either/or thinking. There are many contradictions to living within an empire, and I think the diaspora part adds another level of complication because this is not only about Georgians in Georgia, but this is about Georgians living in Russia and Ukraine, and these are groups that had their own dynamics.

Also, I want to emphasize that this was not a project of all Georgians all the time, but this was a project of certain groups within Georgia that saw in participating some benefit. Some believed in the revolutionary utopia promised by Soviet slogans, and some sought material benefit, career advancement, artistic achievement. Others merely sought to survive. At the same time, others stood in strong opposition, opposing the Red Army’s invasion, rising up in 1924, or more subtly undermining Soviet authority.

So, I think, one thing that is clearly seen here is the multiplicity of perspectives on the past: Georgia is not a unitary actor, its full of many different people who need to be understood in the context of their times.

And I'm not interested in judging, but in understanding, and I think that's really important not only for Georgia, but for any country, and perhaps a better aim than reducing the Soviet Union to a “usable past.” Because I've already seen how what is useful now is different from what was useful 10 years ago, or 20 years ago.

We don't want to replicate a Soviet model where there was one interpretation of history that was correct; we don't want to replace that with a counter narrative in which ‘everything has to be rejected 100%.’ In reference to Georgia’s singing traditions, I think we need a more multivocal and polyphonic sense of history.

Q.: It is important the tone and position of the perspective – from which Georgians are perceived. They are seen from the perspective of the Empire - they are familiar strangers to others. But while working on the book did you notice a change of perspectives. Did you see some events with Georgian diaspora eyes?

A.: I think every diaspora has to navigate between how they see themselves and how they're seen by other people. And there are a number of theories to understand the latter, including Edward Said’s notion of Orientalism. I think there are many ways in which this might be seen as applying to Georgians, especially if one looks at nineteenth-century Russian literary portrayals of Georgians as “exotic” and the Caucasus as a land of beauty and violence. But if we take Said’s argument to its logical conclusion, it suggests that Georgians had no agency whatsoever, had no choice about how they were represented, no voice of their own besides how they were portrayed.

I think it’s more helpful to think about Georgian representations as an imperial hybrid in whose creation Georgians played a part. You can see this especially in the cultural world. For example, the Sukhishvili dance ensemble is a group that is both very Georgian, but very much shaped by its imperial context. Sukhishvili had experience in Russian ballet and used that training to choreograph unmistakably Georgian dances.

You can also see people playing with dominant representations and even subverting them, and I've always really admired the works of Georgian film directors who do so, particularly, Otar Ioseliani. In Giorgobistve, the film is set around the wine factory which makes a product – Georgian wine – that's obviously for imperial consumption. The film shows all the compromises this entails in terms of quality. And Niko, the main character, is not some sort of macho Georgian guy, but he's a naive character who is in some ways very peculiar, but in other ways very honest.

Ioseliani was a master of operating within this Soviet system to make the movies he wanted to make. He had a lot of support within Georgia, and when his films were sent to Mosfilm he always framed them in a way that was supportive of communist ideology. And then he went ahead and made the film he wanted to make, even if it would only end up being shown to a small circle of people. Over time, however, he came to see the limits of the Soviet system more clearly. And he wasn't alone. By the late Soviet period you can see in Georgian cinema a crisis of authenticity, of being a small nation having to perform for the audience that had a pre-existing expectation of what it wanted to see. I’m thinking here of Tengiz Abuladze’s Repentance, which had a major impact across the Soviet Union, but also of Irakli Kvirikadze’s film The Swimmer, which was never released but is one of the best examples of this sense of crisis among artists and intellectuals in late Soviet Georgia.

After Stalin's death, the Soviet Union does begin to look more like a Russian Empire, at least in terms of its leadership. There was a growing sense that this was not the same project it was before, and there was a sense that people in charge were far less capable than the members of the intelligentsia cultivated by the state. The early Soviet Union’s revolutionary foment had begun to cool, becoming solid and sort of constricting. I think there was also a growing sense among Georgians of the world outside the Soviet Union. Many of these people who were familiar strangers in the Soviet context began going abroad, as artists, as intellectuals, as athletes, as performers encountering a broader audience and encountering different reactions to what they were doing. Sometimes they were even perceived as Russians, which was a rather unpleasant shock. There are many newspaper accounts of Georgian dancers going abroad and being described as Russian dance ensembles. Or Georgian football players being described as Soviet or Russian. So added to the sense of disenchantment is a growing sense that there's a world beyond Soviet borders where Georgia and Georgians are less well known. Ioseliani is well aware of foreign audiences, because his films are, in part, directed at foreign audiences at prestigious film festivals in France and Italy. Over time the feeling grew that being a “familiar stranger” in a Soviet context was a constricting representation rather than empowering one, and its prestige began to weaken over time.

Q.: Cultural national identity becomes confinement. It is no more enough for expression of nationality and political agency also is needed to feel represented.

A.: Yes, ultimately the terms of the cultural representation were too confining. There was a perpetual emphasis on folkloric representation, on being like an ornamental or decorative nation on this bigger Soviet tree. And Georgian artists and filmmakers began to push against Soviet political demands, to engage cultures beyond the Soviet Union, and to move from culture to politics. Robert Sturua looked to England’s Shakespeare, imbuing his plays with contemporary political meaning for Georgians while mixing Georgian and foreign culture. And some of these artists even became political figures. Abuladze entered politics, as did Eldar Shengelaia. It seemed like a natural progression from cultural intelligentsia to participating in politics when the opportunity arose.

Q.: So is nationality always a political concept?

A.: Yes, it's a political concept that has cultural and economic manifestations. In my book, there is the Soviet definition of nationality, which was developed with political motivations; in some ways it was about making a compromise with local populations to encourage them to participate in the Soviet Union. There was of course an independent Georgia before the Red Army's invasion, so by recognizing nationalities and in some ways encouraging Georgian cultural production, the Soviet authorities show that they're making concessions to locals. They also used nationality as an instrument of rule, sometimes giving certain national privileges, other times taking them away. Some nationalities were declared to be enemies of the people were deported, some received certain benefits within a certain territory, but there was effort to rule through nationality, and they tried as much as possible to link nationality to a set territory.

I don't think any nationality can be defined without some reference to culture – usually language, shared history. Stalin himself wrote about what made a nation. I'm not going to adopt his perspective entirely, but these were important characteristics in the twentieth century: territory, culture, history, language, forms of dress, national cuisine. All these were articulated within the Soviet Union as part of its political project of building nations and guided them to a communist future.

What some historians have ignored, but what I think is important, is the economic bases of nationality, the culture industries that are funded and that produce culture, the economic resources that shape the way territory is incorporated and the choices that people can make on that territory. We see this in the promotion of Georgian cuisine in the Soviet context, which had political uses and was seen as an expression of Georgia’s distinct culture, but also depended on goods and ingredients that were produced in Georgia. The famous restaurant Aragvi in Moscow was supplied directly by Georgia’s ministry of trade when it opened, and Georgia’s food and wine industries soon supplied customers across the Soviet Union.

Q.: This is my last question to you from our colleague, Giorgi Chkadua: If we are guided by the concept of historian Pierre Nora, in a shrinking world, the distance between certain territories has become so short that a person can approach the “center” without moving from their current location. What new ideas would you think about while keeping this concept in mind?

I would also add: How do you see geopolitical shifts from the point in the world where Georgia is located? And, at the same time, from the outside looking in, how do you view the struggles Georgians are fighting here?

A.: I think this is a question about identity and also about geography. In my 20-25 years of coming to Georgia, I’ve found that it is a place where one feels the impact of geopolitics in everyday life in a way that is rather dramatic. Perhaps especially for an American, since we have the opposite issue: America's problem is that the rest of the world seems far away, and some Americans think we can just do things on our own. But here you feel not only Russian influence, but you feel proximity to Turkey, you feel Chinese investments, some connection with Iran, to Arab countries, and also connections with Ukraine, with Baltic countries. It's just palpable. At times it seems almost like an ongoing geopolitical experiment, and of course no one likes to be experimented on. People want to be able to make their own life.

That said, I think there are ways in which geography might matter less than it once did. With the internet and social media, people can participate in conversations and debates that take them far beyond where they are, for better or for worse. This sense of moving beyond territory is not entirely new. One of the things I look at in my book is how Georgian diaspora was able to represent itself far beyond the territory of Georgia; how in some ways it created a deterritorialized and reterritorialized identity that not only made Georgia more Soviet but made the Soviet Union Georgian in some ways, or added a Georgian element to it.

But now it is a very difficult time, it's a very tense time. I think we are seeing what we've talked about for many years intellectually, but now we're feeling – a multipolar world, a world in which the rules them of the international order are beginning to fall apart or are not being enforced, certainly not by the United States and its current president, who seems happy to walk away from from the international order that the United States helped create after World War II.

So I think it is a very insecure time for Georgians. I really hope that Georgians are able to build a political reality that they deserve based on the incredible human potential that I see here and the impressive intellectual, cultural, and entrepreneurial spirit that I see here. I also hope that Georgians encounter an EU that lives up to its potential also.

Obviously right now the EU cannot offer more given the actions of the current government. But I do hope in the long run the EU will honor its obligations and its commitments if Georgia does pursue a path toward Europe.

We’ve ended with a discussion of contemporary issues rather than historical ones, but history is inseparable from present day concerns. It is written in the present but with an eye to the past. It’s a way of asking questions to find out how we got here and where we can go from here. Let’s hope it helps us create a new kind of politics, with space for curiosity, dialogue, and understanding.

We Recommend

Dato Jishkariani's Sayings | Episode 05

19.04.2025