Mountain Girls

06.09.2017August 11, Shuamta Day

Zemo Achara, Zortikeli

The village elders sit on long wooden benches facing a succession of houses scattered across a mountain slope in front of them. Some of them, with arms propped up on the fence, look outward at an open space between two peaks.

A stage is being set up in the field. Several days of rain covered the entire village in mud. A wrestling area encircled by white tape is full of small puddles. A group of equestrians appear across the narrow river on the main road. The horses are being prepared for a race.

The engagement and wedding season begins on Shuamta Day. After the horse race, in the midst of an enchanting feast, a bride and groom festively attired and mounted on horses will gallantly trot down to a road packed down by hooves.

“We have an older bride this year, she's twenty-five-years-old,” a thin girl wearing a gray dress and headscarf tells me with a smile.

“I was fifteen,” she says, as she corrals the two-year-old son by her side, grabbing his arm so he doesn't escape onto the horse track.

A horse rears-up on its hind legs on the main road at the edge of the upper valley. The crowd is shouting and yelling in the field. “He's been saddling-up his horse since the last race. He came in third on previous race, now he wants to be first,” she says quietly, as she looks at her husband while holding her son's hand even more tightly. “I took a course on the Quran in Batumi, when some elderly men came to appoint him. I had seen the boy, but didn't know him. I wanted to continue studies in Turkey. Though, the moment my parents came in to discuss the marriage with me, I realized everything had already been decided. There was no other way.” She was just turning seventeen when she gave birth.

Children are dancing in the mud under the stage. Ricky Martin's ‘All I Need’ echoes in the valley as the music booms from the amplifiers. A handful of women stand on the other side of the racetrack wearing dark head coverings. Some are covered in the old-style, with a double head shawl made of black gauze. Spurred on by the wind, clouds of mist occasionally roll in from the mountain peaks. At times, the fog covers the children on the stage and turns the group of waiting women into phantoms.

Some shouts are heard: “Look, they're coming!” The bride and groom approach the arena with the bridal party. A white, lacy dress is worn by the girl. But she more resembles an older woman with her sharp makeup: pink lipstick, eyeliner, and dark green eye shadow. Engagement gifts sparkle on her breast, wrists, and fingers. After while even the children stop dancing and focus their attention on the bridal party now enveloped in the mist.

Adjara is one of the regions of Georgia where children get married most frequently. Information is now reaching these remote villages, and along with time The old customs must lose their resolve along with time, but it is not enough to change what is happening in those remote villages.

“We too will soon dress you up like a queen in this manner,” a mother tells her eleven-year-old daughter in laughter. Her aunt had already been engaged that day. A group of agitated people spill out onto the balcony of an old wooden house from the engagement feast. The women are still bustling about the table. In the bedroom, the bride, along with a few female relatives, looks at her gifts. She takes out a pair of colorful satin slippers, some pink linens, colored blouses, cosmetics, and removes a box of sweets from a checkered bag, setting them on the bed. Occasionally, a man looks into the room, which is divided by a thin curtain. The women raise their voices or suddenly change the topic. The bride's grandmother sits on a low wooden chair smiling at her. She's the one who usually disrupts the silence.

“All of us wait to be a bride from early on my girl. Who asked us anything? Who advised us how to act with a man for the first time? They don't talk to us about this even now,” a neighbor girl says at a whisper. “All of us have a [satellite] dish at home,” the grandmother answers with a smile. “You watch TV series and go about with a cell phone. If no one were to give you advice, you would understand many things on your own. Times are different now.”

Tsitsino and her daughter are standing right there. Tsitsino was 12 when her parents unexpectedly announced to her that they’d marry her off. “I was happy,” she says shyly, “I wanted to be a bride.” She had saw her future husband for the first time at the engagement party. A wedding was put on when she was fourteen. Soon after she moved in with her husband. Tsitsino has two children. She spends a few months each summer in the alpine meadows with her husband's family. They take livestock out to pasture in the mountains. In August, the meadows are harvested and as soon as the weather gets colder, the nomadic families return to the lowlands.

An ox lies on its side on the edge of the road, they are filing down its hooves. The sound of a lathe is heard from a blacksmith shop. They are changing the horseshoes on the horses in preparation for the race. There are children playing in the yard – four of them to be exact. They also have a fifth brother, but he’s sleeping. Nargizi - their mother - was kidnapped when she was fifteen-years-old.

“No one returns a kidnapped woman back to her home.” At twenty-six years of age, she has six children.

“Go on woman, bring something out for the guests,” the father-in-law advises her. Nargizi stands in one spot without moving and looks at us. “I gave birth to him forty days ago,” she responds to a question asked a little while before. “My mother helped me give birth here at home and left.” She puts a pacifier in the mouth of the infant in the cradle and he sucks on it intensely. His five or six-years old sister is standing near the cradle. The girl tucks a hat down over the infant’s eyes so the light doesn’t bother him. Nargizi with her kids has come up to these meadows to accompany her father-in-law and husband. They take the livestock out here to graze. It is Nargizi's duty to look after them and house them in the evening. She milks them, ties them up in the stable, makes some chechil cheese and kaimaghi (an Adjarian dairy product similar to sour cream), and churns the butter.

“I gave birth and milked the cows the next day. Who else would look after them?” Barefoot children covered in mud run noisily down the steps to play in the yard. The mother remains at home alone with the infant. “Thus we live,” she says through clenched teeth, as she casts her gaze upon the disheveled room. “Curse that day! It is better to die than get married.”

Satellite dishes arise like mysterious objects on century-old houses cast from the heritage of the past and the contours of the future, all into one dimension of time.

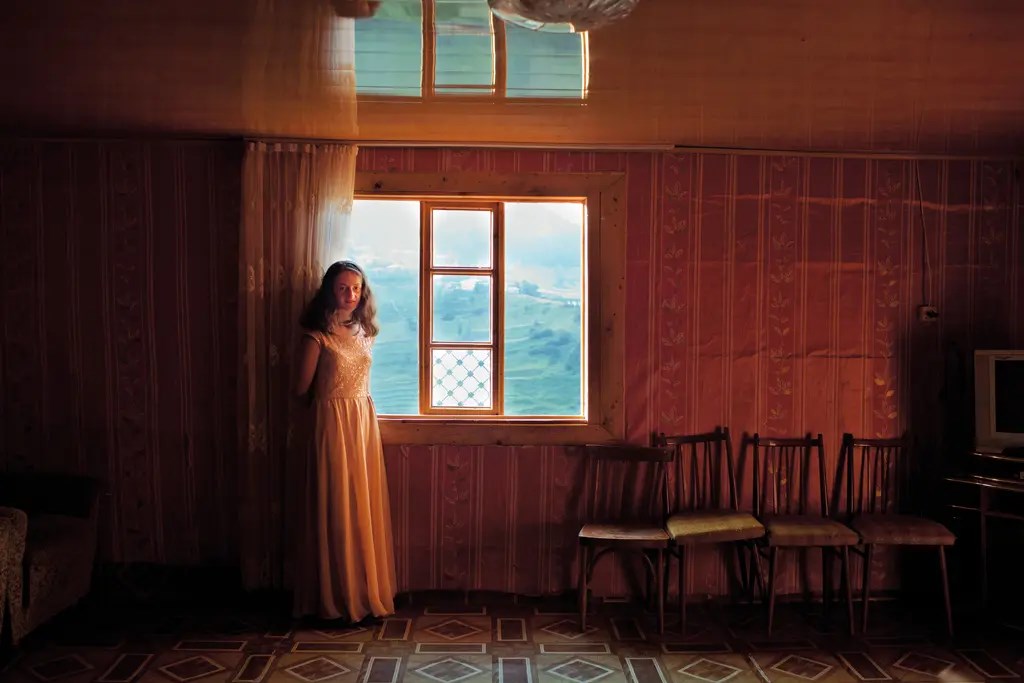

Slopes cloaked in mist appear from the window. It's as if the fog nestled in the valley is hiding the village from the outside world. There is no breeze stirring, otherwise, a white covering from the mountains would envelope the village after a single gust of wind.

In some Georgian ethnographic studies of the 20th century where Sergo Makalatia has described the customs of agricultural societies, marriage between families is an economic arrangement. Up until the 20th century in Mingrelia, children were engaged at 3-4 years of age. Free love stories among the mountain people appear more from the middle of the 20th century. These attempts at bucking the trend very seldom resulted in a happy finale.

...

There's been a racket on the Beshumi Hills since morning. Murveti sits on the balcony of a frayed wooden house and gazes out at her progeny. Girls and boys up to six-years-old are sliding in the mud on a homemade skateboard. The older ones are gearing-up for Beshumi Day, and the girls are combing each other's hair, and applying makeup to their eyes. The boys are sitting in cars with doors ajar, listening to remixes of Georgian folk music and smoking cigarettes.

Murveti has ten grandchildren and as she says, probably two times as many great-grandchildren. She is 78 years-old. She was twelve-years-old when her mother told her, “We must have you get married.” They had already selected the boy for her. The couple was soon engaged.

“I was in denial. I cried for days, but my parents won out over me. They gave me away.” Neither had the boy been asked his opinion on the matter.

“In our time, a girl was taken to a boy all covered-up, so he didn't know what was under those garments. My man also seemed ashamed like me. We were both wet behind the ears.” When Murveti turned 14, she went to live with her husband. She gave birth for the first time within a year.

Even her children were married-off in the same traditional manner. She chose the future spouses for them together with her husband.

“We asked their opinion. But not one of them opposed us,” she says. Murveti forced her one grandchild to marry. The fourteen-year-old girl wanted to continue her studies. Murveti called for all male relatives for the family gathering. “We threatened and cherished her from time to time. But there were many of us and we finally won her over.” The future son-in-law offered by the mediators was deemed as a profitable party to marry.

“We didn’t understand that the girl should choose the one to marry on her own. This was happenning 25 years ago,” Murveti says as she looks at the split palms of her hands, “We decided to do so with our incomprehensible wits. We married the girl by force.”

Today, forced marriage is punishable by law. If one member of the couple is a minor, the accused can face imprisonment of up to four years. Up until this time, girls that were married by force rarely returned to the home of their parents. Even in cases of physical violence, divorce was rare. Divorced women are a shameful blight on their families even today. The price of breaking a taboo for a woman is to be separated from her children and to stay in constant, silent, spiteful condemnation by those around her. At the same time, according to a rule established in the community, during a second marriage, the children are to remain with the father.

Teenage brides wearing colorful dresses and decorated with gold jewelry come to Beshumi Day with the bridal parties. All the future husbands there are adults. 14 and15-year-old boys are rarely forced into marriage by their parents these days. Such couples are basically only encountered in the older generation. Alternative to the forced marriage often is again marrying someone else. In order to get themselves out of an undesirable marriage, some girls run away from home with their boyfriends. For the time being, teenage girls can only fantasise about different life scenarios.

Married girls rarely go to school. Pregnant girls are embarrassed to attend the classes. They leave school in the fourth, fifth or sixth grade. From 2011-2013, more than 7,000 girls quit attending private and public schools before even completing the ninth grade in Georgia. Getting married before 18 years of age is prohibited by law in Georgia. Now minors do not have the right to marry – even if they have their parents' blessing. In fact, only a court can give such permission – and only in special circumstances. Yet, children start families even outside of marriage and these cases only become apparent during premature births. According to Georgia’s current legislation, adult sexual contact with a minor under the age of 17 is a crime and is punishable by up to four years in prison.

Only a few have heard about these laws in mountainous Adjara.

“Must I sit in prison after having married a woman fifteen-years-old?” Tamaz, a shepherd from Ghorjomi asks me in amazement. “Who has the right to sue me? Some policemen themselves have young women [that are] fifteen, or even fourteen years of age."

Dato and Tamari are a 25-year-old husband and wife. They became spouses through parental consent, but as they themselves say – it was out of love. “Not a single night have we gone to bed angry with each other,” Dato tells us as he looks at his wife. “We argue usually – I don't like it when she goes about with a head covering. I tell her that today, young people no longer cover their heads according to Islamic laws. She however, prefers to wear a scarf."

I look at the mountains on the way back from Ghorjomi. At this altitude, the horizon is nowhere to be seen, there are only chains of mountains all around. It's as if even time has a completely different resolve on the centuries-long relief. Dato and Tamar's story is a rare exception in these parts. A temptation to generalize arises through many similar stories and only the portrait of an oppressed young girl comes through in the general picture. Biographies have been lost in the statistics. For these young women, being obedient to traditions just means - accepting the reality. When they don't feel strong enough to fight for free choice, they say no to education and marry a boy who they simply prefer to others.

PHOTO: Daro Sulakauri

ეს სტატია მხოლოდ გამომწერებისთვისაა. შეიძინე შენთვის სასურველი პაკეტი