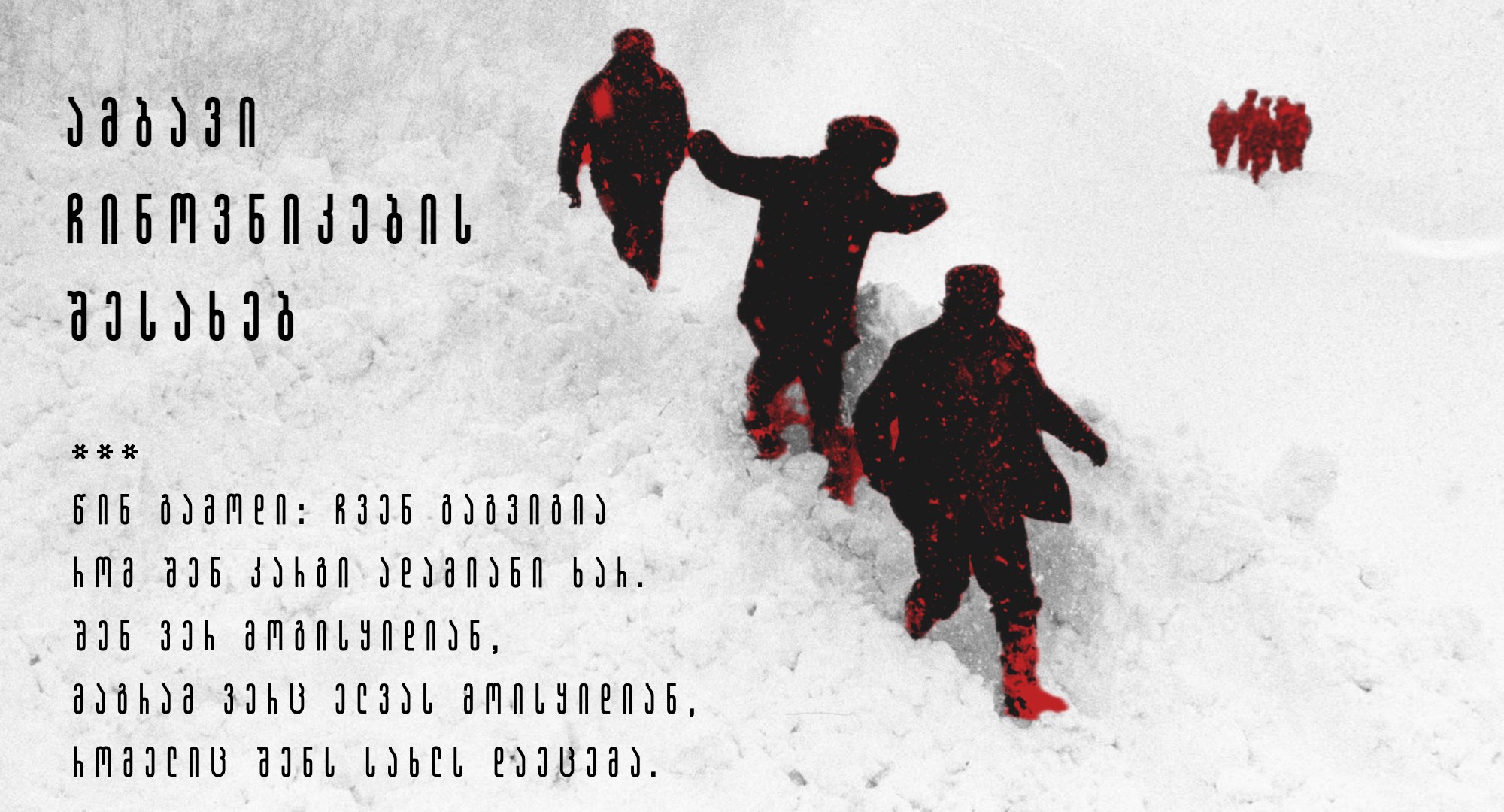

Reviled Man | Nino Lomadze

07.04.2025 | 15 Min to readA Story About Functionaries

Every day, I would run into that gloomy man, bald, with ruffled eyebrows. Sometimes he would furtively push open the shop door. Sometimes he would sneak into the entrance hall carrying a bag of groceries. He would always walk past you with quick steps, no hello. He lived in the building opposite ours, alone, in a one-room apartment. That’s how he was: colorless yet somehow abrasive. You would pass him by, perhaps not even noticing him, but an acrid taste would stick to your palate.

I was thirteen the first time I looked him in the face. An elderly neighbor had died, a real character of the neighborhood, and I went to the wake with my father. I was standing in the entrance hall with the men when I noticed that familiar bald head on the stairs. He was coming up slowly, head bowed. The neighbors began to whisper; those he passed looked away – men and women, everyone averted their eyes. He walked a circles around the casket and left the place without a word. A commotion followed; women sent quiet curses and hexes after his retreating back. We children, were confused. I turned to my father, 'But what did he do?' I asked. "He is a vile man, son," he told me.

That evening, he told us children, that an executioner lived in the apartment windows opposite ours. He had shot people with his own hands in those dark years, the period of Soviet political repressions in Georgia and Soviet countries from 1936 to 1938, when millions were executed or imprisoned during Stalin’s purges. In my childhood, there were few of them left. The system itself had disposed of them in due time; most were executed themselves or exiled. Only a few survived, but even they were doomed to such a miserable, wretched existence, my father said. "This city and country are small, and so, my dear, that’s how it goes – where there is no justice, the people will pass the verdict."

I memorized the story exactly like this. Word for word. I brought to life scenes from old video reels, Tbilisi in the 60s, and I filled in the characters and actions with those images. My uncle had told me this story, and a few weeks after that conversation, he had died.

...

My uncle was a chinovnik – a functionary. He held high governmental positions first during the Soviet period, then in independent Georgia. Both my uncle and my father were members of the Communist Party. My father served in lower positions; during Soviet times, he was a 'Partkom' charged with enforcing party ideology in institutions; later, he worked for several years as a Raikom, a district committee secretary. My grandmother – the mother of my mother – would often say with a laugh: "The only thing I asked my daughters was not to marry Communists, and look how they listened."

She was a Party member herself. "I am an accountant, my dear. They rewarded me with the Order of the Red Banner of Labor, you know… a participant in the Patriotic War, see?" she would inevitably tell anyone she just met. My grandmother loved her sons-in-law; "They truly turned out to be good men," she’d beam.

I first learned about the main men of my family in the yard when I was ten. After I got into a scuffle with a girl slightly older than me while playing dodgeball, she shouted, "Your father is a rotten Communist!" It was 1988; the national movement – an independent, anti-Soviet political movement in Georgia, founded by dissidents – was already gaining strength. I was fired up more by the word "Communist" than "rotten”.

"How could we little ones dare speak a word about politics? How would we dare?" my grandmother would recount her own childhood whenever I repeated slogans from the National Movement and asked her for explanations. "It’s dangerous. Someone might hear, my girl, someone might report on us. No good talking about politics at home. Do you understand what I’m telling you?"

My grandmother’s father had been a Menshevik before the Soviet occupation. As my grandmother’s sister used to tell us, he survived exile and execution on the condition of eternal silence and worked in the Education Department in a small provincial town of Western Georgia until old age. He was the only man in the district with a higher education, she said. "We lived in constant fear. Every night we waited for them to come and take Father away. How could we dare, how could we utter a sound about what the country was going through?"

After April 9th, in our "Diaries", we all already had carefully composed poems or sketches about Georgia’s independence. "Morrison or Kostava, huh? Who’s the cooler guy?" an older boy would laughingly ask the girls in the school corridor. The leaders of the independence movement in Georgia, the dissidents Zviad Gamsakhurdia and Merab Kostava, were already idols the size of rock stars. Their quotes were waved around everywhere. My aunt and her friends never missed a single rally. They were fervently reading and distributing dissident texts. I liked listening to them; their unconcealed anger would give me chills; their somehow unsullied faith was intoxicating.

Our family often threw big feasts. A few toasts, and the singers would gather, the song unfolding in polyphony. Then they would slam a hand on the table, and from the table, lengthened by boards borrowed from neighbors, someone would suddenly jump up, and a graceful dance would begin. Adults and children joined in; there would be a queue of those waiting to join others on the "stage" – a part of the dining room that had been hastily cleared of furniture.

Even in such self-forgetful revelry, in those very last years known as the Zastoi (Stagnation), a moment would still arrive when awkwardness swept through the room like the tolling of a bell, and we children were always the first to sense it. Something bitter said about politics, a clumsy or rough joke, would stretch the moment like a taut string. I would look at my father first. I would read the anxiety on his face and immediately grab the hand of the most trustworthy person – my little brother –, and we would huddle under the table or in some crevice hidden from sight. Political rifts were already splitting families and friendships.

"This Party has ruined you, stupefied you, enslaved you!" could be heard from the closed door of the big room.

I still remember how attentively I watched the facial expressions of the revelers and eavesdropped on their exchanges, trying to recognize the impending danger in time so I could run to my hiding place. I feared these clashes of adults more than demons and night ghosts; seeing them enraged, ready to spare no one, would make my heart rise to my throat.

I avoided talking to them until I was past thirty. I never asked my father or my uncle to tell me anything. And yet, my uncle was a storyteller without equal; people at the table would always listen breathlessly to his tales. We began talking in the last years of their lives, when curiosity overcame fear, and I finally decided to ask and to know even that which I might have wanted to forget immediately.

This fear was multiplied tenfold by Hannah Arendt’s 1963 book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, which I had read at thirty and immediately forced myself to forget, telling myself I wasn't ready to think about it yet.

"Naive ethical consciousness is constantly surprised by how staringly and warmly people who have committed acts of terrible violence treat members of their own group... The German soldier who killed innocent civilians was ready to sacrifice his life for his unit.' These words hung somewhere in the air above my head. 'Members of the group and family... caringly. Warmly..."

What did they have access to? What could they have prevented but didn't dare? What did they close their eyes to?

Whenever I thought about the main men of my family, I always needed to imagine the most radical examples to review in my mind the stories of executioners and those accused of murdering millions. I don’t know why, but this thought truly comforted me. Perhaps I knew that, at a minimum, it wasn't this, at a minimum, my ancestors' history was not like that?

These paragraphs, obviously, cannot close the history of my family in the twentieth century. I want this text to remain only about living with doubts, and not about the passion for justifying or exposing loved ones. Because I believe in the moment of alertness, only in this hesitation – a sober gaze and the open admission that on any tomorrow, even in the thirty-fourth year of post-Soviet existence, everything might change in a second. New knowledge might crumble our beliefs and perceptions into crumbs.

That is why I try to always think in the light of this question: How many citizens will be ready to unveil terrifying stories about our own parents, our sweet and fluffy grandparents? How many of us will say that we live in a house obtained because our ancestors fabricated one "harmless kompromat" on a neighbor for the KGB? How many of us from my generation can honestly tell our parents' stories? Not to idolize and take groundless pride in them, but to see them in the light of day? Neither to cast them out nor renounce them out of fear, but to carry their realities as still somehow manageable loads, to be able to deal with their circumstances, understand their motives, and comprehend their weaknesses.

"Until we are all gone, Daughter, this country cannot be saved," my father told me four or five years ago. "When our generation is washed away from the face of the earth, that’s when change will arrive." These words ran through me like an electric current, and at the same time, I remembered I wasn't hearing this for the first time. My friend's aunt had said the same to us: "When we die off, only then will this country straighten its back."

I thought then for the first time: They will really fade away slowly, slowly like this, without saying the main thing. They won't hide it, but they will choose not to speak up, and they will simply forget what they had heard or seen, decided and considered, believed and executed over the years – like an old, leaking bucket at the edge of the yard. They definitely will make sure to forget, yes, I fantasized, as a result of torturous and diligent exercise. And this would be the very last step of daily, emergency banishment and careful silencing, of rearranging things in the mind to suit oneself. Or, I tried to imagine what they would remember at all in a time when voices are muffled, screams are dammed up, and even the cracks for whispering and thinking are filled and sealed? In a time when borders are called the Iron Curtain.

Yes, I fantasized, because this was the only way to fill the voids they left me. Only in my imagination could I find the answers they didn't give, invent the stories they never told. Because even what I do know seems so carefully processed and rearranged. Or, perhaps it is not so at all. They didn't leave us documents proving their honesty and integrity either. They felt they would never need them. I thought then, too, these archives wouldn't open while they were still alive.

Today, when neither of them is with us anymore, I feel even more vividly that our relationship was doomed to eternal mistrust. No matter how much I want to believe in their sincerity, I can no longer fully trust my memory of them. Memories transform in time; the mind floats up only what reality dictates. I know, too, that this is an unconscious process.

The distance that appeared between us turned into a strange remoteness. Now I think that this distance turned out to be insurmountable for our relationship anyway, love could not shorten the distance. The distance became a burden; it became a shared load, and with the years, for my father and me, it turned into physical heaviness, into pain.

But maybe this is what my father had wanted? Maybe alertness had been his true gift? Maybe he had bequeathed me these doubts? Or was this fear-tinged hesitation passed down to me as genetic knowledge from my father, born during the Second World War?

I returned to Hannah Arendt over the years, slowly. First, I read interviews, then finally I returned to her report on the banality of evil and started reading it anew.

So, when Arendt went to Israel to attend the trial, she was preparing to meet a real monster, a man-eating beast. However, "Eichmann turned out to be neither a pervert nor a sadist; on the contrary, he was terrifyingly normal. This is a new type of criminal, where the perpetrator commits the crime without the ability to feel or realize that he is committing a crime."

Governance that stands on the preservation of its own power builds its strongest foundation on precisely such ignorance.

Eichmann, too, was created by such a system. Hitler’s Ministry of Propaganda toiled to train officials like him, while Himmler created complex mechanisms to manage the SS (Schutzstaffel).

Initially, they concocted and established new linguistic norms among their officials to mask the facts. One of these was "guaranteeing a pleasant death", by which they meant gas chambers. At the trial, Eichmann answered boldly that he considered inflicting unnecessary pain during "termination" unacceptable (precisely "inflicting unnecessary pain" and not the murder itself).

Thus appeared new professionals, "specialists in pleasant pain", who designed the gas chambers of Auschwitz, Majdanek, Belzec, Chełmno, Treblinka, and Sobibór. Through linguistic manipulations, they turned death camps into an economic issue. The collection of skeletons, sterilization, and the gassing of people were termed "medical procedures." Replacing gas chambers with vans in which naked people were killed by exhaust fumes was considered a successful solution to an economic problem. This "medical procedure" cost the Nazi government much less. Just as the Russian regime called the full-scale invasion of Ukraine's sovereign territory and the devastation of cities and villages a "special military operation".

Arendt writes that the SS treated their own employees with great caution because they believed that if a person did not like what they were doing, the work would suffer. Officials were protected from the torturous feelings of responsibility and guilt by "new laws" that untied their hands to commit crimes without pangs of conscience. "We understand that we ask of you the superhuman, that you will be ‘superhumanly antihuman,’" they instructed them, and Arendt thought that in the minds of people turned into murderers, only a filtered feeling and thought remained: that they were participating not in an evil and wicked deed, but simply in a difficult-to-execute, historic, grandiose, unique event.

For years now, I have had this habit: every week, I type my uncle's name into Google search. Now I ask ChatGPT the same and even task it with analyzing the context. I don’t know if he worried about this himself - what stories would remain, how the city would remember his history.

What will artificial intelligence pick out and how will it tell his story, in which list will it place him, to whose names will it chain him? I often think about this.

Some fifty years later, Elizabeth Minnich, drawing on Arendt, will offer us the reverse assumption: that there exists an evil of banality as well, which is committed by ignorance and ignorance alone. Jean Hatzfeld writes in Machete Season, where the executioners of the Rwandan genocide tell of their deeds, that people who do not think are capable of anything. The ignorant cannot foresee the consequences of their own decisions, because comprehending what has been done is possible only through the realization of responsibility. Slavoj Žižek (Robespierre: Virtue and Terror) writes that responsibility is not only the fulfillment of one's duty but also the realization of what that duty implies.

“Eichmann was not stupid,” wrote Jean Birnbaum in Le Monde. "He did not think at all – and it was precisely this that made him one of the greatest criminals of his era.”

"Talking to oneself is already judging," argued Arendt. A keen sense of conscience, opposing oneself is, in Arendt’s view, the cure for the banality of evil - thinking is everyday heroism.'

My father wouldn't tell stories about his father either. I only knew that my grandfather was white-mustached, gentle and warm, a caretaker of the family and a great defender of his kin. He died of a heart attack before I was born. I was already a student when I learned that during the Second World War, my grandfather served as the head of a German POW camp. What rank did he hold? I was always asking his children. Finally, I asked my father to help me collect his documents.

"As long as I am alive, don't do this, Daughter," he told me quietly. "Why?" I asked. "No documents and no requesting of files," his lips went completely pale. "As long as I am alive, don't do this. I beg you!"

Did my father really live with this fear until he was eighty?

I remember when I first came across this poem by Bertolt Brecht, I thought of my father again. I wanted to read it to him, but I never did. I wanted to use this poem to say that I was scared too.

Interrogation of the Good

Step forward: we hear

That you are a good man.

You cannot be bought, but the lightning

Which strikes the house, also

Cannot be bought.

You hold to what you said.

But what did you say?

You are honest, you say your opinion.

Which opinion?

You are brave.

Against whom?

You are wise.

For whom?

You do not consider your personal advantages.

Whose advantages do you consider then?

You are a good friend.

Are you also a good friend of the good people?

Hear us then: we know.

You are our enemy. This is why we shall

Now put you in front of a wall. But in consideration of your merits and good qualities

We shall put you in front of a good wall and shoot you

With a good bullet from a good gun and bury you

With a good shovel in the good earth.

Shame destroys the person; it kills the self. At such times, you feel with full intensity that you do not want to be who you are. The feeling of guilt is chained to behavior and still leaves a chance to distance oneself from it; it's just that this path again passes through painful confession and the realization of the mistake. Only the cyclical nature of crime, its repeated recurrence, makes realization impossible and gives birth to shame, which time cannot remove and which slowly becomes part of one's identity.

I think about this too: at which count of crime, which false testimony, bribery, falsification of evidence, intimidation, beating, blackmail does one cross the territory of crime and wrap people in the fire of shame? How many will there be in the Georgia of the 2020s from the new generation, who will have to sweep their own past under the rug, destroy it, cover the old with a new crime, just to be able to live in a temporary, illusory peace?

Just at the peak of Eichmann's career, two young peasants lived in Nazi Germany. Their story was described by Günther Weisenborn in the book Der lautlose Aufstand (1953). The peasants refuse service in the SS and are sentenced to death. In their final letter, the youths write to their families: "We prefer to die rather than act against our conscience and commit horrors. We know what the SS are doing." "They retained the ability to distinguish between good and bad and never suffered from pangs of conscience," writes Hannah Arendt.

What will you sacrifice for the truth? - What a huge question, how simultaneously mundane and philosophical. This is Maria Ressa's question, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate and Filipino journalist. Ressa poses this question in the introduction of her book, How to Stand Up to a Dictator. I realized I had never thought about the fact that truth is indeed a reward. And living by the truth is a luxury for which a price must undoubtedly, inevitably be paid.

Mzia Amaghlobeli and all prisoners of conscience imprisoned for almost a year by the Georgian Dream regime are paying the price for their great, vast, truly all-encompassing truth. They gave their days and nights, laughter with friends, and hugs with children and parents for the truth.

History knows that these are temporary designations, and Mzia Amaghlobeli’s administrative violation will never be termed a criminal offense. While “prisoners of conscience”, “false witnesses”, and “unjust judges” already have their own names.

One more thing that will remain as a shrill echo stretched into the infinity of the future will be the barely audible complaint of modern functionaries muttering from their offices:

“I can't do anything more. What do you ask of me?

How am I supposed to save...

I did everything, I said what I could.

I tried, I persuaded, you know how everything is decided here, what will my speaking up change?

It's impossible, you ask the impossible.

I can't change anyone's mind.

What I could do, with my mandate, status, position, and just being human...

How can I explain to you that everything is decided high up there at the power vertical? It's already approved there.

I cannot save anyone. I really can't do anything.”

"The story we tell ourselves to explain what we are doing is essentially a lie – the truth is outside, in our actions," writes Slavoj Žižek in his famous text On Violence. The truth crystallized in actions is visible. It stands and waits. And right there, nearby, new officials will be born again, who will still be appalled by their own powerlessness, yet will not be able to overcome the unquenchable thirst to be close to the prop-like brightness of symbols of power, to possess them – a thirst that will cover all moments of thought, depths of feeling, and humane space.

Finally, surrender will come, which looks more like faith, as if you were not defeated, but communed with the truth. As if this were truly and only this were your world, which slowly narrows in space, and finally, your daily life is locked between armored walls and windows, rows of armed security and cordons, and predetermined, established routes. Until the door is sealed, through which old friends will no longer enter, loved ones will not turn into old acquaintances, and finally, they too will disappear from sight.

And this will be the beginning of the life of another reviled man.

I haven't started collecting documents on my grandfather yet.

My father died a year and a half ago.