Several Episodes from the Life of a Harlot

21.07.2017 | 7 Min to readPolortz – (Armenian "Poghots" – street) a square, thoroughfare where people usually gather, an open area.

Polortzified – a disgraced, ignominious woman.

Ioseb Grishashvili, Urban Dictionary

"What are you working on?" the elderly lady asked me at National Archives of Georgia's visitors' desk.

"Brothels."

"I beg your pardon?"

"Brothels in Tbilisi at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century" I specify.

"One minute. Let me check if we have anything on that subject.

She dials a number on her cell phone.

"I wanted to ask you... hello? Who is this? Valiko? Where did I call exactly?"

She looks at the phone and puts it back to her ear.

"All right, I didn't mean to call you."

She hangs up and dials another number and talks to me at the same time:

"Thank God I didn't tell him I wanted brothels straight away; he would have been shocked indeed!"

They send me to the history department. I’m sitting in the Research Hall of the National Archives and poring over the catalogue: brothel, prostitution, bordello – nothing. One of the employees knocks on the glass partition and calls out to me. “Have a look at these” – she says, and passes me about thirty periodicals stacked on top of each other. I look through the magazines.

The pile of periodicals already checked gets bigger, and I worry whether I’ve missed something. Perhaps I turned two yellowing, stuck-together pages at once? Maybe I didn’t read something in enough detail? I try to connect the topics with each other: “Guidance notes on techniques for battling plague epidemics”. Isn’t it possible the brothels were closed down due to epidemics? Then I come across an “Enquiry on various persons and lists of houses”. This “lists of houses” makes me wonder… and suddenly: “On Prostitutes 1901”. I have found the end of the thread and start pulling it.

I order the documents and request the accelerated service. This means that, instead of lifeless digital copies, I receive piles of century-old and threadbare original papers. These originals carry information on the old city’s colors, textures, smells, dust and habits almost as if it were DNA.

I start with documents from 1849 – The Head of the Russian Army Corps stationed in the South Caucasus writes a letter to Major General Prince Vasily Bebutov: “We receive a significant number of low-ranking servicemen with venereal diseases in the military hospital and in order to avoid the spread of those diseases, it is my honor to ask if Your Excellence would be so kind as to issue an order to establish vigilant supervision of prostitutes in the city. Do you think it would be possible to check them as often as possible and then send the sick ones to the town hospital, as happens in all the major cities?” Just for your reference, at this point in time, the construction of the Opera House on Liberty Square had started 2 years ago, famous Georgian poet Nikoloz Baratashvili was dead, another great public figure Ilia Chavchavadze was 12 year old and the first Tbilisi horse-pulled tram would appear only 34 years later.

Bebutov copied the letter almost word for word and forwarded it to Military Governor of Tbilisi. He wrote the following at the end of the letter: “This is written by Aide-de-camp Kotsebu, please advice what measures should be taken.” The correspondence continued into 1851. While waiting for a reply, Kotsebu wrote to Bebutov again, asking for a response. That’s where I stop. It’s difficult to even make out symbols and letters in this florid handwriting, let alone the whole contents of the later. It seems this particular thread ends in a Gordian knot, and so I temporarily set this case aside and continue my research from 1901.

My next discovery is a pack of certificates issued by the Tbilisi City Women’s Hospital. The text of the certificates is the same on almost every certificate, with only the names changing. Some parts of the text that are illegible on one document are easy to make out on another and so I’m able piece the words together and come up with the whole text: “This certificate belongs to the brothel prostitute Pelagea Kurochkina (or) Varvara Rolchikova (or) Maria Gvaramadze (or) Elena Maraeva, who has been discharged on…” All the certificates are issued “for the attention of” a police officer. Several health certificates are attached to each one.

The format of the form genuinely surprises me:

"Health Certificate

Issued to the person engaged in prostitution...

------------------------------------------------------------"

The patient’s name and surname are the only words written in by hand. Her profession doesn’t need to be, since it’s already specified at the top of the document.

There are three columns on the certificate. The first two columns list the time and results of medical examinations and, of course, are filled in by a doctor. The third column gives the time and place of release and its contents vary according to what is written in the first two columns. If the doctor gives the patient a clean bill of health, the third column is filled in - not in the hospital, but in a police station. The document seems to be a sort of a visa or permit allowing its bearer to start working in another location, or at least this is my assumption. These documents registering these prostitutes, and the fact that they are jointly supervised by both doctors and the police, and even the fact that all the documents on brothels are preserved in the archives of the Gendarmerie, all indicate that the activities and movements of these women were tightly controlled.

I soon discover another document which allows me to say without any doubt, assumption and uncertainty, that prostitution was essentially legalized and regulated in the beginning of the 20th century.

This is a copy of a memo from the Ministry of Internal Affairs – a statement written in violet ink on two pages of lined paper - according to which, based on a decree of June 6, 1901, women working in brothels should be aged 21 or above. This restriction, however, does not apply to those women working in brothels prior this decree entering into force! I’m still in shock at the discovery I have made when the reading room assistant indicates that another file has arrived for me – a thick document in hard binding. This turns out to be an alphabetical index of women working in brothels. Do you remember those huge telephone books from the dial phone era? This index is exactly the same. Steps have been cut into the right-hand side of the pages and colored pink. The letters on each step have been colored with ink several times over. The pages are divided into vertical columns; the thickness of each column based on the amount of information that needs to be written there. It starts with numbers, then names, surnames, patronymic, age, religious confession, social origin, place of residence… I’m mostly interested in this last category and ignore the rest, but I’m left disappointed. Brothels are registered as places of residence everywhere, with no addresses mentioned at all. It simply says: “Brothel”…

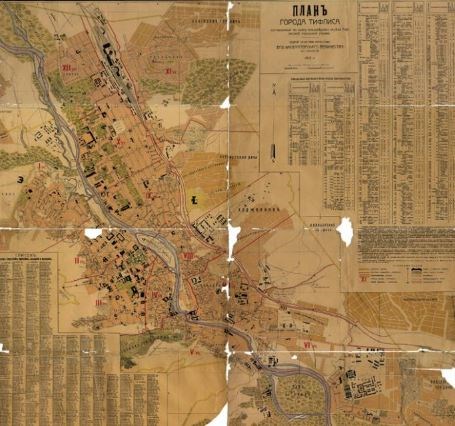

I haven’t told you yet why I started this research. The idea came to me last year when I went on a Tiflis Hamkari tour to the left bank of the Mtkvari River. We gathered on Heroes Square, crossed the bridge and followed the length of Aghmashenebeli Avenue. We then took a left at Marjanishvili Square and went down to Vorontsov Square via Tsinamdzghvrishvili Street. There, right at the corner of Tolstoy Street, there stands a red-brick house to the left. Its ground floor is actually on ground level (not elevated, as is often the case) and it has very beautiful skylights. We were told that this house is a former brothel. Those skylights actually belonged to the “working rooms” – a light in the window meant it was occupied. That very day, having heard the extraordinary history of an ordinary Tbilisi house, I suddenly wanted to find these former brothels and be able to place them on a map. I realized that I would be re-discovering a totally invisible layer of Tbilisi’s history – one that would be full of drama, passion and crime (I later confirmed the fact that these stories were full of shady goings-on while researching old newspapers)…

I haven’t told you yet why I started this research. The idea came to me last year when I went on a Tiflis Hamkari tour to the left bank of the Mtkvari River. We gathered on Heroes Square, crossed the bridge and followed the length of Aghmashenebeli Avenue. We then took a left at Marjanishvili Square and went down to Vorontsov Square via Tsinamdzghvrishvili Street. There, right at the corner of Tolstoy Street, there stands a red-brick house to the left. Its ground floor is actually on ground level (not elevated, as is often the case) and it has very beautiful skylights. We were told that this house is a former brothel. Those skylights actually belonged to the “working rooms” – a light in the window meant it was occupied. That very day, having heard the extraordinary history of an ordinary Tbilisi house, I suddenly wanted to find these former brothels and be able to place them on a map. I realized that I would be re-discovering a totally invisible layer of Tbilisi’s history – one that would be full of drama, passion and crime (I later confirmed the fact that these stories were full of shady goings-on while researching old newspapers)…

Now I sit in the Research Hall of the National Archives and wonder whether I can possible find the correct address of at least one former brothel to put on the map.

“You also have scanned files” the reading room assistant tells me, “Just enter the number into the computer, then signal to me and I’ll activate it from over here. Just push F5 and it will open.”

I go back to the computer. I feel hopeless – and since I had randomly selected the scanned materials, I’m looking through them without much enthusiasm.

Suddenly my heart skips a beat. Not figuratively, it literally skipped a beat as I see the words “List of prostitutes living at…” I open it up without reading the full title. The women’s names are grouped according to brothels. I look at it and can’t believe my eyes:

"At Eliarovsky street, house #9

At Eliarovsky street, house #6

At Eliarovsky street, house #7/2

At Eliarovsky street, house #1..."

This is a real jackpot: instead of just one address I have discovered a whole district of brothels - a red-light district in Old Tbilisi. The proof is right there in front of me, including a list of women that worked there. Now that I’ve found what I was looking for, I’m feeling a pang of sadness. Who were those women? Where did they come from? Where did they go to after the brothels were closed down? Take for example this woman, whose name is illegible to me: “—wife of Tbilisi resident” – how did she end up here? What’s been left of their stories except for these long lists written in very beautiful handwriting?

I’m going to continue my research, and in the meantime, you readers get ready for the Old Tbilisi brothel tour!

1

Tbilisi's Alexander Hospital on former Great Prince Street (now Uznadze Street) was founded in 1890 in honor of Emperor Alexander II. The hospital had 60 beds for women and 60 beds for men who were suffering from syphilis and other venereal diseases.

Source: Справочная книга по гор. Тифлису 1912 (Directory for the Cown of Tiflis, 1912)

2

1 Tsinamdzghvrishvili (former Elisabedi) Street

Former brothel

Source: Tiflis Hamkari

Newspaper “Droeba”, June 2, 1909

3

Starting in 1910, calls to close down the brothels of Tiflis started to appear in the press. Eliarov Street can no longer be seen on the Tbilisi city map of 1913, although it was included on a map of Tbilisi published at the beginning of the century. Judging by this photo, it must have been in Ortachala in the 5th Police District.

Source: National Library of the Parliament of Georgia, project titled "Digital Chronicler"; David Shughliashvili's photo collection.

Ortachala Street (formerly IV Nadikvari)

ეს სტატია მხოლოდ გამომწერებისთვისაა. შეიძინე შენთვის სასურველი პაკეტი