Three perspectives on Turkey's mass protests | Mikheil Gvadzabia

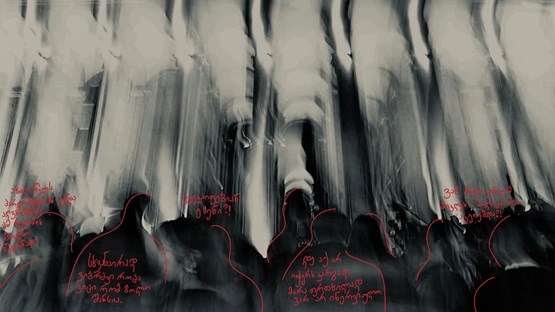

Reclaiming the streets after 12 years

At midday on March 19, during a spontaneously erupting protests, students at Istanbul University broke through a police cordon and rushed out of the campus. This was one of the first intense episodes of the protests unfolding in Turkey, which were soon described as the largest anti-government demonstrations since the 2013 Gezi Park protests in Istanbul.

Years later, on the morning of that same March 19, unrest once again erupted in Turkey—this time following the arrest of Istanbul’s opposition mayor, Ekrem İmamoğlu, during a police operation at his residence. İmamoğlu is one of the key figures in Turkey’s opposition and the main political rival of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Just days later, he was expected to be officially named the presidential candidate of his party, the Republican People’s Party (CHP), for the upcoming elections.

Many opposition-leaning citizens see this charismatic and solidly experienced politician as a symbol of hope for ending Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s 22-year rule (Prime Minister of Turkey from 2003 to 2014, and President from 2014 to the present).

Young people, in particular—those who have spent their entire adolescence knowing no president other than Erdoğan—place their hopes in İmamoğlu.

"We went to sleep in Turkey and woke up in Russia, " wrote Turkish online media outlet Fayn Studio on the morning of March 19.

Under Erdoğan’s rule, the persecution of political opponents, critical media, civil society, and academic circles is nothing new. However, the sudden arrest of his key political rival—just days before İmamoğlu was expected to be officially named a presidential candidate—clearly marks a new level in Erdoğan’s intolerance for any threat to his grip on power.

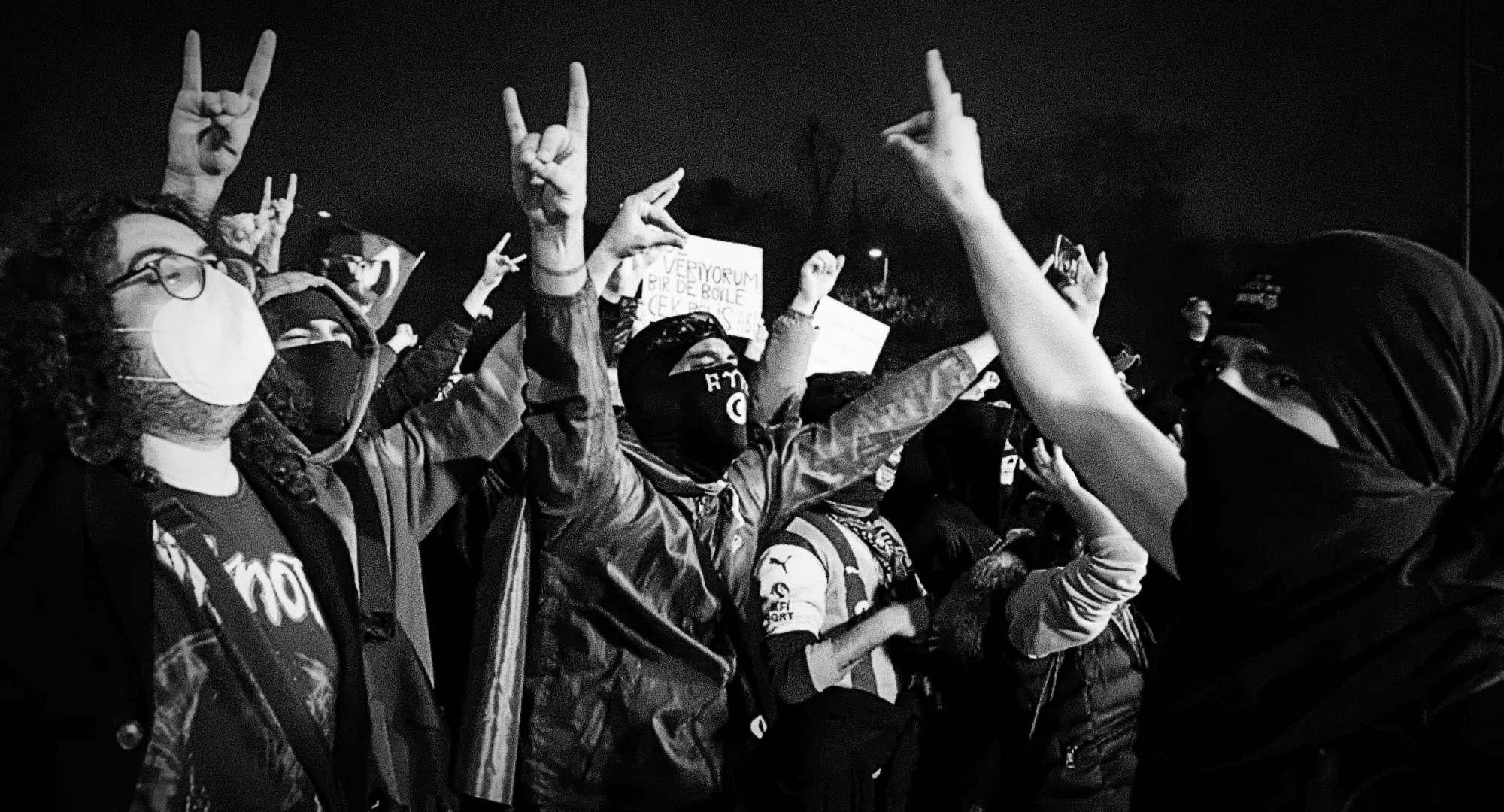

The public outrage sparked by İmamoğlu’s arrest quickly spread beyond Istanbul from the very first day. At the forefront of the demonstrations stood students—many of whom had never witnessed such powerful street protests before.

As a result, the student uprising has been widely described as carrying a dual significance: first, it clearly reflects the anger and dissatisfaction toward a government that has invested heavily in marginalizing and criminalizing street protests; On the other hand, it signaled a shift for the Republican People’s Party (CHP), which had mostly stayed away from street protests in recent years. Under growing pressure, especially from the youth, the party was compelled to step in and actively engage in organizing the demonstrations.

While the political and social-demographic makeup of the movement can be partially discerned, it’s still too early to draw definitive conclusions. What is clear, even to a casual observer, is that the movement is anything but homogeneous: From leftists to nationalists, the streets have brought together ideologically diverse groups who, despite their differences, have managed to stand united.

In the early days of the protests, We spoke with three participants in the protests in Turkey—two students and a recent graduate. Through their differing perspectives, we hope to capture the multilayered nature of the Turkish protest movement.

Arman

Arman realized the day after the Istanbul mayor’s arrest that he had become part of something far bigger than he could have imagined. He had seen protests on his university campus before—including those sparked by the rector's restrictions on student festivals—but never anything on this scale, and never so directly tied to the country’s everyday political reality.

“I understood that these people—students and others—weren’t going to disperse in a day. They hadn’t come out just to express their anger for a single day or night,” he said.

Students at the Middle East Technical University (ODTÜ) gathered on the very day İmamoğlu was detained. Arman, 22, is a student in the foreign language education department. He’s originally from Istanbul but moved to Ankara three years ago to continue his studies at one of Turkey’s most prestigious universities.

Unlike many of his peers involved in the recent demonstrations, Arman had some prior experience with activism.

“I think I was trained during [ODTÜ’s] Pride marches… Every march, there was a police attacking us,” he recalled.

For years, LGBT Pride marches were held without issue in Turkey's major cities, including Istanbul and Ankara. However, after the 2013 Gezi Park protests, increased state repression also targeted the LGBT community, one manifestation of which was the de facto ban on such events and the use of police violence.

Despite the ban, LGBT community members and their supporters continue to organize Pride events—both on the streets and in university campuses, including ODTÜ—at the risk of their freedom and health.

However, in recent days, especially during the night of March 20-21, the university saw an uprising of a different scale. The police met demonstrators at one of the campus exits and prevented them from leaving. The students, however, held their ground, building barricades from trash bins and resisting the police for hours, even as water cannon trucks entered the campus.

“They used plastic bullets, [tear] gas and pepper gas as well. I saw people shot by plastic bullets. One of my friends started bleeding from her head because of a plastic bullet,” Arman recalled.

ODTÜ is one of the most active hubs of protest in Ankara, but not the only one: protests also began at other universities, as well as in the streets of the city, including in the central Kızılay district.

“The arrest of İmamoğlu was like a breaking point for many people and I think they needed that, they were waiting for that, because… many terrible things are happening in every direction, from economy to human rights. and people have never had a chance to protest [with this scale]. But when the citizens saw that a big number of people showed up, more of them joined. When it’s crowded, you feel less scared, I guess. I believe we took power from each other.”

Republican People's Party (CHP), which the detained İmamoğlu represents, claims to be the continuation of the same-named party founded in 1923 by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Turkish Republic. In contrast to Erdoğan’s party, which has conservative, Islamist roots, the CHP is presented as secular and Kemalist. While the party currently declares a center-left, social-democratic orientation, it has historically been known for, and continues to exhibit, significant internal factional diversity, bringing together various ideological groups—from classic social democrats to right-wing nationalists.

Arman is a leftist and is particularly concerned about human rights, especially those of the LGBT community and migrants. His political views differ from those of the CHP: as he says, he is ‘more left-wing’ than the party and dislikes the presence of nationalist factions within it. Additionally, he believes that the CHP’s statements don’t always align with its actions. However, he emphasized that the reason for taking to the streets was not just the party or the arrest of the mayor of Istanbul:

“This is a matter of justice for me. For years, the same injustice has been happening to Kurds, Alevis, women, and queers... İmamoğlu’s arrest was a kind of excuse for me to come out and protest everything I’ve just listed.”

Arman is a transgender man living in a country whose government targets the queer community on every possible level — through hate-filled rhetoric, police violence, and, as human rights groups reported, new anti-LGBT legislation the authorities are seeking to pass. Among other things, the proposed law restricts gender transition and, in some cases, even punishes those seeking to transition with imprisonment.

“If you’re a transgender person in Turkey, it’s extremely hard to find a job — especially if you’re a woman. Renting a place is also difficult: I’ve almost never seen a trans person in Ankara who was able to rent an apartment with an official contract,” says Arman.

Arman’s family belongs to the Alevi religious minority — a community that continues to face persecution and discrimination in unitary Turkey, where “Sunni Islam, modernized and nationalist in form,” was established by Atatürk as a central pillar of Turkish identity. As a result, religious, cultural, and all other forms of pluralism have been treated as a problem, explains political analyst Elise Massicard in an interview with Le Monde.

These fundamental forms of marginalization are compounded by economic pressures: Arman and his friends live in a reality where, as journalist Murat Sevinç puts it, even the daily commute from home to university and a simple snack of tea and toast can be a financial burden for students.

Founded in 1956 in Ankara, the prestigious Middle East Technical University (ODTÜ) has long been known for its tradition of student — especially leftist — activism. Over its 68-year history, the university has seen numerous episodes of student demonstrations, clashes with police, and strikes. Among them was a nine-month-long strike in 1977, in which students and faculty members protested the appointment of Hasan Tan as rector, a figure closely aligned with nationalist circles and the ruling powers of the time. Tan eventually resigned, but according to various reports, two students were killed by gendarmerie forces and radical groups associated with Tan.

ODTÜ remains one of Turkey’s most politically active universities. Student societies and clubs continue to organize student festivals, Pride marches, and graduation ceremonies marked by bold political messages.

All of this unfolds despite the Erdoğan government’s increasing restrictions on political and social spaces — restrictions that many pay a price for. In 2018, four students were jailed for a month over a satirical banner mocking the president at a graduation ceremony and later had to personally apologize to Erdoğan. In 2019, 18 students and one professor were taken to court for participating in the campus Pride.

Still, the government has not managed to bring ODTÜ’s campus life under control. As soon as protests began this March, student groups immediately mobilized and divided responsibilities among themselves.

“In ODTÜ, we don’t have a leader… I think we have a natural distribution of responsibilities here: for example, we have a media society. They share videos and photos in a very professional way.

We also have an action committee, which unites the representatives from each student group of ODTÜ. I am there on behalf of the LGBT Solidarity group. We discuss when, where and what to do, whether it makes sense or not to take the front [at a specific location]... The other universities also act in coordination with ODTÜ,” Arman explained.

Both the student committee and the media society play a key role in ODTÜ’s resistance. It was they who circulated the footage of police cracking down on students on the night of March 21—videos that quickly went viral on social media. That same night, students from nearby universities rushed to the campus to support their peers.

“I try to be a bridge between people. There are so many WhatsApp groups, constant updates, tons of information… Don’t think managing all that is any easier than dealing with tear gas,” Arman jokes.

The students prepared for more than just tear gas—they anticipated a broad array of police tactics. At the beginning of the protests, they held a workshop where everyone shared what they knew—whether it was about the rights of detainees or strategies for maintaining unity during a demonstration.

‘We prepared saline solutions and distributed them among each other. Someone got masks, another person got glasses... There is solidarity. One pharmacist reached us out, offering to provide us with things that we might need during the protests,” Arman recounted.

In Erdoğan’s Turkey, university rectors are appointed directly by the President—a tool to control critical spaces within academia. ODTÜ’s rector is no exception. Yet every restriction imposed by the administration reignites the spirit of student resistance, along with the memory of past generations. Even those who graduated years ago remain connected to the university and continue to support current students in various ways.

“Last year, when we were protesting restrictions on the student festival, we camped outside the rectorate for a long time. Members of the older generations reached out to us — they supported us financially, physically… Some even gave open lectures,” Arman recalled.

The recent wave of rebellion is also shaped by the legacy of the 2013 protests, when police violence against those defending Gezi Park in central Istanbul sparked mass demonstrations across the country. In the aftermath, the government not only crushed the protests and severely punished some participants as a warning to others, but also launched a broader campaign to criminalize street protests as a legitimate form of dissent.

Still, Gezi’s legacy lives on — and serves as a source of inspiration for Arman and many of his peers, even though they were far from adulthood at the time.

“I swear, we must have mentioned the word Gezi at least 500 times yesterday. We constantly return to it — trying to understand what the participants did, checking archives... It's like we're learning it all over again, analyzing what happened back then,” he said.

Arman is happy to see mass protests returning to the streets. However, he says he’s also concerned by the movement’s diversity — much like the complexity of Turkish politics itself.

“For example, there are a lot of nationalists who can say things like, ‘We should lead the protests.’ Or some say, ‘Don’t throw rocks at the police!’ It really made me angry— they’re spraying us with pepper gas, hitting us with water cannons, and you’re saying not to throw rocks? I was really upset.”

But in the end, he tolerates the differences — because of the protest’s broader, common goal.

“In the end, people should understand that we are nothing if we don’t unite. I want everyone to see that big powers, government, capitalism, actually divide us. It’s not that you should hate Kurdish people or fear queer people; you’ve been made to believe that, you’ve been brainwashed. This is what I want to expose.”

Arman doesn’t expect a quick change — especially not for the groups he himself represents.

“It’s hard for me to imagine the future,” he says. But still, he doesn’t stop.

“Of course I’m scared. But it’s either now or never. When we’ve started such a massive movement, we have to keep going and expand it. I even get anxiety in crowds — sometimes, at house parties for example, I can barely move. But despite the fear or the anxiety, I try to focus on the public good; on the wellbeing of my community, of queer people, of my friends, of the people of Turkey. I remind myself why I’m here — and I try, at least, not to let fear and anxiety turn into cowardice.”

Sera

If her life were calmer, Sera says she would’ve never been interested in politics — “but now we no longer have that choice.”

That’s why she joined the protest in Adana, a city in southeastern Turkey, where she currently lives. Her very first protest came with its share of discomfort.

“On the first day, I was shy, quietly repeating the chants. But the next day — oh my God — I didn’t even know I could shout for that long!” she tells us, still surprised by herself.

In those first few days, it wasn’t just her voice that surprised her.

“For the first time in my life, I saw so many different people fighting for something together — LGBT people, right-wingers, leftists, Kurds, religious people, young people, kids, people from all sorts of cultural backgrounds…”

She also admitted the experience didn’t bring her unambiguous joy. At times, she felt uneasy—especially when some fellow protesters displayed nationalist symbols.

“I even found myself trying to walk a little further away from them,” she said. “But then I realized—that’s exactly what the government wants: polarization and alienation. So I chose to push through the discomfort.”

23-year-old Sera is in her final year at the Faculty of Education at Çukurova University in Adana. She wants to become an English teacher, but—like many others—she finds it hard to talk about the future.

“As a young person, as a young woman, and as a student, I feel lost,” says Sera—a sentiment that resonates with many of her peers.

According to a survey by the sociological research company KONDA conducted last year, 56% of Turkey’s citizens aged 15 to 24 say they would live abroad if given the chance. 71% are dissatisfied with the education they receive. And 39%—more women than men—say they have no hope for the future.

“The ruling party is always talking about how well we are doing, how we are developing, but we don't see it. We're not fools,” Sera said.

The currency crisis, inflation, and rising prices have hit Turkey’s major cities and the middle class hardest. This has directly impacted the already costly daily life of students: "For us, it's a luxury to sit in a café, go on vacation, watch a movie, or attend a concert."

Serra’s university isn’t known for political activism the way ODTÜ is. She had to go to her first protest alone, but later, her friends joined her:

“I had reasons to protest before, but I was afraid. Ekrem İmamoğlu's arrest was the last straw.”

“I am 23 years old, and I’ve never seen another president. Only him [Erdoğan]... You can’t criticize him, you can’t offer an alternative way. And it's not just us; this is happening within his own party as well,” she said.

The policies of the current government personally affected Serra: In 2021, Turkey withdrew from the Istanbul Convention on combating violence against women, following criticism from members of Erdoğan’s party about the document’s incompatibility with conservative and Islamic norms.

“Erdoğan always says that our laws are enough to protect women, but that’s not true, and we see that. The numbers of femicides and violence against women, in various forms, especially online, are increasing.

This change particularly pleased men. They were clearly asking, in a violent and threatening tone: Now who will protect you?!”

“They [the government] want a ‘traditional’ woman in this country. They don’t want anyone who thinks, speaks, acts, or expresses critical opinions… anyone who is an individual, a person.

These are the main reasons why I want change. Also, the illegitimate laws that [Erdoğan] brings in. And the question arises: Where are we living? This no longer resembles a republic, it’s more of a monarchy, and Erdoğan is like some kind of monarch, and a liar,” Sera concluded.

Sera comes from a religious family. For a long time, her political views were radically different from those of her parents and sister. However, as she says, the situation is gradually changing:

“Actually, my father stopped supporting Erdoğan about five years ago... He told me: “I must be blind not to see his mistakes; I must be blind not to see how he manipulates, how he lies, how he tries to win people's hearts with the religion card.”

However, regardless of what they think about Erdoğan, his parents are still expected to support the president, as both of them are public servants.

“For example, they still had to share his photos on social media. They are forced to. My father told me, every week they check ]individually, and if they find out that you haven't shared anything or shared less than others, it will lead to a conversation, which, in most cases, ends either with a ‘fine’ or being sent to a worse place for work,” Sera told us.

Sera is a voter of CHP – which the imprisoned mayor represents – emphasizing that it is the largest opposition party, and she will continue to vote for it in the future in order to change the government. However, she demands more from them.

“On the first day... I felt like we were celebrating something. They were singing songs. It felt like celebrating a victory that we hadn’t yet achieved. And if they don’t take action and just shout, ‘We’ll do this, we’ll do that’, this story won’t end in victory,” she said.

She has other fears as well: for example, what if İmamoğlu wins the next elections, but his current “inclusive and accepting” rhetoric turns out to be as false as Erdoğan’s was?

But she cannot imagine any other way than protest and also mentions the experience of other countries:

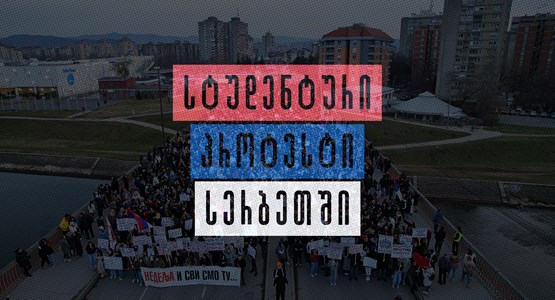

‘I haven’t studied it deeply, but from Instagram stories and news I was inspired by you, Georgians, and Serbs and I think, many others were inspired too. Perhaps this is one of the reasons we raised our voices, because we see how loudly people speak in other countries, and sometimes they even manage to change the situation.”

As a future teacher, she dreams of a high-quality, inclusive, and science-oriented education system, as well as a state “where we don’t just talk about the law, but actually see it in real life.”

Ege

Living in Istanbul’s historic Sultanahmet neighborhood, Ege is part of the future that Arman and Sera worry about. At 27, he holds a master’s degree in international politics, has studied in two other countries besides Turkey, and speaks three languages — yet he’s still struggling to find a job.

“This kind of disappointment is devastating. That’s why I try to find short-term, freelance jobs — in tourism, project management… I’m trying to become more financially independent, because there’s no other way I can cope with the current prices,” he said.

Ege complained that in Turkey the needs of young people are ignored—not just during elections, but all the time.

“We're seen as nothing more than statistics, just numbers. That’s why, during the protests, people shouted at the opposition leader [Özgür Özel]—they were demanding to be heard, to have their own place in this movement. They wanted a real chance to speak up and raise their voices.”

After Imamoglu’s arrest, protests outside Istanbul’s city hall grew louder—so did the frustration. At rallies where CHP leader Özgür Özel gave speeches, people shouted:

“Özgür, come down and breathe the pepper spray!”

“We came here to protest, not to attend a rally!”

Most of the yelling came from young people who had just clashed with police while Özel was speaking.

According to official statistics, Turkey’s unemployment rate is declining. But the same data showed that 2.48 million people have already given up on finding work altogether.

Before the protests, Ege had been aiming for a job in a government institution—he prefers not to name which one. But now, he worries that joining the demonstrations might have cost him that future.

“There are a lot of surveillance technologies, especially in the squares. That's why I decided to cover my face with a mask, so that I wouldn't be recognized by AI-based technology. I know that such technology is used.”

However, alongside the anxiety, there is also hope:

“I felt this when I was chanting secular slogans at the Istanbul Municipality, in the center of the conservative neighborhood [Fatih]. It was a very good way to go there and chant to declare that yes, we are here.”

Ege added that the current government does not represent the interests of people like him – “educated, secular individuals living in big cities”. His statement carries not only ideological weight but also an economic dimension:

“We feel the impact of the economic crisis much more severely than those in rural areas. If you live in the countryside, it usually means you own your home, have a small garden, and grow basic food for yourself… But if you live in a big city, you're automatically dependent on services, on store prices…”

In the major cities Ege referred to, CHP secured a convincing victory in last year’s local elections. This was accompanied by an unexpected breakthrough in several provinces long considered strongholds of the ruling party. As a result, for the first time in Erdoğan’s 22-year rule, his Justice and Development Party (AKP) was defeated in an election, coming in second after the CHP.

But now, with Erdoğan’s main rival, Ekrem İmamoğlu, behind bars, Ege feels a growing fear that meaningful change through elections might no longer be possible.

He believes it was precisely the fear of losing the right to choose that united people from different walks of life in Istanbul and other cities.

“I think Erdoğan’s dream is to build a system similar to Russia’s… I don’t believe he wants to abolish all political parties outright, but he does want to render them dysfunctional— to the point where people no longer feel any desire to take part in elections.”

Protest is nothing new for Ege. He is a graduate of Boğaziçi University — one of Turkey’s most prestigious educational institutions, known for its liberal values and its historic campus overlooking the Bosphorus. In 2021, President Erdoğan appointed a rector to the university by himself, sparking widespread protests from both students and faculty. Most of the demonstrations and performances took place on campus, but at times they spilled into the streets.

The state’s harsh response to the Boğaziçi protests is an example of how Erdoğan’s government treats any form of social dissent as a serious threat, even when the likelihood of it expanding is relatively low. Throughout 2021, the police repeatedly attacked student gatherings, arresting hundreds — some of whom spent months in prison.

At the time, Ege was in his final undergraduate year.

“[The arrival of Erdoğan’s appointed rector] directly influenced my decision to continue my studies abroad. Others also started applying to master’s programs, especially at universities in Europe,” Ege recalled.

Speaking about how Turkey reached the point of İmamoğlu’s arrest, Ege brings up the Erdoğan government’s policies toward the Kurds.

He speaks about the now-routine arrests of directly elected Kurdish mayors in the Kurdish-populated southeast during the second half of Erdoğan’s rule. The government accused all of them of ties to terrorism—namely, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK)—and replaced them with appointees sent from the center.

CHP has typically refrained from taking decisive action against this practice. This has been partly due to the factor of Kemalist nationalism and the party’s historically uneasy stance on the Kurdish issue. Compounding the problem is the Erdoğan government's constant conflation of much of the Kurdish political spectrum with terrorism, which has made many hesitant to publicly condemn the arrests.

Ege believes that even if the rest of the opposition had shown greater solidarity with the Kurds, a president wielding so much power still wouldn’t have made compromises. At the same time though, he noted that this general indifference has only given the government more room to maneuver.

“I think that secular citizens — myself included — were somehow indifferent to what was happening to the Kurds. And the government took advantage of that for its own interests... They started with the weakest link [the Kurds], marginalized them, and eventually achieved their goal [with İmamoğlu’s arrest],” says Ege.

Ege doesn’t shy away from stating that he feels a certain connection to nationalism — in the sense that the emergence of nation-states brought about democratic reforms. “That’s what I mean by it,” he said, “but we still need to be careful — because we need the votes of the Kurds and of others, too.”

According to him, the issue of the Kurds was also discussed during the protests at Boğaziçi University. Specifically, the question arose whether non-university issues, including the Kurdish topic, should be part of the protest agenda. He recalled that the majority chose to focus the protest on academic freedom, so as not to weaken public support for the students.

Ege is a CHP voter, but he doesn’t think the party's strategy is effective in all areas. In his opinion, the resistance after İmamoğlu’s arrest was largely driven by angry citizens, specifically young people.

“As I understand it, the opposition’s initial plan was to announce a one-time demonstration on Sunday, the day of the CHP primaries. However, the students forced the opposition leaders to extend the protest for seven days... That’s why I place the students at the center of this movement,” he added.

He is one of the critics within CHP who disagrees with the party's long-standing policy of avoiding street protests and focusing all resources on the electoral process:

“Their message was that if they had a good candidate, they would defeat Erdoğan. But now people realize it wasn’t that simple, because Erdoğan controls the judiciary, he holds the executive power, and he has a majority in the parliament. You're powerless.”

Ege believes that the tone of the opposition leader is now more “firm”, but he questions whether this is enough to bridge the gap between the opposition and the youth.

It’s difficult for him to confidently talk about his own future as well: He wants to live in Turkey, but without a stable job, it will be hard. He doesn't trust the evaluation system required to enter the public sector.

“They are looking for loyal types, which is why many incompetent people work in government agencies,” Ege said, with a thousand questions running through his mind:

Maybe he’ll eventually manage to get a job where he wants? Or maybe it's better to leave for a European Union country? What will happen if the government knows about his political views? Perhaps even this interview isn't safe?

We agree on full anonymity, just like with Sera and Arman. Finally, I ask him to share his dreams for the Turkey he wants:

“It’s a democratic Turkey. A Turkey without nepotism.”

______________________________

P.S. According to Turkey’s Ministry of the Interior, around 2,000 people were detained during just the first week of the protests, with over 300 — including students — placed in pretrial detention. Some of them remain behind bars.

Protests continue across the country, both from students and those organised by the CHP. Citizens are also expressing their dissent through other means, including boycotting companies linked to the government and refusing to consume their products.

We Recommend

Today’s Friday - New Agents Are…

12.06.2024