Renationalization and Independence: Reflections of April 9

16.06.2025 | 15 Min to readThe text is prepared based on the discussion held on 9th of April, 2025 at the Pilecki Institute, Berlin, organized by GZA - Georgisches Zentrum im Ausland (Georgian Center Abroad). The title of the event: "9th of April: The Day of Remembrance, Resistance and Liberation." The moderator of the event: Katie Sartania, PhD student at Humboldt University. Participants and speakers: Patryk Szostak, host of the Pilecki Institute. Giorgi Kakabadze, GZA co-founder, PhD student, and activist. Nino Lejava, director of the Belgrade office of Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung. Zaal Andronikashvili, publicist and literary scholar. Oliver Raisner, professor of Ilia State University.

...

Why does every significant historical date in the post-Soviet space, whether in scholarly discourse or public memory about decommunization and de-sovietization inevitably leads to discussions to renationalization? It often appears as though renationalization is perceived as the natural and the only way to resolve the processes of regaining independence. Concepts like decommunization, de-sovietization and renationalisation and independence, despite their frequent overlap, are not identical. Communism, Soviet ideology, and nationalism were often intertwined, yet the nature of nationalism varied. Was it a nationalism that facilitated liberation from Soviet/Russian influence? A nationalism that enabled self-determination? Was it civic, ethnic, religious, militarist, post-Soviet, or some hybrid of these?

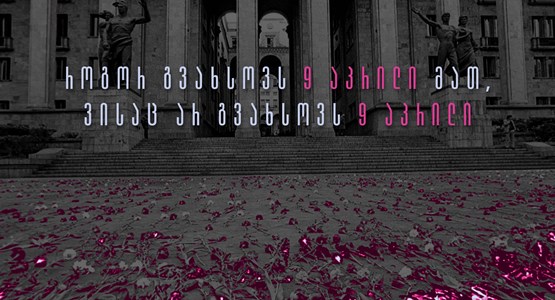

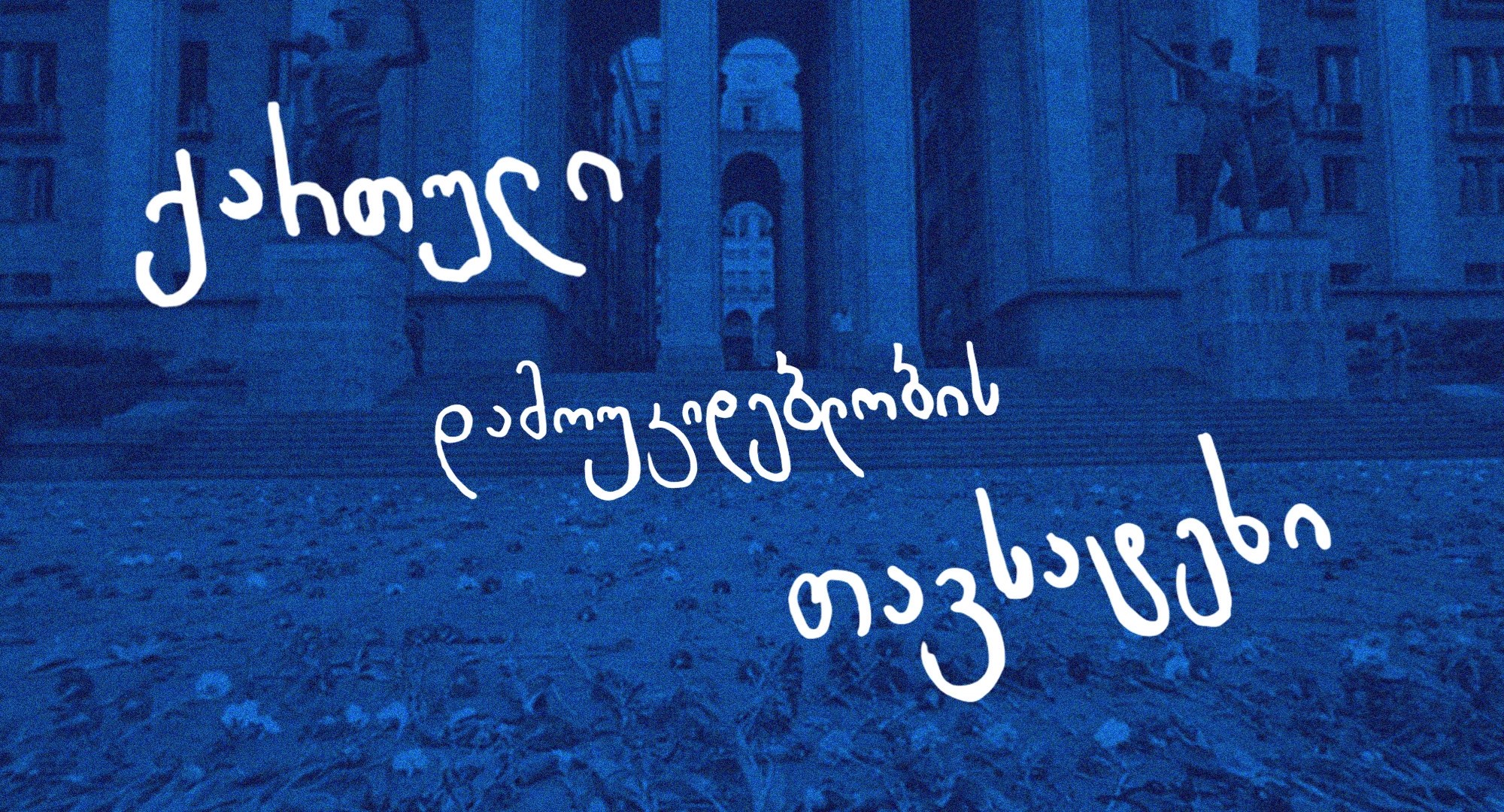

In the Georgian context, spring is particularly charged with nationalist symbolism, yet it also offers a potential for discussion and hope. April 9 marks both a day of mourning for the victims of the 1989 Soviet crackdown and a celebration of Georgia’s declaration of regained independence in 1991. Yet Georgia’s official Independence Day is celebrated on May 26.

Georgian political independence has always been framed in relation to separation from Russian dominance - whether from the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union, or, more recently, the Russian Federation. This historical struggle continues to shape the present in different ways. The First Democratic Republic of Georgia proclaimed independence on May 26, 1918, which later became the legal and political foundation for the Georgian Republic to reclaim its independence in 1991 based on the historical precedent.

Why was Georgia unable to transition smoothly from Soviet rule to a civic nation? These issues require deeper exploration and public engagement - especially as each passing year connects the pivotal dates of May 26, 1918; April 9 1989; and April 9, 1991 to the contemporary calendar.Yet the question remains - is a concept of independence merely legacy of the past, or a vision yet to be fully realized? On the warm evening of April 9th near to the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin, the Pilecki Institute, a Polish research institution, hosted an event organized by GZA - Georgisches Zentrum im Ausland (Georgian Center Abroad), to commemorate the events of April 9, 1989 and to discuss the above mentioned issues.

Initially, GZA was an informal group that emerged in Berlin following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022. Georgian students and residents in Berlin felt the need to speak up and engage in discussions on significant historical, political, and cultural issues. Currently, GZA is working to bridge the institutional gap in representing Georgia within broader historical, political and cultural discussions in Germany and beyond.

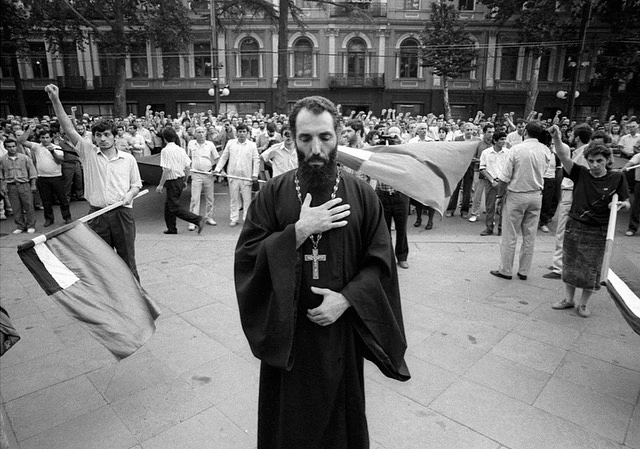

At the entrance, the first thing to catch the eye was the Georgian, Ukrainian, and Polish flags displayed side by side alongside the EU flag. On the wall over the flags, one could notice a big picture of a young man - Witold Pilecki, the institute, named after him, preserves the legacy of a courageous fighter who spent his life resisting both Nazi and Communist regimes. Pilecki infiltrated Auschwitz to document Nazi atrocities and organized a resistance movement within the camp. After escaping, he fought in the Warsaw Uprising (1944) but the 47 year old man was later executed by Poland’s communist authorities in 1948. Next to Witold Pilecki’s portrait, where the pictures from April 9 were exhibited, the hall was adorned with white and red tulips - a symbol of April 9, 1989, in Georgia - to honor the victims of the Soviet army.

Georgians familiar with the event aimed to present it to guests from a new perspective. In preparation, GZA members gathered after work at the institute, reflecting on how the event had been largely isolated from European history - despite its clear parallels to significant moments such as the East German uprising on June 17, 1953, the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, and the Prague Spring of 1968.

During discussions, GZA co-founder, PhD student, and activist Giorgi Kakabadze noted that while Gorbachev is widely regarded as a positive figure in Germany, April 9, 1989, still unfolded under his leadership. Tanks once again appeared on the streets of Tbilisi during the perestroika era - very much praised by the West.

It was unexpected, but symbolic when Patryk Szostak, host of the Pilecki Institute, recalled Polish President Lech Kaczyński’s 2008 warning that Russian aggression in Georgia could soon extend to Ukraine, the Baltic States, and ultimately Poland.

Szostak noted that April 9, 1989, was a pivotal moment when Soviet forces crushed a peaceful protest, killing over 20 demonstrators, mostly women and students. Yet, their sacrifice propelled Georgia’s push for independence, which was regained in 1991. He highlighted the Pilecki Institute’s mission to study historical totalitarianism and reflected on Polish-Georgian ties dating back to the early 20th century, when both nations struggled against Russian oppression. Though plans for a defensive federation failed due to Soviet aggression, Poland remained a strong advocate for Georgian independence. The commemoration emphasized two key messages: Wissen ist Macht - the power of knowledge - so history is never forgotten - and the need for perseverance, as Georgia reclaimed its independence despite repression.

Following the introductory remarks, a documentary, The Eye of the Storm: Soviet Georgia Revolution, made by American journalists Semion Smith and a photographer Richard Crabbe was screened. The documentary, filmed in April-May 1989 by two American journalists visiting Soviet Georgia as part of the US-USSR exchange program, is dedicated to conveying truth—It's a challenging task, but always worth an endeavour.

I was anxiously checking the news from Georgia, where for 132 days, ongoing protests have taken the capital, with its main avenue - Rustaveli blocked for several hours each night. Despite rain and frost, citizens persist, unwavering in their fight for justice, democracy, a free Georgia, human rights, and ultimately for a truly democratic Europe. Meanwhile, around 50 political prisoners remain behind bars on absurd charges, their trials closely followed thanks to tireless journalists and dedicated civil society representatives.

After the documentary concluded, we continued with a discussion featuring Nino Lejava, director of the Belgrade office of Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung. With decades of experience observing not only Georgia but also the broader South Caucasus region. Her perspective brought a deeply human dimension to the historical events. Then I asked Nino how does the documentary compare to her memories, not only of that day but of the broader historical context surrounding it? Given that memories are shaped by current political realities, how does April 9 continue to influence Georgia's collective mentality - does it primarily represent a national trauma, or does it serve as a source of empowerment in moments of vulnerability? Could it be both?

It was not an easy question, yet Nino, with quiet grace, shared her family story, recalling that over 50 years ago, her father studied at Humboldt University in Berlin. She reflected on how she tries to see Berlin through his eyes, back when the city was divided and under Soviet influence. She pointed out a crackdown scene in the documentary - one she had seen so many times that it almost felt like her own memory, even though she wasn’t there that night. However, she utilized an anthropological approach to distinguish real memories from those absorbed over time, relying on notes she wrote in her diary as a 13-year-old.

Early morning of April 9th her father entered her room, and she shouted one of the protest mottos, Sakartvelos Gaumarjos! (Long Live Georgia!). Father hushed her, explaining that young people had been killed, and she lowered her voice as she grasped the gravity of what had happened. Nino’s father, who worked at the university, would attend protests with his students to help protect them from potential danger. The days leading up to April 9 were filled with energy and sunlight - hopeful and bright. But after the tragic events, a deep sense of anger set in.

Since that time, Nino has carried a haunting memory of armed soldiers patrolling the streets, particularly of the so-called Бронетранспортёры (Armored combat transport vehicle). To this day, she feels anger and unease when she sees such military vehicles, even in memorial sites like Prague, where a Soviet tank painted pink by artist David Černý in 1991 stands. Frustration followed, a feeling of powerlessness, then physical restrictions, as a state of emergency was declared and Soviet forces remained stationed in the centre of Tbilisi.

On April 10, people gathered spontaneously in the courtyard of Tbilisi State University, a few kilometers away from the main scene. But when they saw the soldiers again, panic spread through the crowd. Nino’s mother offered shelter to some of the demonstrators, as her home was nearby. The prevailing sentiment was that April 9 would not be forgotten, it felt like a turning point in history.

A few months later, Nino visited her grandmother’s sister, who had collected all the newspapers from that day. She carefully cut out key pieces: poems, photos, which had a Mickey Mouse sticker on the outside of the cover, and pasted them into her diary, creating an unusual yet deeply personal documentation of the historical event.

In the light of her memories, Nino continued her analysis by emphasizing the historical duality of April 9. Even the invitation card for today’s event reflects this duality, linking the past to the present protests in Georgia. She highlighted the story of Nana Makharadze, a woman who became a symbol of April 9 - holding a black cloth, full of hope and expectations - which at the same time is widely believed to be the burgundy flag of the First Republic of Georgia. After the protest, she left to work as a labor migrant in Southern Europe, yet decades later, she found herself standing on the same spot, once again protesting against an unjust regime. April 9 embodies this same ambivalence: Georgians celebrate the restoration of statehood, yet the memory is burdened with grief for those who were killed and poisoned. It remains a tragic event that continues to be collectively reexperienced, with each generation interpreting it in its own way. She also spoke about Rustaveli Avenue, particularly the area surrounding the Parliament building, as a symbolic political space, an agora, for Georgia over the past four decades. This is why the ‘Rose Revolution’ of 2003 is significant, as its key events unfolded in the same location. Despite the devastation of April 9, bombing of the Parliament and the burning of buildings near Parliament in 1991-1992, and the ethnic conflicts that followed, the ‘Rose Revolution’ brought a positive narrative, turning the space into one of peaceful and democratic change.

Following Nino’s reply, I turned to publicist and a literary scholar Zaal Andronikashvili, to ask another entangled question: How do you perceive the dualism of the April 9 event, both as a tragedy marked by loss and as a victory in the struggle for independence? To what extent can these aspects be reconsidered or reinterpreted in historical narratives, and does the event have the potential to be redefined as an integral part of European history?

Zaal Andronikashvili described the 1991 declaration of independence as symbolic in terms of political rhetoric, as the memory of April 9, 1989, was inscribed within it. April 9, 1989, is seen as a foundational moment of Georgian independence, but the choice of this date is complex. While many nations celebrate their victories, Georgia chose a day of defeat and tragedy. However, from a Christian perspective, this defeat is also a triumph. Zviad Gamsakhurdia, later Georgia’s first president, revived a medieval Georgian paradigm of political theology centered on the figure of Saint George. As both martyr and victor, Saint George embodies a symbolic framework in which not only victory but also defeat can be interpreted as triumph — a core feature of medieval Georgian political theology.

Gamsakhurdia adapted this symbolic framework to April 9, drawing parallels in his speech from October 1988, where he contrasted two paths: the path of Barabbas and the path of Christ. The path of Barabbas represented a conventional political approach, associated with the Georgian Social Democrats who founded the First democratic Republic in 1918, which ceased to exist following the Soviet occupation in 1921. In contrast, the path of Christ was one of martyrdom - a sacrificial journey through which both the people and the land would mystically resurrect. For Gamsakhurdia, this was not a defeat, but a triumph. On a rhetorical level, April 9 and May 26 were framed in opposition. The First Republic, representing a democratic process, was tied to the path of Barabbas, and Gamsakhurdia suggested that God had taken Georgia’s freedom away. April 9, however, embodied the path of Christ - a path of suffering, sacrifice, and eventual resurrection. Andronikashvili argued that this interpretation of April 9, shaped by Gamsakhurdia, continues to influence Georgian discourse today. The religious significance of April 9 remains deeply embedded, and political martyrdom continues to define protests, where people stand in historically charged places. Regarding the reconsideration of April 9, Zaal emphasized that it not only can be reinterpreted but should be. He highlighted the need to address issues of rhetoric, political mythology, and theology in reconciling the narratives surrounding April 9 and May 26. Furthermore, he stressed the importance of crafting a new rhetorical framework for Georgia’s future.

Andronikashvili continued by exploring whether the April 9 event holds a distinct place in European history. It is often viewed in isolation, which narrows our perspective and prevents us from recognizing its connection to a broader shared European narrative. He argued that failing to integrate such events into a wider historical framework comes at a cost, as understanding history collectively could help prevent future wars and conflicts. Andronikashvili proposed revisiting April 9 within the framework of long durée, placing it in the broader trajectory of European history.

In the age of empires, Russia and Prussia rose to power - both involved in the division of Poland, both shaping the order of Eastern Europe. At the same time, Russia expanded its rule southward: to Crimea, the Caucasus, and even the Georgian kingdoms. The imperial order was not only territorial, but also epistemic. It determined what could be considered the "core" of Europe - and what could be considered the periphery, the antechamber, or the intermediate, gray zone.

When the empires collapsed in 1918, new states emerged - among them Poland and Georgia. Two old nations, two different visions of the future. In Georgia, under the most difficult conditions imaginable, a political project was realized that did not fit the usual patterns: a democratic republic, federally organized, social and secular, with minority rights, self-government, a 48-hour work week, and one of the most liberal constitutions of its time. It existed for only three years, but its blueprint points far beyond itself. He showed that democratic socialism was possible - without dictatorship, without the totalitarianism of the northern neighbor, which forcibly re-annexed Georgia in 1921.

The upheaval of 1989 did not begin in a single place, but in many countries. In Georgia, too, a broad popular movement for self-determination and democratic rights formed. The protests lasted weeks. On April 9, 1989, Soviet troops intervened violently: 21 people died - many suffocated by the gas used, others were beaten to death with sharpened spades. April 9 became for Georgia what June 17, 1953, was for the GDR - a day on which the system could no longer hide.

The call for freedom in Tbilisi was the same as in Berlin - the experience and hope for democracy were shared, but the aftermath was not. In Western Europe, 1989 was a success story: the Berlin Wall fell, Germany was reunited, the European Union expanded, and democracy appeared ascendant. However, in Eastern Europe, the path diverged. Georgia, Ukraine, Moldova, and other former Soviet republics emerged from the same democratic awakening, yet they were soon excluded from the EU’s enlargement process. Instead of political integration, a gray zone emerged - a space where Russia retained special rights to influence these regions. This gray zone has remained a battleground ever since, and the price of that exclusion is still being paid.

The full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the 2008 war in Georgia, and Russia’s ongoing hybrid warfare against Moldova, Romania, and the EU are part of this continued struggle. Andronikashvili argued that this confrontation did not begin with Putin - it may have started with the failed Soviet coup of August 1991, led by former KGB officials. What unfolded was an attempt to reverse the changes of that time, an effort Putin later encapsulated in his phrase about the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century.” His objective, Zaal suggested, is to undo the revolutions of 1989.

Georgia is not merely a marginal country in this story - it has played a central role in European events since the 18th century and remains a test case today. Its story raises the question of whether Europe is willing to take its own principles seriously. If the revolutions of 1989 began in Tbilisi as they did elsewhere, then the authoritarian backlash that follows should also be seen as a warning for Europe. Zaal’s key argument was that the struggle that started together must also be finished together. Not surprisingly, his remarks resonated with the audience, leading to the first applause of the discussion.

Finally, I turned to Professor Oliver Reisner from Ilia State University, teaching the social history of Georgia of the 19th century, and was invited to reflect on the significance of the April 9 event. The April 9 event has often been regarded as an isolated occurrence within Soviet history rather than as part of Europe’s broader narrative of resistance. How might it be contextualized alongside significant events such as the Hungarian Revolution (1956), the 1953 East German uprising, the Prague Spring (1968), and Poland’s Solidarity movement in the 1980s? Could it serve as a crucial link in the larger chain of European defiance against oppression? Furthermore, having witnessed these events unfold in Georgia, Reisner was asked to consider the future of April 9.

Professor Reisner started recalling his first visit to Georgia in October 1988, when he was invited by the Shota Rustaveli Institute of Georgian Literature at the Academy of Sciences from Göttingen University in West Germany. His visit coincided with the period of perestroika and glasnost, reforms that were already three years in the making yet failing to deliver Gorbachev’s intended changes. The middle ranks of the Communist Party resisted the reforms, blocking their implementation. Eduard Shevardnadze was seen as a reformer, but upon moving to Moscow as Minister of Foreign Affairs under Gorbachev, he was replaced in Georgia by Jumber Patiashvili - a hardliner who upheld the party's resistance to change. Moscow attempted to push reforms forward by promoting glasnost, allowing for media transparency to mobilize the population and overcome the stagnation imposed by the party’s middle ranks. During Reisner’s stay in Georgia from October 1, 1988, to January 3, 1989, protests were already underway. Gorbachev had initiated discussions about reforming the Soviet constitution, proposing the removal of the right of succession for Soviet Republics. This move sparked protests in Georgia in late 1988, which bore similarities to current demonstrations - marked by singing, dancing, heroism, and hunger strikes. Professor Reisner reminisced about his Georgian language teachers, Lela Gegushadze and Anna Abesadze, the latter a poet, who advised him to avoid attending protests. They drew parallels to the events of March 1956, suggesting that something similar could happen again. With glasnost, the inefficiencies of the Soviet system had become increasingly apparent, and ideological bankruptcy had already set in by the time Reisner arrived in Georgia. One pivotal moment occurred in September 1987: the canonization of Ilia Chavchavadze, a cultural hero of Georgia, on his 150th birthday. A figure shaped by Stalinist cultural indoctrination was redefined with the support of the Georgian Orthodox Church, shifting from a Soviet symbol to a national one. To Reisner, this transformation was a clear indication that the Soviet Union was ideologically collapsing.

“As a Western German,” Reisner reflected, “I was struck by how much emphasis was placed on the concept of ‘nation.’ Unlike in West Germany, where nationalism was rarely discussed, in Georgia, it was central.” However, he noted that one question remains largely unexplored: What kind of nationhood are we referring to? Georgia often references its First Democratic Republic, as though the Soviet period was a void, yet the impact of Soviet rule on Georgian society and its concept of nationhood remains largely unexamined. Reisner referenced [referred to Teresa Rakowska-Harmstone’s article from 1973 about] The Dialectics of Nationalism in the USSR The Polish-American political scientist differentiated between allowed expressions of cultural nationhood (nationality) and forbidden forms of a political (civic) nation. Since Stalin, the Soviet concept of nationhood was rooted in an ethno-cultural framework as integral part of the supranational political “Soviet people”. As perestroika progressed and central power weakened, matryoshka nationalism - a hierarchy of ethnically defined territorial units became instrumentalized by party elites seeking to maintain their informal control. Reisner argued that these topics have yet to be openly discussed in Georgia. April 9 remains a tragic event that set a precedent for political developments in the following decades. However, the evolution of an ethnocultural identity into a civic and politically engaged nation remains an ongoing challenge. Professor Reisner pointed out that Georgia’s cyclical political crises stem from these unresolved questions, and addressing them is essential for the new generation to shape the country’s future.

The transition in Eastern and Central Europe was negotiated between Solidarność Poland, the Baltic Republic Workers' Party, and political movements in Czechoslovakia. Unlike in Georgia, where political reliance has often been placed on individual figures rather than grassroots organization, the transition in these countries was shaped by structured, bottom-up self-organization.

During Georgia’s First Republic, the Menshevik-led Social Democratic Party fostered a tradition of self-governance, in contrast to the centralized Bolshevik model in Russia. This key difference underscores Georgia's historical dependence on personalities rather than collective organization. Solidarność, though banned in 1983, managed to survive through self-organized networks such as praca organiczna (organic work)[1]. In contrast, parts of Georgia’s elite historically collaborated with ruling powers, from the Georgian nobility in the Russian Empire to party officials in the 1980s, until the turning point of April 9.

Some Georgian historians, including Dimitri Shvelidze, argue that the country underwent a failed transition. A lack of national unity in resisting authoritarian rule became evident soon after independence was declared, and within six months of Zviad Gamsakhurdia’s election as president, Georgia plunged into civil war, the so-called Winter War of 1992–1993. This underlines how cultural identity alone is insufficient to build an integrated political foundation.

Professor Oliver Reisner observed that recent protests in Georgia indicate growing civic awareness, with the Muslim community also joining commemorations by laying flowers. Over the past few years, particularly in 2023, the ethnic dimension of protests has increasingly been replaced by civic elements, similar to Ukraine’s experience after the annexation of Crimea. When nations face serious challenges, civic identity tends to rise to the forefront. This shift offers hope for Georgia’s future, though critical questions remain. Reisner reminded the audience that Gori is not only known for one famous Georgian - Stalin - but also for Merab Mamardashvili, a philosopher. In 1990, Mamardashvili was confronted by nationalist figures who asked him whether he would choose truth or national identity. He refused to answer, affirming that a nation cannot exist without truth. Audience responded with applause. The discussion then opened for attendees' comments and questions.

The first question from the audience was directed to Nino Lejava, asking her to compare the ongoing protests in Serbia and Georgia and to discuss how the European Union has responded to each. The second question came from an attendee from Slovakia, who inquired about the number of victims of the April 9 events and what became known in the aftermath.

Nino Lejava explained that the struggle that began in Europe in 1989 can be described as Annus Mirabilis or Annus Horribilis, depending on the country’s experience. In the case of Serbia and the former Yugoslav states, conflicts and wars led to the isolation of Serbian society from the rest of Europe at that time. Today, a very different movement has emerged - one that is entirely non-hierarchical and, in some ways, apolitical. While this brings certain strengths, it also has its risks, because it keeps its distance from politicians of all colours. Comparing it to Georgia’s struggle reveals different contexts and approaches in how protesters act, yet both Serbs and Georgians share the same fundamental goal: to build a free, non-corrupt state based on the rule of law. Lejava emphasized that this remains the most crucial issue. Serbs are often being criticized for the absence of EU flags in its protests, unlike in Georgia, Ukraine, and sometimes Armenia. However, this is a deliberate choice made by Serbian students. Their primary struggle is to break free from corrupt elites and create a country where citizens can build their lives, raise their children, and be assured that democracy, the rule of law, and European values will be upheld.

After discussing politics and history, Zaal Andronikashvili captivated the audience with an anecdote that vividly captured both the key figures and the atmosphere of the Soviet era. In the documentary that was screened, a young protester, Irakli Tsereteli, one of the leaders of the movement, was seen speaking passionately to foreign reporters in 1989 about Georgia joining NATO. His enthusiasm was so intense that Zviad Gamsakhurdia and Merab Kostava, wanting him to slow down, assigned him the task of drafting a constitution, expecting it would keep him occupied for months. However, to their surprise, he returned just a few evenings later, proudly announcing that he had completed not one, but two drafts, and offered them the choice between the two.

The official part of the evening concluded shortly after 21:00, but the informal gathering, accompanied by Georgian wine, continued until midnight. The overall mood was a mix of confusion and hope.

After spending time speaking with guests and fellow Georgians, I left the Pilecki Institute around 11:30. The Brandenburg Gate is a place where people from around the world gather to organize protests and rallies, ensuring their voices are heard and seen on a global stage, among them - Georgians. But this evening was an exception. In front of the Brandenburg Gate groups of people were taking pictures, enjoying the pleasant evening, some playing loud music, while the warm spring evening in the heart of Europe carried a quiet promise - hope that people could unite and stand together again. Perhaps, every once in a while, we can learn from history and, just for a moment, challenge Aldous Huxley’s famous words: “That men do not learn very much from the lessons of history is the most important of all the lessons that history has to teach.”

For further insights on the topic, see:

- Zaal Andronikashvili: 2025, 9 May. Der Teufel in Moskau. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung.

- Oliver Reisner: Georgia and its new national movement. In: Egbert Jahn (ed.): Nationalism in Late and Post-Communist Europe. Vol. 2: Nationalism in the Nation States. Baden-Baden: Nomos 2009, pp. 240-266.

- Nino Lejava: Georgia’s Unfinished Search for Its Place in Europe.

- Eye of the Storm: Soviet Georgia Revolution.

text by: Katie Sartania, PhD student at Humboldt University

We Recommend