Today’s Friday - New Agents Are…

12.06.2024 | 16 Min to readForeign Agents Law in Russia

and other Complementary Tactics by Regime

Conversation with Sofia Gavrilova, postdoctoral researcher at the Leibniz Institute for Regional Geography and Olga Bronnikova, Associate Professor in Slavic Studies at the University Grenoble Alpes.

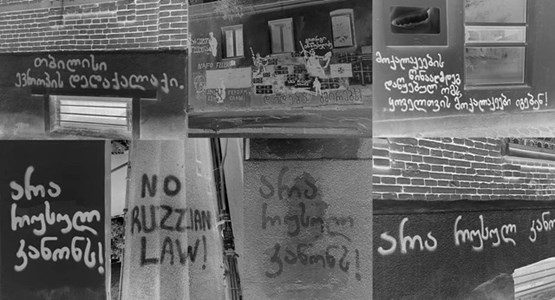

When Olga and Sofia returned to Tbilisi, Tbilisi was just beginning to get engulfed in April-May permanent demonstrations. Upon their arrival we first met each other on the evening of the first massive demonstration on Rustaveli avenue, just as people were gathering in front of the parliament building to protest the fact that after last year’s protests, the government broke its promise and it reintroduced the draft law on the Transparency of foreign Influence to be passed. What will happen? - on that evening all the prognosis was accumulated in this short and not very sharp question. It expressed various uncertainties and open-end questions. The only confident thought that we shared with Olga and Sofia was our firm belief: The people who will protest passing this law now, will not obey to it nor in the future; that this people are sure about the importance of civic values, about the importance of protecting freedom of expression; that our reaction to the one dimensional slogans like - “Never back to the USSR” or “Our Destination is Europe - our Home” - were multi-layered and well-thought, yet simple and clear.

All of the friends who attended that informal meeting of Indigo thought that this attitude of ours was rather optimistic. We even cheered ourselves up a little with that thought. Yet, Sofia and Olga had flashbacks from early 2010’s of Russia when the foreign Agents Law along with some other damaging legislative changes were adopted there. They had associations with the events from their past and we had curiosity: how did it go for them? Was it a slow process or all went shockingly fast?

We gathered again to reflect on the similar topics and then we together finalised this text too, which is no means the attempt to find parallels with Georgian and Russian civil societies or with the hardships of adopting the law. We did not record this conversation to compare neither the forms of the protests, intensities of them or deficit even, nor the tactics our governments chose.

We try to learn about each other in order to let ourselves better evaluate our own individual path; and challenges.

Who stands were; facing what.

Tamar: Can you recall the steps towards extreme authoritarianism in Russia. When did you start noticing this downfall of basic freedoms of citizens?

Olga: I noticed that things were changing in Russia when my parents started changing. First it seemed ok, even though I still could not understand what was there that my father disliked in my activities; I’ve always admired his path. I’ve always been fascinated with how he was engaged in the pro-democratic protest at the end of the USSR. I also knew that his activism irritated his own father - the dedicated Stalinist - who believed that his son deserved to be condemned since he participated in the destruction of their “glorious country.” However, my father went ahead and along with his colleagues from the Mathematics Department of the Leningrad University with a campus in Peterhof, created a small group of pro-democracy activists. Then, after the USSR, he was engaged in the creation of the new economic field and he even created the first bank in Peterhof, which he was very proud of.

[Evgeniy Isaev/Flickr]

[Evgeniy Isaev/Flickr]

Then, in 2011-2012, my parents started to ask questions like why I decided to support Russian activists in exile; While living in France and while doing my academic research at the Grenoble University, why I was involved in creating this liberal and also leftist medium of Russian immigrants abroad. But I just could not help it, because that’s when I discovered other Russian immigrants who think like “us”. Same feeling was noticeable among my friends who still lived in Russia. They went to the anti-government protests in 2011-2012 and they were surprised that they saw so many like-minded people; as if ‘whole other Russia’ opened up in front of their eyes. It became so visible and so powerful that I decided to write about this.

We also created groups for Russians who needed to immigrate for political reasons, and who wanted to ask for asylum in France. I participated in one such group and helped three anti-fascist activists from Russia after the Khimki movement to flee the country. These actions for me were a recreation of links and relations with Russia. Also, the hope was born that I could change something in Russia even from a distance. It was important for activating my agency – finally, I was becoming an actor, I was doing something and I was seeing the results. That’s why I said it was the beginning of my political life.

But my parents doubted all these. They could not understand my motifs. But these questions were ok, because we could at least engage ourselves in a dialogue, I could place my answers and motifs. But then 2014 came and my parents supported the annexation of Crimea. And that became the turning point for me. Slowly but surely then they supported the beginning of war in Ukraine and generally they became obsessed with the topic of Ukraine; also with the topic of LGBTQ in Russia. I understood that now I was having the same sort of conflict with my parents as my father had with his dad. It was the same with my brother too. He was constantly in conflict on political subjects with our parents. It was a very personal tragedy for me, a very deep trauma and I understood that even the person like my father changed.

Tamar: How is it now?

Olga: We never discuss the political situation in Russia or in Ukraine, we just talk about family affairs. I remember well that when the full-scale invasion started, we still touched the topic and I said something like, sorry, but it is “pizdets” (we are in deep shit). And my father told me there are things far more tragic than war. I asked, name it then. He told me, you will understand one day.

Sofia: I also think that political activism for me also starts with my family. My mom - back in Soviet days - would reprint samizdat literature and spread it out; my father would translate censored films from English into Russian and also distribute them in a secretive manner. Actually it was my father who took me to the “Memorial” when I was 16 so I would volunteer for their research projects. One of them was about the Soviet repressions in the regions – about the regionalization of the memory and mapping Gulag camps. However, I can’t be sure that all these actions of mine were fully conscious, maybe I just had been reacting in the way that seemed right to me.

Then my true political act followed. In 2007-2008 when pro-Putin and pro-Medvedev youth organization Nashi – something like face-lifted Soviet pioneers - conducted a demonstration in front of Moscow State University Main Building. I was studying there at this time. I saw how the demonstrators carried portraits of Irina Khamada and Mikheil Khodorkovsky as the enemies of the country. My boyfriend and I went up to them and started talking, but they called the police and we were taken to the police station. That was the first conscious political involvement for me. During those protests mentioned by Olga of 2011-2012 I still lived in Moscow, doing my Masters degree at the Moscow School of Photography and I was very intensely involved in the demonstrations thanks to my professor who taught students how to be political through the mediums of art and writing.

I left the country in 2013 for Oxford to do my second PhD with the financial scholarship created by Mikheil Khodorkovsky before he was sent to jail. So my major political awakening - linked to the Crimea case - happened while I was already away, the fundamentals though were the massive protests of 2011-2012. Photos in my Facebook memory remind me about these massive protests. Whole boulevard ring was closed with no cars and people were multiplying and we had all the flags and transparents. Yes, that was possible back then, but I can’t say that it actually was beneficial for the protest culture to be evolved.

Moscow. 2012. [Sofia Gavrilova's personal archive]

Moscow. 2012. [Sofia Gavrilova's personal archive]

Tamar: But how could it not?

Sofia: When the government started to implement more authoritarian rules, it became impossible for that protest spirit to thrive. The reactions the government developed towards the protests deteriorated after the annexation of Crimea. Although, even in 2017-2018, we still had massive protests in Russia. Criminal records about the people were of course opened, but still the protest scene by no means was as sterile as it is now.

The other crucial moment was when the government started to pay attention to the art-scene, because I remember first protest gallery Zhyr (Жир галерея) operating at Vinzavod (former factories in the central Moscow transformed into the modern arts center). We were doing protest exhibitions, there was even a festival of protest art, MediaUdar. I myself had a series of photos mainly, and then of course there were Pussy Riots. Pussy Riot's case was the very first and very loud persecution of artists; also shocking; and also very quick. I mean that art-scene was targeted by the government in a blink of an eye and that’s why it was hard to believe that it was happening; but then, come on, we see, Zhenya Berkovich is in jail too.

[Denis Bochkarev]

[Denis Bochkarev]

And then self-censorship followed. I tried to maintain a lifestyle in between two countries, doing that, also, intellectually. That’s why I used to teach seminars in Russia until 2018-2019. I used to work on the topics of the Russian museums for my PHD thesis. I remember, a colleague of mine approached me once and invited me to teach at the newly opened Geographical Department. “Sonia, what will it take for you to come back to Russia and work with us?” - was the question. I said, ok, give me the laboratory where I can work on the history of repressions and terror and I will need two other people in my team. “You know, I can’t do that, this is impossible, we should not be talking about this,” - was the answer adding: “I know very clear boundaries of topics we should not touch.”

This was another awakening moment for me and a final, very important change when even intellectual collaboration became impossible for so many reasons. On the other hand I don’t buy the narrative that we can't even talk with Russian scientists and I think we should all think about solutions, theoretical solutions to find.

Olga: I think it was about the same period when we started a scientific-sociological project about Internet and Internet freedom in Russia. We conducted interviews with different web and media professionals either located in Russia or emigrated abroad. And I remember one journalist from Media-Zone in Moscow explained to us the very complicated model of how they published things: What they could say, how they could say it and when; how not to use particular words and all the other very complicated things…It was then that I realized the depth of the practices of censorship and self-censorship in Russia. I think the journalists understood this even before Meduza went abroad; after the Lenta story.

Sofia: I’d like to go back to the initial question of Tamar’s about the reasons for changing the protest culture in Russia. We all remember how the protests of 2011-2012 were massive and also innovative. People would walk - as a protest showing that it is not a protest rally or demonstration, here, we are just walking. Also there were protests with the white ring, because the symbol of the protest was this white stripe and so people would make a chain around the garden ring with just holding hands. But then the government changed the law on protests.

Olga: Exactly, that’s when it started and it was 2012-2013, when they changed the law on protests. This law was primarily aimed at protest organizers. But in a situation where demonstrators went on non-declared demonstrations, without organizers, the responsibility fell on all participants. I remember many jokes online at the time: participants in non-declared demonstrations - walking protest - would reply to police officers that they'd just gone out to get some bread. And then it was followed with the law on the foreign agents, the first version approved in 2012 and then it was enlarged. And all other terrible laws.

Sofia: Since the system banned group protests without approval, people found some innovative ways to protest including these walks. And then it triggered the “Occupy Abay”, which was dispersed in very violent and super aggressive ways. I can also recall that during the first phases, yes, people were taken to the police stations, but they were not beaten up. But then they started to beat up detainees. The police started to be far more radical and physical in response.

Olga: Yes, repressions became tangible. Especially after the sixth of May, 2012. It was actually the biggest demonstration in Moscow when police arrested a lot of people. And I think back then another culture started to develop in modern-day Russia: the culture of supporting political prisoners. However when it was the case of Khodorkovsky, people did not express the same reaction, because after the sixth of May a lot of activists and also a lot of regular citizens engaged in politics discovered this tendency of repression.

Sofia: Maybe because he was not put in prison because of political reasons. The reason was economical and there was also a murder case, the rumors and that’s why. But we forgot Nemtsov. Death of Nemtsov also changed the atmosphere.

Olga: But the sixth of May, 2012 was even more important for this culture of supporting the political prisoners. Of course it existed before, but only in the closed community, for instance anti-Fascist activists were engaged in such actions already. And then people started to write letters to prisoners, they started to organize help for them, material help. They also started to talk about this, and to write about this, also using social media and professional media for that.

Sofia: One of the forms of mobilization was to participate in the Telegram channels. I'm still in these telegram groups. divided by the region, the districts, in Moscow to bring some basic stuff for those who have been held in the police. So, you would say, okay, I'm free, I am in this district, I can buy tooth-brushes, some hygienic products, some food and bring these stuff to the police station and then you would get reimbursed, but lots of people never asked for reimbursement.

Olga: But for supporting prisoners, those organizing from abroad would collect money and would send it to Russia to support people who were supporting people in jail.

Sofia: I remember that I was doing that with my toddler daughter still in the trolley because I lived very close to one of the police stations and I knew that the policemen wouldn't have guts to refuse me as a young mom to deliver a package to the prisoner.

Actually, once a month, Russians in exile in Leipzig still gather to send letters to the prisoners in Russian jails. It is electronic and it is very cheap. people do that even from Tbilisi. Of course, these letters go through censorship, but at least their loneliness is somehow eased up, and you can also prepay their response. I know some who had spent months and years talking to the prisoners. And I also remember that the telegram channel was created in which the moderators would match political prisoners with volunteer letter-writers to make sure that all the prisoners received mail.

Olga: To me it is a very good example of transfer from social and charity activism into political activism. In our joint article with Sofia[1], we talk about Russian political grammar grounded in this ‘theory of small deeds’ – when you substitute political action with doing something small; small but socially active. Today this kind of culture is criticized. Some political activists and also Ukrainian activists say that you were only engaged in this ‘small deeds’ culture, when we were protesting; and now we are invaded because of you; because you were engaged only in that. But Sofia, you mentioned a precise example where these small deeds can be transferred to the competences and political activism.

Sofia: I want us to remember this chronology too. If we are talking about 2012 - back then the protest culture was very loud and not only the ‘small deeds’; the culture which triggered ‘the rally of millions’ which then resulted in the ‘Occupy Abay’, where people were loud, where people took over the street and sat there an example of a very loud and of a very physical protest. Our art-classes were relocated from the school buildings to that square, near the Abay monument. And we would be discussing the protest culture, drawing parallels with different countries. People were volunteering and bringing food. There even was a guy who brought a cow from the village for the fresh milk. “Occupy Abay” lasted for five days and then it ended because of the ‘legal complaints by the neighbors’ that gave justification to the police – as if they needed one – to clear the area. People were arrested and taken to the police stations, but they were not beaten up at least to the extent that we started to see later and later.

[James Hill/The New York Times]

[James Hill/The New York Times]

Olga: So Ukrainians will tell you: you see, for Russians the protest lasted for five days, and then they stopped. If we look at the Maidan, in 2013, It started precisely at the moment when students were beaten up by the police, that’s when it got radicalised. These people could not just go home and get back to normal when youngsters were beaten up on the street. They just could not.

Sofia: And how would you explain it then, Olga?

Olga: That it did not happen in Moscow? Half-jokingly, by our ‘culture of small deeds’.

Sofia: As if it is in the genes of Russians to frame ourselves with this minimal form of activism.

Tamar: We are joking a bit here, but seriously, what can be the reasons for ending the protest spirit?

Olga: In Ukraine it was the first time that the students were treated that violently, and the whole society was shocked - how can you do this to our children! Anger was poured out; and in Russia, it was not really the first case of beating up demonstrators.

Sofia: Maybe I'm bringing geography here for the wrong reasons, but Russian geography has also something to do with a specific form of starting the protest and then failing. For instance, we should not forget that the protests were not happening only in Moscow and in Saint Petersburg, although there is this underlying feeling – at least for myself – that with a country of this size it is hard to change something in one place. So even though the protests were happening in other places, the reasons for them were different – they had national and also they had their specific regional and local agenda. For instance, they would rally in the regions in support of Navalny, but also for some specific local issues. So, for me there is always this rhetorical question - when will your protesting voice reach Khabarovsk from Moscow? There people are awake when it is already night in Moscow... I think this geographical circumstance also plays its role in immobilization.

Olga: Not just geographical circumstance, but also indifference. A French colleague of mine, Perrine Poupin, used to research regional protest groups in Russia. And she had this case of protests up in the Northern part of Russia, in Shies[1] . People protested there for two years about their local, regional issue against the “Moscow’s trash” (construction of a landfill). They organized a camp and stayed out there during the winter seasons too; and we can imagine how severe winter months can be in the Arkhangelsk region where weather is not the same as in Moscow. But their protest was never considered on the same level as the demonstrations in Moscow. he major problem for the protest movements in Russia is that the activists from Moscow and also from Saint Petersburg, were very concentrated on themselves. What is happening in the capital, what is happening in Occupy Abay – that’s big, but really, no interest in what is happening in other regions of Russia.

[Matthew Luxmoore/Al Jazeera]

[Matthew Luxmoore/Al Jazeera]

Sofia: So yes, it's also about the geography. Everything is Moscow-centered, right, Olga? Which means that we never protested in Moscow for any regional problem.

Tamar: We discussed the changes in the law about protests and we also discussed how the loud protests were gradually diminished to become only the ‘small deeds movement’. How did the Foreign Agents Law contribute to this process and what were the very first consequences?

Olga: It was first introduced in Russia as a reaction to these massive protests of 2011, 2012. These legislative changes were implemented one by one, the internet censorship or media censorship and also civil society activists were controlled by these laws about protests, the internet and foreign agents. We should not forget that this is also the period of the Arab revolutions. And there people were using the Internet to organize themselves. So Russian authorities did not want to have something similar in our country. So to control young protesters, they started to control social media[2], social networks. And they started to control some very loud actors, civil society members especially with this law on foreign agents. Another colleague in France, Françoise Daucé, did a remarkable research on the impact of this law on the profession of journalism[3].

However, back in 2013 when it all started we were not so aware of the consequences of this law about foreign agents. I remember that we were assuming that yes, repressions will start, but we were not really conscious of what it is. When we were conducting interviews with Memorial and other NGOs that were registered as agents, they said yes, it became very complicated from the financial point of view because they had to endlessly produce financial reports and for small structures of civil organizations even this was a very heavy work. But I think in 2013 people still could not realize that this law will be used massively and that it will be extended to personal labeling as foreign agents.

Sofia: I would not disagree with you, Olga, but from a different perspective, there were people in Russia who could sense the seriousness of this foreign agents law. I used to work for Memorial back then and they were saying, Oh, this is a very bad sign. And I agree with you that nobody actually understood why.

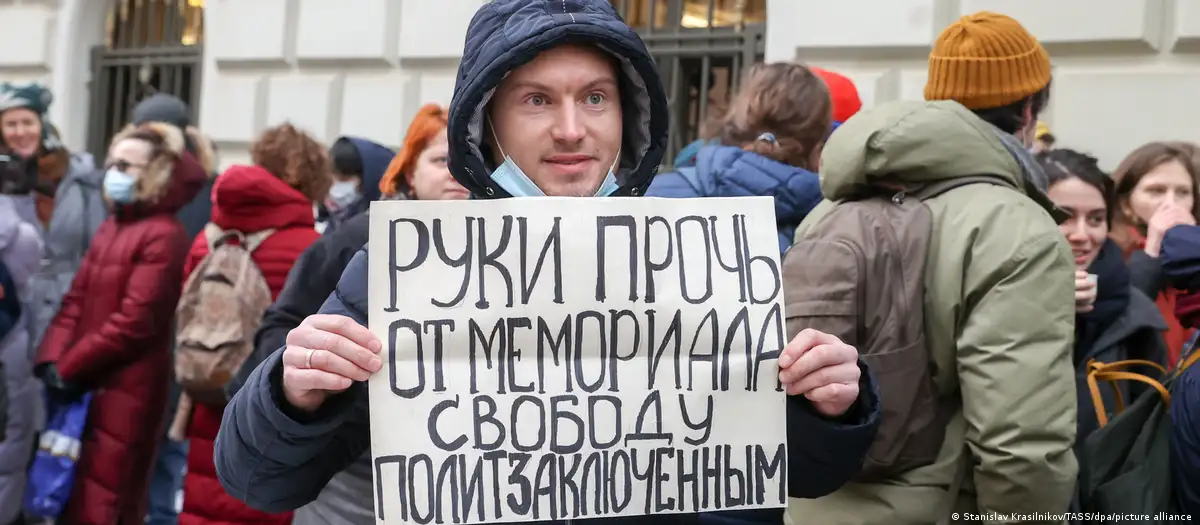

So yes, there were several policies and laws and agents law was one of them which set the grounds for separation and labeling people: Extremist terrorists, foreign agents, undesirable organizations... And right now it's ridiculous. Right now, every Friday there are new people labeled as a foreign agents. This process is also used for creating very specific narratives.

Olga: With all the narrative about, as you said, they created the progressed narrative about the so-called “fifth column”, in other words Russian citizens designated by the Russian authorities as persons working to destroy Russia from the inside on behalf of foreign states). I think it was the very beginning of this discourse of division of the society on brave patriots, loyal to the interests of the Russian state, and foreign agents, traitors to the fatherland. In short, it re-enacted the well-known narratives of the Soviet era..

Sofia: And this brings us to the question of the modern National State and the topic of threat. So if you're acting for someone outside, even if it's not an enemy, it's a threat to the sovereignty. And that's what we hear in Georgia right now. GD also says external funding is a threat for Georgians and for sovereignty. That's why we need to know why this NGOs are funded. The narrative is absolutely the same here.

Olga: But the question for Georgia, as well as for Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan is which version of the law they will keep. Because in Russia this law has progressed and changed and reshaped. And we are here at the ridiculous level of individual labeling.

But it took time, so, maybe in your country they will accelerate the process to introduce the worst version of the law sooner than it happened in Russia.

Tamar: A person labeled as an agent is restricted to fulfill certain duties in Russia, right?

Olga: Yes, it’s not only about finances even though a person must also produce a lot of financial reports. I once interviewed a Russian activist, exiled in Georgia , who was the first person to be labeled an individual foreign agent in Russia. She lived in constant fear, especially for her children, as the authorities threatened to take them away from her. She also explained to me that being a "foreign agent" in small towns or remote areas is even more complicated than in big cities. From one day to the next, you become a traitor to your country, and everyone knows it! You go out into the street and everyone looks at you.

[Stanislav Krasilnikov/TASS/dpa/picture allianc]

[Stanislav Krasilnikov/TASS/dpa/picture allianc]

Also an “agent” can not participate in the public sector. With this label you can’t teach at the schools and universities, you can’t be elected in public committees. And you can not have an advertisement if you have a youtube channel for example. So for us the first stage was attacking NGOs, then the media and then personal responsibility.

Sofia: This advertisement issue is important because journalists, like Ekaterina Shulman or katia Gordeeva, all had their YouTube channels and shows which relied on paid advertisements. And then they were not allowed to have it. And Katya Gordeeva shutdown the show, because she could not have the show without money.

Tamar: Maybe just because this law was progressed and revised gradually and also because not many people could consciously see threats it might bring upon there were no protests regarding this particular law?

Olga: I think in 2012 everybody was really tired already and also afraid. Because real repressions started after the 6th May 2012. That was the day when everybody understood that it was a serious thing – people were sent to jails for six years. And then they decided to introduce this law on agents. So the timing was not random at all. They knew that it was a good moment, because yes, protest continued somehow, still sort of throbbing, but then it slowly died out, because of oppressions.

But then the protests erupted again with Navalny's appearance. I remember very well that it was a really very important date in 2016, when the video on the corruption case of Medvedev got viral in social media. Even those Russian students that we had at our department of Slavic studies in Grenoble were telling me that it was the very beginning of their individual political history. It was a kind of a discovery moment for them that something is wrong in Russia.

2018 was the election year, so Navalny started preparational campaign targeting more and more young people in 2017. And the pro-Navalny demonstrations in 2016-2017 were not only massive, but also very young. As I remember those protests also were dealing with the question of foreign agents law, because when people were arrested during the demonstration, they were helped by NGOs labelled "foreign agents".

Tamar: Now, as both of you are outside of the country, did you observe any event, any political action as something hopeful? Maybe, Navalny's funeral was something special in that regard?

Sofia: I was thinking today exactly about the same question which I wanted to discuss with Olga. If we start from a personal level, the act from my side is my conscious decision that I'm determined to go back to Russia from time to time, to maintain this connection especially for my daughter, to raise her knowing that we have this link with our country, with our home in so many senses. I can’t imagine my kids not speaking Russian, not knowing our country house and not having this particular part of their identity. To keep this connection with Russia is inconvenient, it is expensive, also – nerve-wrecking, but for me, it's important that she has this connection and I also have an illusion that somehow I am connected with what is happening there.

But I think there are actually quite a lot of things that we would never probably call conscious political acts. We hear about the teachers being fired for not showing the Russian map with Ukraine on it. Yes, there are these new maps that have been issued that everyone should use in the classroom. And not using that map also is a political act.

As for the bigger scale, yes, I would refer to Navalny's funeral. for me, the amount of people who went there, openly saying that they've been with Navalny for seven years; that he's a victim of this regime, yes, it all is a very loud political act. There are also a lot of women who help Ukrainians who are taken to Russia. We know that many people from the occupied territories were taken to Russia. So there are Russians who show support, who help them. And yes, here we have volunteering again as a political act; again we have this ‘small deeds’ system that is built on human empathy; on human gestures of showing support.

But we need to keep this question open, because I regard it as super important to never stop finding examples of resistance in the society that has been oppressed.

Olga: I will say something really strange now. I wasn't shocked at all by the death of Navalny. I understood that a lot of other people were profoundly shocked by the fact of this death. My Russian friends in Georgia and France told me that it was the worst day of their life for the past two years. For me,the biggest shock was the beginning of the full scale war in Ukraine. For me that particular day was a kind of personal drama. And after that I changed. I became somebody who is very sensitive about war-related things. For instance when I went to Ergneti and Lia from the museum was describing things related to war it was shocking and emotional.

I know I have this very strange position now: I'm rather close to Russian immigrants, activists, and volunteers, but at the same time, I don't completely share their political sensibility and temporality. All my political activism, all my political actions are based today with Ukrainians. So I made a choice directly after the beginning of the full scale invasion. I went to the Ukrainian organization which sends humanitarian aid to Ukraine and at the beginning it was rather complicated for them and for me. We were trying to find my place there, but then we did. So I completely changed my focus. I completely decentered my world. I don't think that we can act similarly to how we acted in 2011-2012. What we can do now politically is to support political prisoners for instance in Russia. But I don't think the elections in Russia and other political events will change the situation. Nor am I sure that the organization of the Russian opposition in exile is of crucial importance. The important thing now is to help Ukraine. Of course, I know the information, because I teach all these at the university. But I don’t keep myself politically concerned with it.

Sofia: So yes, that question – what can be seen as a political act inside Russia right now – still hangs there. Olga and I are in a very similar position because the beginning of the full scale invasion was something like a turning point. Of course, I don't want to claim the trauma narrative, but it's something that changed us dramatically. As for Navalny’s death, I was shocked, I guess, because, subconsciously, I hoped that he would always be there. But since that I haven't engaged with Russian political activists. I don't engage with the Russian community that much, especially with those who left the country after the beginning of the war. I am not interested in Russian politics. I really don't care who the new foreign agents are, for example. And I don't follow the lectures. I don't go to Russian events.

And that's the question for me: Why? I keep asking myself that. And that's a good question. it's either we are doing it consciously or...

Olga: Or it is a coping mechanism.

Sofia: Not out of anger for sure. Maybe what I will say now will extend my haters list, but still, I need to say this: We left ten years ago and we had conscious civil reasons for that. And we had our established circles and friends and things that we do also consciously to stay active. But some of the Russians who left after the war, they reached out for help and support from the Russian diaspora; and yes, it is our choice and it's a moral choice for us to help Ukrainians instead.

Olga: I'm helping Russian activists of course. Some of the Russian activists who recently left Russia live in my home in France at the moment. And that's not a problem. But I don’t concern myself with Russian politics anymore. While for them it's still important. I see that difference between us. I prefer to be doing things for Ukrainians. Even at the university, for example. With my colleague, from Grenoble we tried to bring Ukrainian scholars to Grenoble and let them work there. I prefer to use the resources that we have, the capital that we have at the university to promote Ukrainian scholars. And yes, I think it's a responsibility of all the Western universities to offer more space for “others”, not only Ukrainians, but all those scholars who are marked as ‘others’, non-Western.

That’s why it was important for me to come to Georgia on my sabbatical year in 2022. I felt like I couldn't stay in France because there I felt far from the events important to me. And I discovered Georgia. I discovered the Georgian position and I believe that it is also very important to bring this via Georgian colleagues to France; so it's not just about Ukraine. It’s about decentralized perspectives.

Sofia: Oh, thinking of decentralization, actually, there is one dimension in Russia that interests me very much today – it is a decolonial movement that started in Russia. There are activists from Buryatia and from Yakutia mostly in telegram channels and instagram pages and I follow them with great interest. The government does not pay much attention to them at the moment, maybe they don’t think these small initiatives yet matter. And yes, we can’t say that these people have something close to being called a movement, these are just small initiatives in different forms, for sure in dialogue with each other, but not really united. So there they are and we will see.

On the other hand, I also acknowledge my privilege to be working in the Western university and to have access to the actual resources to decentralize studies from Russia to other regions which did not have a chance to have a prominent voice. And I try to help Russian and Ukrainian scholars to integrate in the European academic system; I try to increase visibility of the authors with almost no voice and to change either Russian-centric or Western-centric perspectives seems super important to me.

...

The conversation was recorded in Tbilisi, on 19th of April, 2024 for the INDIGO book about Protest and Resistance.

Less than a month after this interview, on the 14th of May, on the background of massive protests in Tbilisi, the Parliament passed the draft law during the third and final hearing.

Sofia Gavrilova’s latest article – Autoethnographic Reflections on One’s Own Imperialism

– is available at the February Journal website, in the issue 03 Decolonizing the Self: How Do We Perceive Others When We Practice Autotheory?

______________________________

[1] Bronnikova Olga, Gavrilova Sofia, Margvelashvili Tamar, "Finding the common grounds: visibility, cooperation and tensions between Russian and Georgia civil society initiatives in Tbilisi, 2023", Problems of Post-Communism, to be published in 2024

[2] “‘In Google we trust’? The Internet giant as a subject of contention and appropriation for the Russian state and civil society.” Olga Bronnikova, Anna Zaytseva, published in the publication: “Infrastructure-embedded control, circumvention and sovereignty in the Russian Internet” 2021-05-01. https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/issue/view/693

[3] https://muse.jhu.edu/article/579308/pdf

We Recommend