Unmuted Walls

31.05.2024 | 15 Min to readPolitical graffiti and its many facet

Mitja Velikonja, PHD, the Professor of Cultural Studies and Head of the Center for Cultural and Religious Studies at the Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. He views culture studies as an emancipatory science and tirelessly follows its bottom-up perspective on life, quoting William Blake to explain why his first step always is to be a flâneur: I tend to seek ‘world in a grain of sand and heaven in a wildflower.’ It is about seeing deeper ideological meanings and political consequences of everyday practices and everyday objects. The driving force is to see how all these big social currents are reflected on the walls. “I go to explore the city and then I deliberately get lost. This I see as a vital precondition to understand it,” - he adds.

Mitja Velikonja has been studying urban subcultures, post-socialist nostalgia, and the ideology of “Euro-Atlantic integration” – the new Eurocentrism or “Eurosis”, as he calls it ironically in his awarded book from 2005 - for more than 30 years. His photo-documentations of the walls from various cities from Beijing to Los Angeles, from St. Petersburg to Tirana - reflect times from the 1990s and onwards. The English version of his book Post-Socialist Political Graffiti in the Balkans and Central Europe, later translated in five more languages, was published by Routledge, in 2020.

...

T.B.: What are the most current political and social tensions reflected on the walls that you’ve observed in Ljubljana?

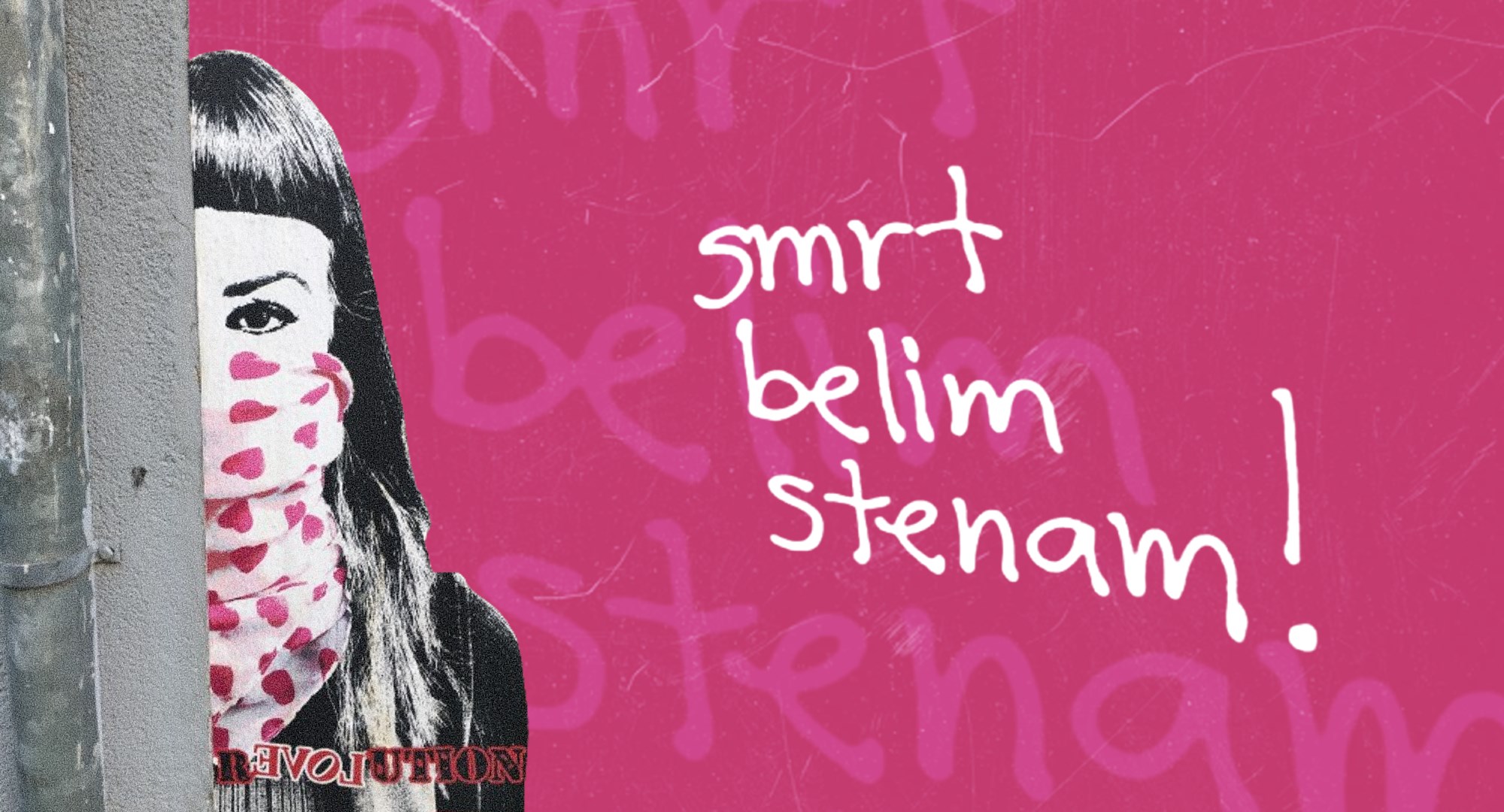

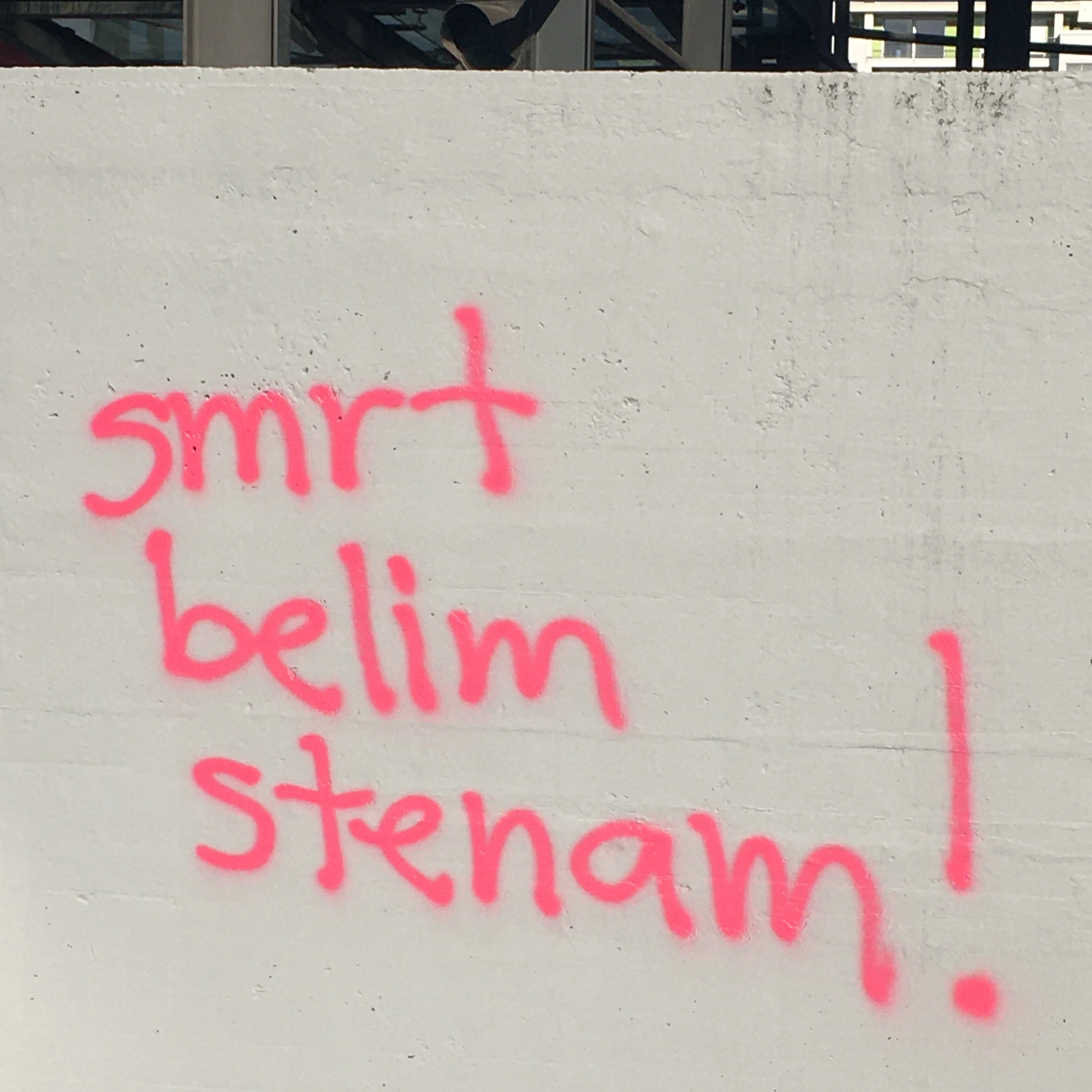

M.V.: The images on façades always grasp global and local tides of tension and social turmoil. No border is strong enough to keep them in a certain urban setting and geographical frame, they are the “litmus paper” of what’s going on at home and abroad. That’s why I view them through the lens of the glocalization concept (developed by Roland Robertson) of simultaneity and co-presence of global and local tendencies. Certain issues reflected on our walls might be characteristic only for Ljubljana, some not, they are part of wider developments. Anti-gentrification calls, for instance, are in this sense glocal – they strongly object turning neighborhoods or entire cities into tourist attractions, that is tourist traps; they criticize how this affects mortgage and rent prices, unattainable for young people and those who really needs decent housing. That kind of graffiti fiercely condemn this process of transforming liveable places into ghost town for elites and entertainment parks tourists. There’s lots of them in Ljubljana now. The second topic very much presented on our walls is gender related: lots of feminist, lgbtq+, in general anti-patriarchal graffiti and street-art pieces everywhere (especially during the two annual feminist festivals and gay pride). Illegal public messages in forms of graffiti, stencil, stickers, posters, different installations, paste-ups and in other street-art forms are made also by members of different progressive subpolitical movement, like AntiFa, alterglobalists, environmentalists, squatters etc. Since Slovenia is on so-called “Balkan migrant route”, there are quite some graffiti supporting refugees from the Middle and Near East and condemning European – and Slovenian – structural racism against them.

However, since political graffiti is basically a mean of political communication, all these are confronted by the opposite ones - right-wing, patriarchal, neocon, racist and homophobic graffiti – in so-called cross-out wars. Political graffiti turn urban spaces into, mildly said - political agora, or, in more direct terms, into political battlefield.

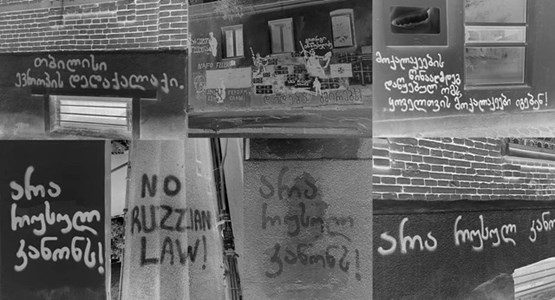

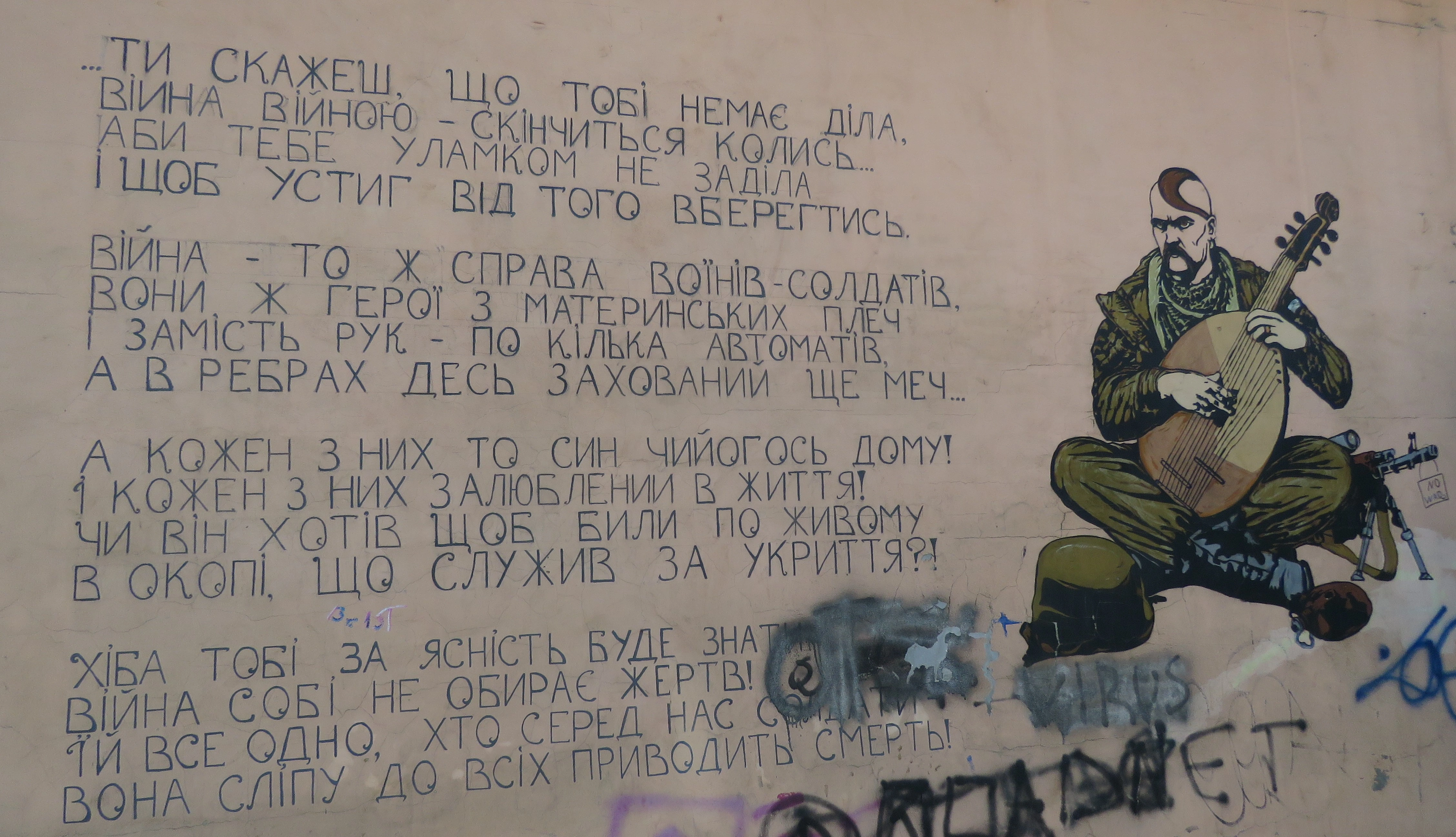

At the moment, the two burning global issues that are reflected on the façades practically everywhere are the ongoing bloody conflicts: war against – not in, but against - Ukraine and genocide against Palestinian civilians in Gaza Strip. I’m following graffiti related to the latter mostly on internet, although I have taken photos of some of them already. But when it comes to Putin’s aggression, I took hundreds of them everywhere I traveled in the last two years: in US, in different Central European and Balkan countries, in Georgia, I was in Ukraine twice. Most of them are of course anti Great-Russian, supporting Ukrainians which are under the siege. Just last week I photographed “Fuck Putin”, signed with an anarchist sign, in Skopje, capital of North Macedonia. However, I also found those who are against Ukraine, repeating Putin’s regime mantra of “denazification”. In most of the cases, confrontations between the two sides start literally overnight. Here’s a recent example from Ljubljana: an eerie call to Putin “Putin vrž že to bombo” (“Putin drop the bomb already”) was immediately and wittily transformed into “Rasputin vrž že bombone” (“Rasputin drop candies already”).

T.B. I’ve often thought about the authorship of graffiti, and I’ve tried to imagine who are they who leave these messages on the walls, in other words - their anonymity is quite attractive as well as their determination to inscribe names and nicknames on the walls.

M.V. I understand graffiti as illegal visual interventions in the public space that actively interact with its (aesthetic, political, cultural etc.) environments. Each of them is in a broader sense of political act for the simple reason that they should not be there, that they are not allowed. Graffiti writers take freedom that no one grants them, so they are essentially transgressive. But still there are those which pay more attention to aesthetic craftsmanship and perfection than to direct political message. In the first group, in so-called aesthetic (or subcultural) graffiti, their style, techniques, “artist’s touch” identify its author by themselves. Tags are actually (nick)names, so it’s for anyone in the scene crystally clear who sprayed them. These kinds of graffiti poeticize walls – while the political graffiti politicize them, they make them political. This latter group of graffiti radically differ from the aesthetical ones since their ambition is not aestheticization of urban surfaces or self-promotion, but activism. They are, as goes the title of Slovenian version of my book, “images of dissent”, they challenge the political and social situation in a certain society. While some of them are really a spontaneous “street reaction” by unidentified authors, most of them are made by organized (sup)political groups. So not by “usual” graffiti writers, but by activists with spray cans – there’s a clear division between them. In many cases they proudly add name of their group or movement, sometimes even FB account, or QR codes on their stickers. Political graffiti and other types of street-art are just another way of expressing who they are and – in short words, typical symbols, efficient slogans, recognizable colors, often offensive diction - their political agenda. So, a complementary type of political propaganda, the informal one, the one targeting specific public with their “street cred”. The same goes with the football-fan graffiti, murals, stickers etc.: just a brief look into any of the walls or street light pole or small metal gates for electrical cabinets anywhere in Europe explains which hooligan crew “rules the city”.

Main narrative strategies of political graffiti are simplicity, directness, and repetition. I once called them “political haikus” on the walls: metaphorically speaking, they don’t beat around the bush, but they hit the wall. Political graffiti do not explain the situation, they don’t interpret – their method is to strike, their ambition is to be completely understood, their method is shock. Messages in political graffiti are not polysemic (as in the aesthetic ones), but rather cumulative – they say one thing, and one thing only, in many ways. For example, Yugonostalgic graffiti combine the image of Tito and the defunct name of Yugoslavia, acronyms from “those times”, partisan slogans, red star, and proletarian symbols.

T.B. Has political graffiti in Ljubljana a long tradition? Please accept this question from the post-Soviet city where public space was not simply limited, but clean to the extent of becoming sterile; walls could not reflect all the undercurrents of social and political life; walls mostly kept silent.

M.V. Hm, I’m scared of empty walls in general. If I see lots of intact, painfully white façades, I have a feeling there is something wrong in the society it surrounds – that I’m in totalitarian Legoland, whether this totalitarianism is political, religious or the result of gentrification. Graffiti is a “silent voice” of the urban space, they bring discussion wherever they appear, they are signs of an openness, of plurality of opinions. That’s why I'm a fan of them – but precisely because I’m a fan, I’m very critical of them. I don’t romanticize them; I rather see them in their whole complexity. Yes, on one hand they are very liberating, emancipative, they give opportunities to voices and demands of marginal groups and individuals – to all those with communication deficit - in the society to be visible. But they can be also oppressive, they can reproduce negative stereotypes and advocate social injustices. So, they can be media of both, resistance and repression – the same as for example jokes. Orwell once said that every joke is a tiny revolution: it mocks the power, social hierarchies, existing system as such. I would I add that joke can be also a big counter-revolution, something regressive, unfair.

My hometown Ljubljana has a long tradition of public expression of political views – in Socialist times, students wrote slogans against Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, against American imperialist war in Vietnam, against the ruling “red bourgeoise”, so the Communist elites. But two periods were particularly rich with political graffiti: in WWII, when Slovenia was occupied and dismembered by Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and Horty’s Hungary, walls of Ljubljana and other places were flooded by graphically simple, but highly persuading antifascist graffiti. Made overnight by partisan activists, they were part of the organized resistance - a colleague of mine Helena Konda wrote an excellent book about them. Brushes, leaflets, and posters glued to the walls were as important weapons as guns carried by partisan forces. And in times civil society movements from the late 1970s to early 1980s, walls were again full of sharp punk, feminist, gay&lesbian, environmentalist, pacifist etc. messages, symbols, and images. I must also add a recent period (2020-2022), when most different forms of political graffiti and street art were part of protests against Slovenian authoritarian right-wing (Trump-like or Orban-like) government.

This inspiring environment contributed to my decision to write a proper study about political graffiti that would include – unlike some other who remained more descriptive – also well-structured theoretical background and efficient methodological tools to better understand and research this fascinating urban creativity. Another ambition of my book was to show how it is old as the humanity itself, so to argue that not everything started in New York or Philly in the 1960s and 1970s, as we could read in many Westcentric interpretations of graffiti and other illegal visual interventions in public spaces. Recently I visited an old Gothic church in Slovenia, full of small engraved inscriptions over the frescoes which were in fact a local chronicle in form of scratchitti from 600 years ago. In a tourist cave dozens of metres below the earth in Karst region, I took photo of a perfectly preserved “tag” from some guy from 1571, made by charcoal. Or let’s recall more famous example, all kinds of inscriptions in the ruins of Pompeii.

Returning to your question: empty walls are as interesting as graffiti-covered ones. It is as important to study graffiti as it is important to study the lack of them. These kind of research must pay attention not only to graffiti, but also to methods of their removals (bleaching over) or ways of confronting them (crossing out, changing original meaning, spraying over them, but preserving the lower layer to see what was written before etc.). Then, we have to pay attettion to locations where graffiti are immediately bleached over, literally overnight: on buildings of authoritarian institutions (churches, army, police) or of governmental institutions or of headquarters of political parties.

T.B. Question about time and space while analyzing graffiti is very important, as you discussed the glocalization approach, it was even clearer.

M.V. I approach graffiti in two steps: first as a flâneur, as a superficial observer, to collect the first impressions, to “feel” the place; and then as a proper, systematic researcher, “combing” the urban terrain. Spatial and temporal contextualization is crucial to understand these two backgrounds of a certain phenomenon. There’s no text outside the context, that’s the methodological basis. Boring political situation causes and is reflected in boring graffiti-scape. But the more dificult time and the more controversial space there are – the more political graffiti, the more direct are their messages, stronger. For example, it happened I was working in New York in times of Trump’s inauguration in the late January 2017. This city is already one of the most vibrant centres of graffiti and street-art culture – but at that particular time, and together with other types of protests like Women’s March, all boroughs were covered in anti-Trump, hm, everything: graffiti, murals, stickers, stencils, chalk-art, sidewalk-art, scratchitti, random inscriptions, paste-ups etc. etc. etc. Messages varied from condemning to ridiculing him, from being bloody serious to ironic, from warnings to promising resistance. I’ve never seen or heard of anything similar to the intensity of this “street reaction” against anyone.

Then, political graffiti appear more often also near autonomous cultural spaces, squats and universities, the usual “epicenters” of subversive activities. I was recently giving a lecture in Graz, a cozy and quiet Austrian city – with lots of graffiti and street art addressing the burning social and political issues (from environmental to antifascist, from feminist to antiimperialist). And lots of football-fan graffiti and stickers as well, to be honest, they are part of literally every European cityscape.

One of the most important questions in graffiti studies, “graffitology” as I call it, is how effective they really are, what’s their (political) reach. Graffiti are out there for anyone, but not many people really see them and even less consider them, taking them seriously. We are not taught to watch and understand them – schools, media, popular culture in general do not cultivate or advance such sensibilities. Only few opinion surveys were made so far, but they are showing rising perception of people to this specific urban creativity. The other indicator that they resonate is that authoritarian institutions and individuals react immediately to them, bleeching them over or confronting them with counter-graffiti. If graffiti would be really powerless and overlooked, they would not cause such fierce backfire.

T.B. As time passes the crisis resolves, the context fades and graffiti are still on the wall as stagnant, as a frozen artifact of the past. Or how do you view old graffiti? Do they still communicate to the audience, or all the agency drains out of them?

M.V. Graffiti are, as all other media, on one side historical documents, “time capsules”, they capture essences of certain periods. For example, on the wall of Ljubljana’s main street there’s “scar” (= still visible old graffiti) dedicated to Tito and, surprise surprise – Stalin! It must have been made sometime between 1945 and 1948 when Yugoslavia followed Soviet examples and Stalin was venerated here as well. But after that: despite destalinization that inscription remained until now, obviously Yugoslav authorities until 1991 and Slovenian from the independence on were/are graffiti-blind, they did not see what is so obvious. Another case: neighboring Croatian region of Istria is full of pro-Yugoslav and pro-partisan graffiti (and some also dedicated to Stalin and Red Army!) from the afterwar period (1945-1947) when there was a territorial dispute between Yugoslavia and Italy over it. A young scholar from that region, Eric Ušić, is now publishing a comprehensive book about them, worth to read.

On the other side, political graffiti from old times are reproduced, acquiring new meanings. For example, new versions of partisan, proletarian, anti-imperialist graffiti or some iconic images from the WWII and immediate afterwar period are appearing on the Slovenian walls (and elsewhere in post-Yugoslavian region), calling to resist new forms of fascism, ruthless capitalism, poverty, social injustices and new imperialisms.

T.B. You already answered this question, but we left it open: whenever the context is hot and debated then what kind of power graffiti has?

M.V. Even hotter, to give you the most general answer. Political graffiti appear in a palimpsest manner, one over the other over the other over the other etc. etc., and the diction is becoming sharper and sharper, a real crescendo. The real social and political impact of graffiti is impossible to measure – at the end, that’s the same as with all other form of creativity, right? Do songs, poems, novels, movies change the world? My answer is – not directly, expecting that would be an illusion. But they can help people understand this world differently, they can challenge its ideological self-representations and encourage people to change it. They can be a strong motivator, an inspiration.

T.B. How did the digital era treat political graffiti?

M.V. I remember well the great concern at the beginning of the digital era how this will affect the existing, so already old-fashioned media, and graffiti being one of them. Contrary to paranoic expectations they did not disappear but took advantage from it. Internet contributed significantly to the spread of graffiti and street-art aesthetics and politics globally: in a blink of an eye, we can check what’s going on in the graffitiscape of Nairobi, London, Buenos Aires or Athens, come in contacts with other writers (or with political activists with sprays), get inspirations from their social media or even download and use their templates.

T.B. Maybe even messages are shaped differently, let’s imagine the TikTok effect on the phraseology and wording of graffiti too.

M.V. That’s true, digital culture changes not only forms, but also contents and diction of messages – in all fields, not only in (urban) cultures. Who could, for example, expect to experience “twitter diplomacy” (or “twiplomacy”) as we did with previous American president? Things are changing also in graffiti and street-art culture: as mentioned, some graffiti and stickers today serve just to point at certain web page or FB/IG account.

We are in transitional period, with graffiti preserving also some more traditional roles: in Ukraine under siege – I was twice there in the last year – I took photos of textual graffiti with parts of poems by some classical and contemporary poets like Lesya Ukrainka, Mykhailo Drai-Khmara Serhiy Zhadan and others. Poetization of the streets is the same time also their politicization.