Tbilisi the Fantastic and Post-Fantastic | Zurab Karumidze

15.03.2024 | 12 Min to readThis demo version of Tbilisi biography, seen as the mixture of Eastern and Western flavors, was originally written by Georgian writer Zurab Karumidze for the festival held in Paris, in November, 2023 Un week-end à l’Est Tbilisi (LE FESTIVAL DES CULTURES DE L’EST / 7E EDITION).

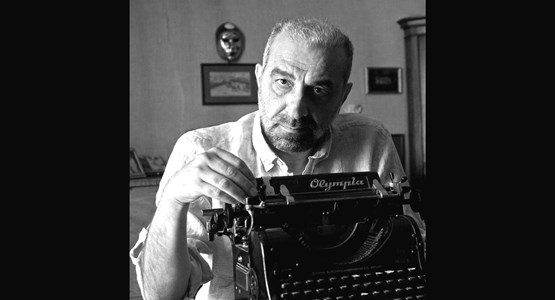

Zurab Karumidze is the author of Dagny or a Love Feast

If you open the volume of the History of Tbilisi, the very first sentence reads: “In geological terms, Tbilisi and its environs are the seabed which was formed in the Tertiary Period of the Cainozoic Era (there are layers of the Cretaceous Period underneath).” Indeed, fish and mollusks used to live here, and billions of bio-chemical processes churned and developed. Such geological origins predetermined the genetical code of this city, which throughout its history existed as the sea of a very special kind – the Winedark Sea. Wine was the substance which brought the dwellers of the city together, which stimulated and boosted its social bonds, social fabric, creative life. Tiflis would be compared to the two-faced god Janus, with one face turned eastward, and other turned westward. The middle eastern type of city of wine is an oxymoron because they don’t drink wine in middle eastern Muslim countries. However, this city has always had multiple identities, cultural and ethnic, which it combined harmoniously. Georgians, Armenians, Azeris, Jewish, Yezidis, Russians, Germans, Italians, French, Poles, etc. Jewish synagogue, Muslim mosque, Georgian Orthodox and Armenian churches stand side by side, and also there are some remnants of the Zoroastrian Atheshga down there.

“Just be a good man and no matter where you utter your prayers!” – that would be the top maxim of the old city.

Wine was the ubiquitous substance in this city, a very special juice, like its blood, or the hot sulfur water flowing in its old veins. It was founded thanks to those very hot springs, as the legend has it. No wonder that the wine-drinking ritual turned into a popular art-form in this city, and the wine-talk was a sort of a literary genre: an emotional, passionate, humorous, and self-ironic talk: “If you fill me with wine then I’ll fill you with joy! Drink and enjoy!”

Feasting would happen everywhere: in the gardens, courtyards, homes, taverns, marketplace, even -- on the rafts down the river, crossing the entire city and back, which was very popular. The group of local artisans and craftsmen, who would sing and recite poetry, almost like the German Meistersingers, were the major characters in this socializing events. They were called Qarachokheli and had a specific dress code – black dresses and conic hats, almost like the Sufis. They were people of profligacy and generosity, spending in the evening what they had earned during the day; among them frugality was considered sinful; they were macho types, strong drinkers and good fist fighters. The other indispensable characters of old Tiflis merrymaking were Kinto – the street peddlers. They were good and dexterous dancers, sometimes dancing with a bottle of wine on their head, with no support. They also were good at drinking, and unlike the Qarachokheli machos many of them were gay. They had their peculiar humor and mannerisms. When Modernism came to town with its vocabulary, they would come up with the special kind of street cries: “Buy grapes, the decadent grapes!” or – “Here is parsley, the futurist parsley!” Both Qarachokheli and Kinto would mingle with other social groups of the city: with Georgian aristocracy, which was permanently in dire straits, Armenian bourgeoise, which was pretty well off, and emerging proletariat, which was ethnically mixed. Of course, such a mingling was made possible through the alchemy of the wine and the Georgian feast.

Tbilisi, the eclectic city of perennial, “movable” feast, full of sounds of Persian duduk, Azeri zurna, Mideastern and Caucasian percussive rhythms, and multipart folk Georgian singing and religious chant; the Italian opera was also there -- the city opera company performed just with two years lapse the pieces premiered in La Scala.

Such a diversity on such a small territory could not go without translation, and to hijack Umberto Eco – Translation was the language of Tiflis – translation of the city’s gorgeous landscape into architecture, translation of architecture into people, translation of religious, ethnic groups and individuals into each other, translation of East into West and West into East. It seemed that the spirit of the city was totally open towards the Other and the Otherness, and this is the foundation of creativity.

What kind of literature was on the bookshelves of medieval Tbilisi households? Old Georgian writing was mostly religious, except for the secular poetry which developed in high Middle Ages; but those belonged to the monasteries. Relatively more mundane literature was preferable for the city people: love poetry written by Georgian aristocrats and kings, translations of Persian, Turkish and Arabic poems, and romances. And of course, every household kept its copy of The Night in the Panther Skin by Shota Rustaveli – Georgia’s national epic.

The Russian conquest in 1801 brought Georgia close to Europe, as the early 19th century Russia was more European than it is today. And yes, Europe did allure Tbilisi and Georgia as such; for 300 years, from early 18th century the narrative was there – Georgia belongs in Europe! The first symbolist manifesto (1916) of young Georgian poets read: “The second holiest land after Georgia is Paris!”

Through that indirect rapprochement with Europe, Georgian literature embraced bits of Classicism, as in the poetry of Alexandre Chavchavadze; the full-fledged Romanticism epitomized by Nikoloz Baratashvili, and Critical Realism – by Ilia Chavchavadze, Alexandre Qazbegi, Lavrenti Ardaziani, et al. And yet, the most vibrant merger of Georgian arts and culture with the European comes upon the explosion and unfolding of Modernism in Georgia in 1910s-1920s.

Georgian Modernism, aka Tbilisi Avant-Guard was a belated one, because the country was on the periphery of greater European artistic developments. Though belated, the Georgian modernism acquired shape and features earlier -- at the turn of the 20th century -- in the works of two creative individuals: the primitive artist Niko Pirsomani, and the highlander poet Vazha Pshavela.

The unfolding of Georgian modernism fell upon three crucial episodes of Georgia’s history in the first decades of the 20th century: the collapse of the Russian Empire (1917), the establishing of the first Democratic Republic (1918-21), and the retaking of Georgia by the Bolshevik Russia (1921).

There would be no Georgian Modernism, without the genius of the place (genius loci), the spirit of the place where it emerged – the capital Tbilisi, which from Winedark-sea turned into the Fantastic City as it was called that time. The city opened up and give shelter to a new kind of people, who sang different songs and danced to different music – those coming from western Georgia, Kutaisi, and those coming from Russia. The Russian artists and poets were fleeing the Civil War which broke out after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution; they were seeking peace, mild weather and good food and wine for sure. When they arrived from the devastated Russian cities and saw electric lights in the streets of Tiflis, some would fall on the knees, kiss the land and pray to the lampposts. The elite of Russian Silver Age came (Nikolay Gumilyev, Vladimir Mayakovski, who was born in Georgia,) Osip Mandelstam, Sergei Sudeykin, etc). Tiflis had always been a multi-ethnic place, but it had never seen such an influx and diversity of creative individuals, who spoke all languages, including some poetic shibboleth, like the Transmentalism, and even Esperanto.

If you look at the urban centers of the global of Modernism – Paris, Berlin, London, New York, St. Petersburg, et alia, you need to look for the artistic cafés – you’ll see cafes as its dwelling place, Modernism was a café culture. Likewise, the notorious Tbilisi artistic cafes of those golden days were not just the place for booze and eating, those were the sites of education and knowledge. Poets and the artists would hold lectures, discussions, presentation of new books and other publications, theatrical and musical performances, and of course -- drink and smoke, darn much… clashing, debating, flaunting their manifestoes, holding happenings.

The Georgian Modernists were of two kinds: the Symbolists and the Futurists. The core of the symbolist movement was the poetic order of the Blue Horns (Tsisperqantselebi): Paolo Yashvili, Titsian Tabidze, Valerian Gaprindashvili, Kolau Nadiradze, et al. and their guru – novelist, dramatis, poet and essayist Grigol Robakidze (btw the first Georgian who wrote on Jazz music in 1920s). The Futurists included Tbilisi born, half-polish, half-Georgian brothers Ilia and Kiril Zdanevich, and their Russian co-travelers Kruchenykh, Terentyev, etc. and the predominantly Georgian Dadaist group of H2SO4 – Beno Gordeziani, Nyogol Chachava, Zhango Ghoghoberidze, Simon Chikovani,and Nikoloz Shengelaia – the future film-maker. There was one poetic animal among Georgian Modernists, who stood aside and above both groups and never would affiliate himself with any artistic congregation of his time and was regarded the King of Georgian poets – Galaktion Tabidze. And king he was, indeed, whose realm went beyond symbolism and futurism. But his is a separate story.

The towering figure of the Georgia fiction of that period – Mikhail Javakhshvili (executed in 1937), published his major European style modernist picaresque novel Kvachi; the other one -- Konstantine Gamsakhurdia -- writes his mytho-poetic novel Dionysus’ Smile.

The literary modernists were supported, if not overwhelmed, by remarkable visual artists: David Kakabadze, Lado Gudiashvili, Elene Akhvlediani, Shalva Kikodze, Petre Otskheli, Irakli Gamrekeli, Valerian Sidamon-Eristavi, Dimitri Shevardnadze and others. The modernist fad touched the Georgian theatre as well, in the revolutionary and innovative stage productions by Sandro Akhmeteli and Kote Marjanishvili. The same is true of Georgian cinema, which dates back to early 1900. The first full-scale documentary movie was filmed in 1912, by Vasil Amashukeli. After him came Alexandre Tsutsunava, Ivane Perestiani and the avant-guard directors – Nikoloz Shengelaia, Kote Mikaberidze and Mikhail Kalatozishvili.

The Modernists – both domestic and expats -- proved a great addition to the city’s merrymaking. The traditional Tbilisi feast was enriched by performances of odd and weird young people, reciting their poems sitting on the trees, or from carriages passing by on the main avenue, or impromptu podiums at the marketplaces, or academic stages. The true and full-scale “theatralisation” of life began. Yet another Futurist group founded by Zdanevich Brothers and Aleksey Kruchonykh that time was called “41 degrees.” This name referred to three things: the latitude on which Tbilisi is located, the stronger than average alcohol drink, and the high fever, when you get delirium. Thus, with the advent of Modernist avant-guard the fever of the city went extremely high, with the delirious artistic language it spoke. [1]

Alas, this “theatralisation” of life and ultimate creativity lasted only until the end of 1920s. After that came gray zone of Stalin’s Socialist Realism in arts and Totalitarianism in everyday life. The modernists went through the Great Purge – some were executed, some fled the country, some transformed themselves into the staunch supporters of the new ideology and esthetics.

But after the death of Stalin (with the advent of jazz music and some pieces of American writing and cinema during the Khrushchev Thaw) the creative charge of the city exploded again; later, in 1960s and 1970s new generation of writers and artists emerged. Georgian cinema produced remarkable works, which got international acclaim: the Shengelaia Brothers, Otar Ioseliani, Giorgi Danelia, Rezo Gabriadze (as a script writer), Mikhail Kobakhideze, Rezo Esadze, Irakli Kvirikadze, Alexandre Rekhviashvili, and many more, brought back the art to town, the art full of irony, sadness, lyricism and improvisation. The same is true about the theatre – Mikheil Tumanishvili, Robert Sturua, Temur Chkheidze, et al., they deconstructed the false pathos and academism of Soviet theater and opened the space for post-modernist esthetic in the Georgian arts and literature. In poetry Shota Chantladze was remarkable, with his contemplative flaneur discourse; then came Anna Kalandadze, Lia Sturua with her ver-libre innovations; the prose was dominated by Otar Chiladze, Guram Dochanashvili, Chabua Amirejibi, Naira Gelashvili, et al. I would call this period and the people the Late-Fantastic.

The Post-Fantastic Tbilisi began with the collapse of Soviet Union and the Civil War (aka Christmas War) of 1991-92. Life started to imitate arts, revaluation of values, destruction, ethnic conflicts, domestic skirmishes, but also – steps towards open society and democracy, fledgling non-governmental organization, independent media -- we were discovering Postmodernism. New urban style writers emerged, the likes of Carlo Kacharava (a remarkable artist and writer), Aka Morchiladze, Davit Barbakadze, the Reactive Club, David Turashvili, and many more later: they were parodying the literary classics, cliches, stereotypes, styles, religious ideology, rereading, rethinking, and deconstructing the past. Notwithstanding the wars and socio-economic grievances, sufferings, deaths, refugees, disasters, political upheavals, which always brought “something new,” we still managed to make fun of our problems, turning them into new literary discourse, forging new urban language, inventing new narrative possibilities, moreover – inventing our new identities. transforming them through creative and carnivalesque shapeshifting. The 1990s were exciting times in Tbilisi.

As we go deeper into 21st century, it seems the creative life of Tbilisi is being concentrated on the floors and darkened rooms of the night-clubs (like “Bassiani”), which have already become well known in Europe. Moreover, the clubbing and political life of young people in the city merge: at the rallies in front of the Parliament condemning Russia and staunchly promoting Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic integration, supporting Ukraine, and confronting Georgian government, which sticks to a rather overcautious politics regarding Kremlin, the slogans carry the traits of a night club – “We Dance Together, We Fight Together!”

Tbilisi Culture is getting political and hedonistic, at the same time embracing major global challenges of today – ruthless and assertive Russia from the North, the war between democracy and autocracy, climate change, pandemics, etc.

As for the arts, there are some very interesting developments in new Georgian cinema and theatre – take the Royal District Theater; and as for the creative writing, please, welcome Nino Haratischwili!

______________________________

[1] History repeats itself. Like over a century ago, the wave of Russians intellectual invaded Georgia last year, escaping draft and war in Ukraine, financial and business-economic limitations in their pariah state. Though most of those Russians are creative people, there has been no interaction between them and their Georgian colleagues; just mere consumption: Georgians consume Russian money, Russians consume Georgian wine, food, and weather -- no art, no creativity, as if Georgians and Russians here live in parallel worlds, which will never intersect.

We Recommend

What is happening to Tbilisi?

27.10.2023