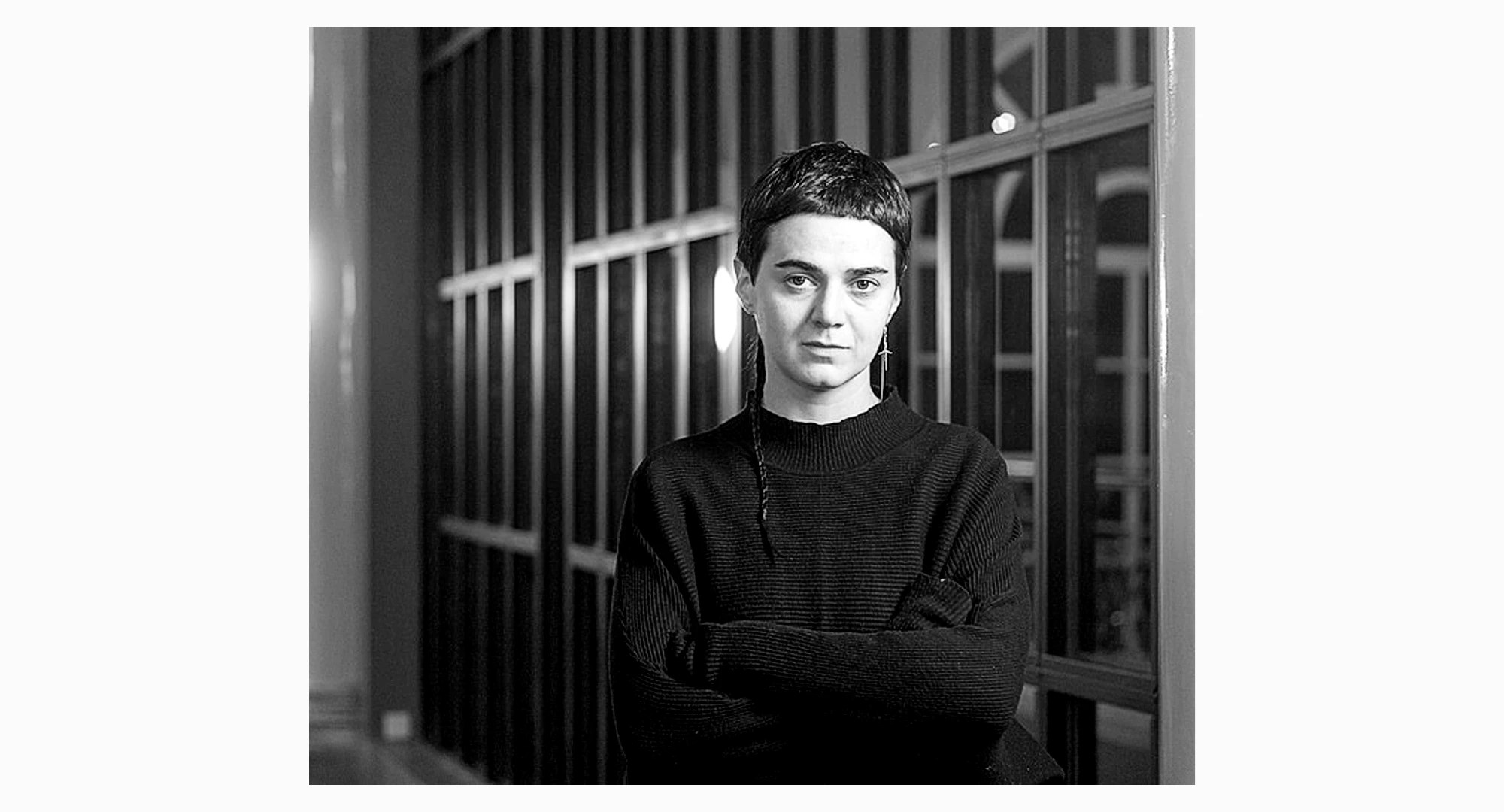

A Forgotten norm | Interview with Elene Naveriani

Indigo: Elene, the film is titled as I Am Truly a Drop of Sun on Earth. Is the environment depicted in the film similarly poetic or did you want to achieve contrast?

Elene: Actually, these words “I’m truly a drop of sun on earth” are recited by a black man when describing himself. This man is brought to France, a very foreign environment for him. His name is Frantz Fanon, his book is called Black Skin, White Masks and it explores the racism and dehumanization of human beings that is so characteristic of colonialism. In short, Fanon says the following in this book.

“I am black: I am the incarnation of a complete fusion with the world, an intuitive understanding of the earth, an abandonment of my ego in the heart of the cosmos, and no white man, no matter how intelligent he may be, can ever understand Louis Armstrong and the music of the Congo. If I am black, it is not the result of a curse, but it is because, having offered my skin, I have been able to absorb all the cosmic effluvia. I am truly a ray of sunlight under the earth.”

That was the phrase that started it all, because I saw how one person understands his connection with the universe, how he becomes whole through it. The current state of the film is no longer directly connected with the title, it could have many other titles now, but that phrase is still the connection with the point from which I started the whole film and that’s why I decided to leave it.

Indigo: You explore several characters in the film – you have a Nigerian emigrant, who works as a porter in the market and a woman who stands in the street… Were you were initially interested in one particular minority and then moved on to others?

Elene: This topic – the different and marginalized – is very general, I have made three films and all three of them are connected with my personal experiences. How I start working, where my interests come from – all of this is very personal. I started to think about this last film with African emigrants, because of my girlfriend, who’s black. More specifically, because of what I noticed four years ago when we went to Georgia together. I hadn’t walked the streets with a black person before that. I didn’t know how Tbilisi residents usually reacted if your friend was black.

Indigo: How did they react?

Elene: With an absolutely irrational hatred. Take for example, the fact that they believe that black people smell differently. This is just a misconception, an absolutely irrational belief, which they revive and use whenever they meet a black person for the first time. They demonstrated acquired aggression with that.

Indigo: Did you defend her?

Elene: Defending needs to be learned too. I thought then that if I responded directly to that aggression, my friend would guess what was happening. However, one day she told me herself to not worry about it, she said she was used to such things. That’s when I realized that such things could not only happen in Georgia, but also in the country where she resided.

Indigo: But it’s still interesting how racism can be manifested differently in Georgia and Western culture.

Elene: Each society has its own, individual attitude towards racism, what we see in the United States often doesn’t reflect fully European or Georgian racism. In Europe they say that racism, as well as other minority struggles, has been overcome. They say they’re now free of racism, that non-white people are protected by law just as white people are. But the problem that hasn’t been solved there or anywhere else is white patriarchal supremacy. This is a system that creates images, ads and all the mass products based on white standards. White is beautiful, straight and blonde hair is attractive, blue eyes are the standard of beauty and so on. When black children don’t see their place in society, when they see that what they have is not accepted, they try their best to become the kind of people that the dominant culture recognizes: they discolor their skin, straighten their hair… they had been taught that the blonder the hair the better. Mind you, decolonization hasn’t occurred yet and that’s the most important factor. Despite declarations and conventions, most people still don’t recognize what you are. Then you start to hate yourself, because you’re gay – in other words, you’re not normal. As if one type can hold the history of the whole race or community.

That’s unconscious racism. A clandestine racism that can be detected only in gestures. For example, you go for a walk with your child and you see a black person and you tighten your grip on your child’s hand, you don’t tell them anything directly, but you convey your impulse – be careful, this is a danger. You may not even think about it, but it’s embedded in you. In short, one body may remind you of many things and sometimes the first thing it reminds you of is danger.

So whether it’s in Europe or in Georgia, the problem remains the same and it’s called white patriarchy. I think raising awareness about that system will free many minorities from what we are all suffering from now.

Indigo: When you were making your films (I mean all three of them), was your goal to ask questions?

Elene: First of all, I was wondering whether I was also poisoned by all of this, because sometimes I noticed that I also carried unconscious information that I had never questioned before and suddenly I would realize that I had a certain attitude towards a topic, which had been someone else’s attitude at another point of time. So I started to think about the personal experiences that troubled me from scratch and then it was followed by the process of asking questions and arriving at obstacles. My first film was like that. I wanted to film personal struggles. I was involved in those struggles for a long time and I couldn’t figure out how to express them. I used my religious feelings as one of the main elements, because they conditioned me in reaching the next stage.

Indigo: When did you become more liberated internally, when you began making that film or when you screened it in Tbilisi?

Elene: I generally became free when I realized that the form I had chosen was the right one. Otherwise, I wouldn’t have been able to express all of this, because a verbal act wouldn’t have helped me. I had to speak about my sexuality and it was difficult to talk about all of this. I had many different tools at my disposal in cinema – images, sound and other elements. I managed to use all of those tools to say what I wanted to say. Actually, you’re right, here I regarded that film as a product that I had to create. I viewed it as a film that would not only enable me to express what I wanted to express, but also touch upon general topics. But it was different in Tbilisi. I actually told everyone: this is my life. The reactions followed from there. People would tell me “what a good film”, but in fact what they implied was: “oh, I didn’t know”. So I really was liberated there, because people who were very important to me evaluated it as my work and I managed to share with them what I wanted to say through my work.

Indigo: When you make films about minorities, when you internally confront the supremacy of power, how do you feel as a director? Don’t you think that role also implies the temptation of power? The temptation to use others in order to express yourself?

Elene: In some cases I believe I’m in the minority. When I worked on those films I had to interact with people who are the minorities within minorities. I knew I had the privilege of being an author. I knew I was the one who gathered all those people to work on the project and to fulfill my wishes. But I didn’t want to turn the people into tools and during the process I realized even more that the plan and script that I was following were unimportant; the things that those people were providing me were valuable. That’s why now when I watch the edited material, I realize there’s an important thing in the film that slipped away from me, that got out of control and I think it’s good. It seems like my characters have taken me even deeper to a place where I wouldn’t have ever gotten to on my own if I had spent more time with them. Therefore, I guess the best thing that I did as a director was to follow the characters – they were not hired actors after all, they played themselves and it meant they were playing something in which they already lived day after day – and it was all happening in parallel – despite being filmed, their reality was not discontinued.

Indigo: When you came to Tbilisi to do research and got to know them, visited them at work, had dinner at their apartment and helped them with something… once you became friends and they took you to a club, did you have a boundary set for yourself that you wouldn’t dare cross? Did you ever feel in danger physically or come to the conclusion that you didn’t “need” to know more?

Elene: I wanted a very delicate thing. I wanted to understand how two topics actually worked: emigration, with African emigrants and women, who stand in the street. I researched a lot of materials before getting in touch with them. I didn’t want to be unprepared. I needed to legitimize my own motives, but the environment I found myself in was still like a slap to the face. That was a good lesson. I realized my own privilege: yes, living in this reality is very difficult and yes, I fully entered their lives, but I had the opportunity to extricate myself from that life at any time I wanted. But they can’t do that, that’s their life. So I followed it till the end and during the research, I realized I was no longer interested in what I had written before that. I realized it was a collaboration with them, we’re making a space (in other words a film) where they can say what they want to say, where they don’t exist only for their own circle, they become visible for everyone; they speak and somebody listens to them. That’s why I didn’t want to hire actors, I wanted to see the real people and I wanted those real people to take part in the writing of their own story.

Indigo: Was it like walking on the razor’s edge? Because there’s a danger of giving that environment a romantic and exotic color.

Elene: Yes, I gave up all those parts in which I saw the signs of that. I didn’t even take steps to hold the story together or control the quality of their performance. The film doesn’t intend to make the viewers say they performed well or they were good actors. These people describe the environment they have to go back to after the filming is done in their own words. They play their own roles.

Indigo: Was there any indication that they were tempted to show their lives in an even worse light than it really was?

Elene: Probably yes. But it was pleasant for them to be on stage and perform. I believe they were tempted to perform what they know about themselves from outside. In other words, they were probably tempted to perform the image that the public has imparted on them. Of course that was a double performance – first of all, they were playing themselves, but at the same time, they were performing roles (sometimes romantic, sometimes exotic) that we imparted on them ourselves. However, they wouldn’t have been able to perform that outside image – how can you fully exit your body, your reality? Thus, they performed what they wanted to express about themselves; they offered me what was important to them. They placed an emphasis on themselves. They offered a different kind of cinema to me, they seemed to show me people that are living in emptiness and loneliness and sometimes they need someone to spend the night with. That’s why, while working with my characters the original theme of the film became even more pronounced: This is a film about lonely people, who try to get in touch with each other somehow, so that they can create some sort of relationship, but they can’t get connected and then the questions follow. Why are they together? What are they doing together? Why do they have these two-faced relationships? What is it all about? Is it about survival? Is it only about waking up alive the next day? I’m not talking about morals in this case, society is hypocritical as far as relationships are concerned and most importantly, there’s no contrast. I don’t show contrast in the film, because I can’t see it. What we see in the film is minority, and this minority creates a norm – they are the norm. This colorless, trivial, lonely and cruel life has no alternatives. I didn’t even try to describe that life in juxtaposition with other strata of society. On the contrary, I created one plane, I locked these characters in one universe (just like they actually are) and I believe the details that are invisible from layer to layer have become clear on that plane; now you watch them and realize that whatever you’re standing on is very down below you; there’s a foundation and it’s real, these people are real too. They’re frank and direct too, they don’t need to pretend, they’re not afraid of anything, because they have nothing to lose. They only have their lives, which become absolutely unimportant to them sometimes.

Indigo: When you talk about absence of alternatives, do you mean hope too?

Elene: They have no hope. If they had hope, they would be sad to watch. Hope is a very sad thing, we invented it for survival. They don’t need hope, they exist for the moment. For them, the only thing that is more important than this moment is tomorrow. Tomorrow they are going to face other dangers. In this case, I mostly mean women who work in the streets.

Indigo: Can’t you see all of this in other social strata and upper layers of society?

Elene: There are such different interests, expectations and priorities in those other strata that it’s impossible to talk about it. I believe we have lost what my characters possess. Every gesture is a sign of resistance with them. This is an existence in the form of resistance. The idea of my previous film was the same: the process and act of researching past and future battles and the desire to understand them. This is a moment when you put yourself in the shoes of the minorities in order to somehow understand something that is yours, as a foundation of humanity; how it feels to fight for another day. I don’t want to observe it all from outside as an anthropologist. I want to experience it myself, I want to become its part, it’s much easier for me that way, but as I already said, in the process of entering that universe, I still see my privilege of being able to come back anytime I want.

Indigo: I always thought you were realized in your job and that you always managed to find your own forms in contemporary art, how did you become interested in cinema?

Elene: I didn’t know how else to express all of this.

Cinema is one form of activism for me; if I don’t do it, then I will go out and become an activist in the full sense of the word. I’ve heard people say cinema is dying, that it’s in crisis, but this is simply not true. For me, it’s not dying, it will die only when there won’t be anything to say, because actually, it’s a very young medium and it helps us convey so many different things through visuals, forms and technical means.

Activism is a new form of cinema, which I think connects art and reality with each other.

Indigo: And you do all of this through cinema tools? Do you take only the form of art from cinema without changing the story?

Elene: In the case of documentary filmmaking, I can’t participate in the process the way I can with feature films. I need to be personally involved, to feel the story… I need to try the boundaries that I see in reality. These various realities, challenges and cares don’t have only imaginary boundaries, they also have physical and tangible boundaries. A large portion of this third film is shot underground, where their life takes place, where everything we talked about is happening. After ascending 20-30 steps, you see our everyday life – the downtown area and a multi-storied, fashionable hotel, but do you know how close these worlds are to one another? I discovered an inexplicable thing for me there: they live absolutely protected underground in their own environment, then they come up and become completely invisible. And if somebody notices them, it’s only to show contempt.

Indigo: But they don’t come into contact with us, isn’t the severance of the contact a mutual thing?

Elene: People, who have more privileges, have more means to preserve this connection. We severed relations; we don’t want to see it, to see how troubling it really is.

Indigo: The most important thing that our brains may not even be able to fully process is the absence of hope and living one’s whole life without any prospects.

Elene: Yes, probably it will be the most painful thing for them, but they can’t really think about all of this, because when you start thinking you see alternatives and hope. Of course, there are minority activists, for example, transsexual females, who self-reflect and even undertake academic research about their experiences, they perceive their lives within a political context, they go somewhere, want to discover something, but these are exceptions. Mostly, they don’t ask questions like: Why am I like this? What do I need to change? Survival is so important that analyzing one’s environment, putting oneself in a certain context is impossible. I have thought a lot about what we can do for transsexual females and males for example. Should we create educational programs? Should we teach them how to do certain jobs? Who needs it? Can you imagine them studying at a university? Therefore, first of all, we need to create a space, where they will be able to express their opinions with their own words. I had asked Bianca to start writing a diary and she actually did it. It’s important for us to be able to read it afterwards – let’s not pay attention to how they express their views, their syntax and so on. The main thing is for them to express them themselves.

Indigo: When during the editing process you heard about the deaths of two main characters of your film, did you think about changing something in the film (apart from feeling great personal loss of course)?

Elene:

On the contrary, what happened to Dan (he died from pneumonia, as soon as he arrived at the hospital he realized that he was disliked there and eventually he died due to the doctor’s indifference and lack of attention). What happened to Bianca (law-enforcers simply concluded that her death was a result of an accident caused by natural gas leak) was proof that I hadn’t invented anything, despite the fact that I did a feature film. I realized that no matter what I invent, it will never be worse than what these people experience in their lives. The deaths of both of these people were a very painful answer to my directorial questions.

I Am Truly a Drop of Sun on Earth won the jury prize as the best feature film at Queer Lisboa, Porto. The film also won the prize for the Best Director of Photography at Valladolid International Film Festival.

We Recommend

Elene Naverian - "Wet Sand"

28.12.2021