I Slept and Dreamed I Was a Butterfly

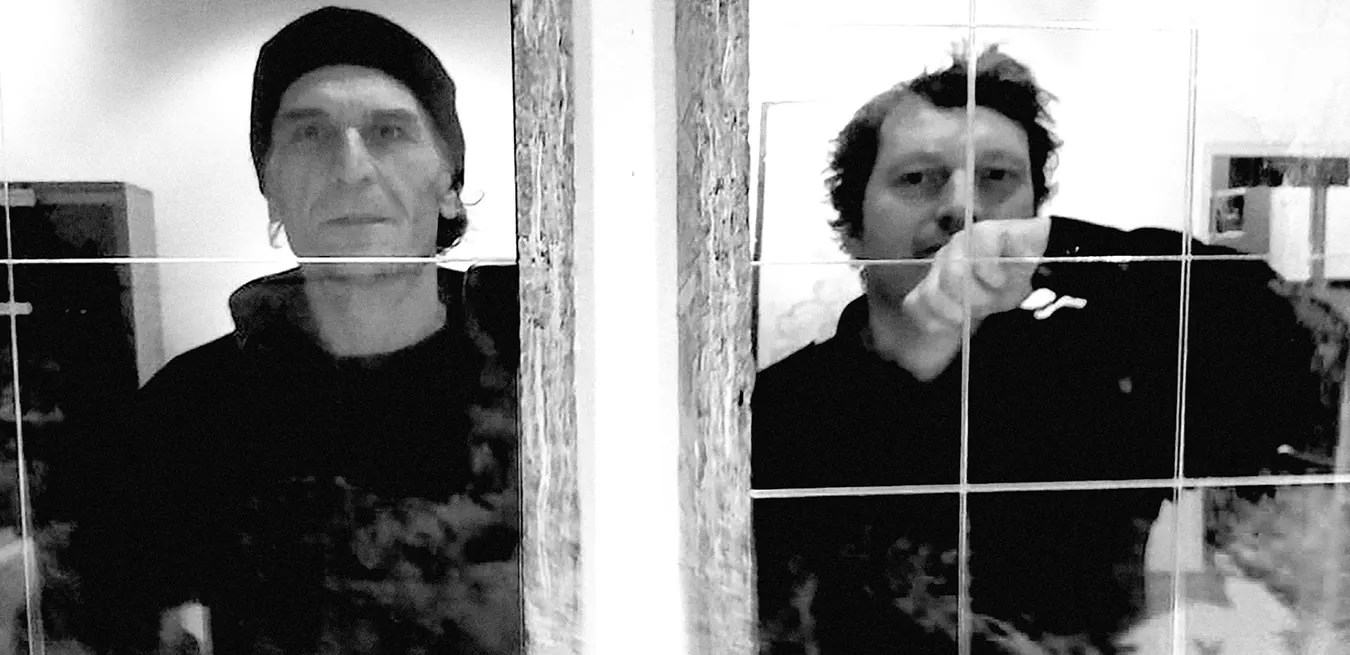

Lado Pochkua, author/artist

Mamuka Berika, musician/traveler

Lado Pochkua: If there’s anything I know, it is war. In all my incarnations—and I am a father and a husband, I became an author, and painting is what I’ve always been doing—I know how to survive a war better than anything. When push came to shove, I nailed it. Should a war break out here, half my neighborhood will be scared to death, but I’ll survive. Half of Brooklyn will literally die of fright, and the other half will worry themselves to death fearing relocation or standing in line.

But I will survive.

Mamuka: That’s because you’ve been through the war. But, generally, I disagree with you, Lado, when you say that war and peace are two different things. Both have been around since the beginning. They’re always present in our outlooks on the universe. Naturally, they can exist physically. But for some, peaceful times may equal military action.

Lado: When the August 2008 war broke out, I was in Budapest, living in a cozy, quiet house right on the riverbank. I used to jog every evening. I would cross a beautiful bridge to the island and run around it three times, nine kilometers in all. I remember making one circle on a comfortable rubber surface, one of the many you find all over Europe, that day. Then I grabbed my phone to check the mileage. And suddenly I ran into the news of a war in Georgia. I fell down and broke out in tears. I could see myself then—and I still do—kneeling on that rubber surface, surrounded by those ideal and idyllic landscapes on the Danube riverbank, and crying my heart out. My own helplessness broke my heart, when you read the news of a war in your country, but can’t get involved, can’t help in any way, can’t help your neighbor or some child escape—you can’t do a thing about it, so you fall down on your knees, on that comfortable rubber surface, and weep.

Mamuka: I was speaking with my son during those days. He was in Tbilisi at that time, and I was in San Francisco. “What are going to do?” I asked him. He replied, “Me and grandma will probably go to Turkey.” I thought… well, I imagined myself collecting tents for them, traveling to Turkey and looking for them.

Lado: War is cannibalism, just a different form of it. That’s what happened in Abkhazia. When a referendum, as a democratic leverage, fails, it is replaced by a war. Then this war is followed by all kinds of dramatic layers, and I keep drawing on these dramas to this day. That’s why I’m writing about this war. You know there were so-called wartime writers. I’m talking about the Soviet era. They wrote exclusively about frontline events, but I don’t want to be one of them. After I exhaust this autobiographical cycle of mine, I have different plans, like settling down in Tbilisi’s Vera neighborhood and writing ten stories about Tbilisi. Or I can go to Tsalenjikha or somewhere near Zugdidi and take abode in a Megrelian porched house, something to be like my version of the return to Ithaca. I may learn the Megrelian language and write about this learning process, about my country’s history, and how I got to know the locals in an everyday setting.

Mamuka: I realized the same thing when I arrived here in Adjara. Here’s what I mean. You know that my music is more like Japanese. I always try to compose and play something along the lines of Japanese tunes, Japanese philosophy. But here in Adjara I got a different kind of inspiration, a second breath of sorts. I recorded one composition, more neutral in character. And then I met a filmmaker I want to make a video for this piece. And he told me that the tune sounded Japanese. I told him, “No, my dear friend, you’re wrong. No way it’s Japanese! We’re now on Lake Paliastomi, and this is Zen. And Zen is present everywhere, on Paliastomi or Mars for that matter. Zen is everywhere where he who carries Zen is.” Now looking at that composition, I realize that it has hues of Georgian here and there, not Japanese.

Lado: Mamuka, what has reached out to you was called genius loci, the protective spirit of this place. This spirit is talking to you. Don’t forget where you are now, this place: The Empire of Trebizond, Byzantium, the Laz people, Mongols—after all, Adjara shows traces of them all, and then some.

Look, we just switched from war to peace in a blink of an eye. Have you noticed? Because talking about peace comes naturally to human beings. There’s no way I would want to talk about how Brooklyn, my neighborhood here, might be bombed. What I want is to look ahead and picture peaceful, productive times.

Mamuka: The aesthetics of military art amaze me since childhood—and you know, Lado, that I’ve loved, and still love, painting since childhood. And I don’t mean just military parades in oil paintings. I’m talking about battle paintings in general. Battles are always suffused with a peculiar kind of beauty, a certain kind of euphoria. When armies, determined and ready to go for it, face each other, it is beautiful. Sometimes I think that everyone going to war imagines himself right before dying. And I see its own aesthetics in it. Battles last for a certain amount of time, usually for half an hour or maybe three hours, but not longer. And then there is silence. And to me, that silence is amazingly beautiful, especially if the battlefield also happens to be beautiful, or the battle ends at sunset or sunrise. If you have a pointless conversation with someone, switching to this topic is extremely helpful. My memories of 1979 revolve around one such war. But I was different then, and the times were different, too.

Now we live in an era of a great war, and the battles underway today are different in form compared to the battles of old.

Speaking of which, wars never stop. For one, there’s the continue struggle for existence in the animal world. The same goes for us. It’s just that we have come up with more entertainment for ourselves, to deal with fear and psychological pressure. Look, we’re looking for aesthetics even in war.

Lado: This aesthetics vanished together with the end of the Classical period when, with the advance of the Industrial Revolution, the notion of fighter was replaced with the term soldier. At Metropolitan Museum, we have one amazing exhibition hall. Mamuka, I guess you love it, too. So, this hall showcases frescos and paintings capitalizing on the motifs of famous battles. It also displays exquisite examples of Japanese and European body armors. It has samurai weaponry and armament pieces from the period of King Henry VIII of England, also excellent paintings by Italian and German artists. I’ve read somewhere—I don’t remember where—that, during the Italian Renaissance, opposing parties would round up armies and come to face each other. Let’s say, Ferrara taking on Sienna, for example. And often the nobleman whose troops sported better-looking, more refined armament would be considered victorious. Of course, there were devastating, bloody wars, including famous ones, those depicted in the frescoes by Paolo Uccello, Michelangelo, and Leonardo, for example.

But this aesthetics have sunk into oblivion, and what do we have now in return? We got Henri Barbusse with his Under Fire, a novel about how man turns into fodder, sitting in trenches with his ugly fight helmet on and calluses on his hands. And how others, his brothers in the same lamentable condition, are bombarding him with only goal in mind, to annihilate their enemy in the trenches, to turn him into ground meat. Here we see blood, flesh wounds, but there’s not even a shred, not even the slightest idea suggesting aesthetics or form in any way. When I was drafted into the soviet army, I was given uniform and boots ugly as hell, ugly to the point of stupidity. Add to that this unbearable, despicable khaki. And, on the other hand, there have been warriors saying, “I’m not dying for money! I crave glory!” Hannibal, who fought against Rome, is one such warrior coming to mind. It must have been a gorgeous sight to see, I mean Hannibal’s war elephants and Roman tortoise formations facing off….

Mamuka: Even the noise during such battles must have sounded differently, with those pounding drums and blaring trumpets filling the air and putting psychological pressure on the enemy.

Lado: But now all it takes is the push of a button, and civilization as we know it will be gone for good. Push the button, and all of India is wiped off the face of the earth.

Mamuka: Why India of all places?

Lado: I just meant any country, Mamuka, any country, hypothetically. All right, let’s say someone pushes the button in Pakistan and, as a result, all of Europe evaporates. What I’m trying to say is that we suddenly find ourselves where we are now. The war, which we discussed in the beginning of our conversation, is a fratricidal war, and there is no button in that war. Instead, the wars in both Abkhazia and South Ossetia contain predominant elements of drama. In both cases, we see ruined human relations between neighbors and relatives, treachery, hatred, indifference…. And that’s exactly why I, as a writer, am very much interesting in reenacting wars, but not as much as an artist…. Because paintings can’t really grasp the drama.

Mamuka: All right, I get this drama and aesthetics things. But any war is conceived in someone’s twisted mind, right? Remember Thor Heyerdahl? Here’s a story about him. He happened to be visiting some tribe. And he tells the local chieftain: “I heard your people eat human flesh….” The chieftain is surprised, so he asks, “Why, you don’t eat human flesh? You don’t wage war for human flesh?” Thor replies, “No. We bury our dead in the ground.” The chieftain is in total shock: “But why do you have wars, then, if you don’t eat human flesh? We go to war, and afterward divide those killed. And you bury them in the ground? Why have wars, then?”

Lado: That tribe just can’t get their head around the idea that wars can be waged for territories, resources, oil, or space programs, for that matter. They just don’t understand our world.

Mamuka: One way or another, wars are figments of someone’s perverted imagination, conceived by sick egocentrics who are used to being applauded all the time, so they come up with all kinds of things to justify wars—citing statistics and data-base evidence to prove that wars are inevitable.

Lado: The only reason why I left Sokhumi and moved to Tbilisi was my attempt to escape war. But I had no problem moving from Tbilisi to New York and leaving Georgia behind. When I moved to Tbilisi in 1993-1994, I found hell on earth, with the police robbing people, coupons instead of money, starvation, cold. I used to take the subway, the route via Delisi Station, to the Academy of Fine Arts. And as I soon as I got out of the car, I would get my nose in a book, walking like that through the tunnel all the while, hiding from everyone and fearing that someone would recognize me. The cops didn’t give a damn, thinking that I was some kind of moron walking around and reading a book at the same time. At least, that’s what I wanted them to think, so I wouldn’t hear them calling me out: “Hey, come over here, dude!” At that time, I wanted to leave the country, but somehow never did. But then Georgia itself opened up to me, embraced me with arms wide open, and I made friends with the finest people, whom I will never lose. It feels that I have never even left. It’s a matter of time.

Mamuka: It was after Sokhumi that I realized how unbearable Tbilisi was. It seemed full of even more aggressive and unhappy people. It came across as a monoethnic and heavy environment with a great deal of egocentrism, where everyone pretended to be something, while being full of himself. Sokhumi, on the other hand, is a port city, a multiethnic city with my beloved Greeks, Circassians, Estonians, and everyone—the list goes on and on. Sokhumi gave everything I have, including music. In my mind, I seem to be looking for this city in me ever since. Wherever I have settled, Sokhumi has been part of me, be it in Bombay, San Francisco, New York, and now Adjara. In fact, Adjara is a genuine El Dorado. I have been to five deserts and seven canyons in America alone, but nothing comes even close to what we have here in Adjara.

But Tbilisi welcomed me differently each time, with its climate and all other characteristics. The most vivid experience, though, has been that of anxiety, when I left all my stuff in New York and moved to San Francisco. My biography was about to end in San Francisco. I had no idea what to expect in New York where I knew only one person, Lado.

To tell the truth, I’m constantly on the move. I was away even before and during the Abkhazian war. I was in an Indian ashram at that time. In a way, my stay there symbolized my refusal to take any part in what was happening here. It was my way of fighting. Let’s say I engaged in the war, but whom would I seek to defeat? I’m still on the move, always. If I were born and raised in Gori, for instance, I might have done things differently.

When I was in Ashram, I listened to the radio to learn the news of what was happening here during the war, and how. The coolest thing that happened to me there was that I made friends with two Abkhazian brothers. There were in fact from “the other side”, from the Mayak neighborhood in Sokhumi, of Tatar descent, if I’m not wrong—I don’t really remember. Although there were some Georgian guys too, we, those two and I, became best friends. This wonderful friendship must have been a product of intuition and, at the same time, cultural unity. While a war raged here, those two Abkhazian brothers happened to be my closest friends.

Lado: I have no fear after the war, no nightmares, or anything of that kind. Nothing brings back that anxiety. It’s just that I always look ahead, have been ever since. I get a feeling that my whole life is nothing but preparation for tomorrow. There is no today. I seem to be doing everything for tomorrow. Even that book I’m writing now is for tomorrow. I have no clue where this train of thought is coming from, maybe from the war. I don’t know.

I’m moving from New York to another city right now. I’ve already rented a fully furnished house there, so now I’m about to pack everything I have collected over these years—including my books, discs, and whatnot—and head to a storage trailer. And for me, doing that is like going through hell. Not because I may never see these books. And why should I worry? After all, there’s Cornell University where I’m going, Ivy League and all that, a school with the richest library in the world. How about that, Lado? But no, I still get this feeling of going through hell, and I guess I know why. Here I am carrying these boxes outside, emptying shelves, and yet fearing that I will lose them. This is what war has done to me. I left my home in Sokhumi with only one backpack. I just packed some stuff and left. And now I’m about to part ways with my favorite things again. And it doesn’t matter that, this time, it’s all planned, prearranged, and safe. I find it very hard. Mamuka is different. He travels around the world with just one backpack. He’s been like that for years now. I’m just learning how to travel light, but Mamuka is natural.

When I moved to Tbilisi and enrolled in the Academy of Fine Arts, I discovered that the school had its own library. I was happy as a clam in high water because now I had thousands of books at my disposal. I could bring them home and read. And it was in that library, in some Russian magazine, that I came across Six Memos for the Next Millennium, a compilation of essays by Italo Calvino. There were supposed to be six essays on literature, but the author died before he could finish the last one, explaining why there are five essays in the book, despite the title. In this book, Calvino writes about simplicity in literature and, at the same time, simplicity in life. I read that text in September of 1994, exactly two years after the Abkhazian war. In September, Sokhumi fell. Calvino describes a story of Guido Cavalcanti ridiculed by some Florentines in the period of the Italian Renaissance. And here’s what happened.

Cavalcanti is strolling at a cemetery. Suddenly, he is chased by some people who start making fun of him. They are all on horses, lit up like a Christmas tree. So, they keep mocking him: “Guido, you’re still feeling blue? You still writing poems? Come with us, Guido. There’s so much fun and pleasure in the royal court!” Guido leaps over the cemetery fence with ease and yells back: “Dear friends, I would like to, but I cannot. I have someplace else to be. Take care!” What amazed me in this story was lightness and ease. He avoided a conflict without a conflict. I wish I could be like that, I thought, I wish I could leave as easily as that, I told myself. Achieving ease, simplicity is what matters here to me.

Mamuka: Yes, I have been across the world with just a backpack. I have ascended every mountain in Abkhazia. I had my little radio receiver that accompanied me everywhere. But what pushes me forward? I have wandered off to Kazbegi and many other places. But going to India was a preplanned journey with a purpose. I wouldn’t call this journey an escape. Shortly after India, I went back to Europe. On second thought, it might have been an escape. One thing is true: I never missed Georgia. I always wanted to be far, far away.

Once, I met a Georgian immigrant, musician and pedagogue, who had jumped through some major hoops throughout his life. Botso Korisheli, he lived in California. He even created a new musical system, a whole musical system. He was of rather small stature, kind of like Mahatma Gandhi. And he asked me: “I must have traveled a lot and met multitudes of Georgians along the way. How do you get along? Are you tight?” “Not really,” I replied. “For the most part, everyone’s minding his own business.” He nodded and said, “Yes, that’s because we are mountain people. We live like eagles. And eagles don’t really get along with each other.”

“Mountains, on the other hand, are like obstacles for us. They always stand in our way,” he continued. “And you know that there’s something beyond them, something different is going on there, something that is difficult to approach and embrace. And that’s exactly why Georgians seem to fly the coop like sparrow-hawks,” he concluded. It’s a true story. I, too, used to be a quintessential cosmopolitan, but America has turned me around. America gave me a chance to do something Georgian, this something coming in the form of bread—I started baking bread.

Lado, I have told you before that I gave up buying books a long time ago. I had no idea what to do with the ones I already had. I gave away some of them, and some I keep in New York. And I have more in San Francisco and Tbilisi, also in Sokhumi. And what you just described, I mean your books on the shelves, that’s a luxury.

Lado: I don’t know about luxury, but I do know exactly where I keep the book that reminds me of you. It’s Narrow Road to the Interior by Matsuo Basho. The author describes how he traveled through the snowy landscapes of Japan with only a sack on his back. And how carried the whole universe in that small sack. This is Mamuka’s story. Mamuka is a wandering soul. My idea, on the other hand, pushes me more toward Borges and Umberto Eco. My idea is one of libraries. And libraries are my world.

Mamuka: Yes, I remember that, because I also remember that time when you had only books in your only bag that you carried with you when you left.

Lado: Yes, I even carried the Bible, despite the fact that I am not a religious person. I also had an antique icon. Later on, I donated it to a newly built church in Tskneti.

Mamuka: As for me, after so much wandering around, I want to settle down here in Adjara. I want to have a place that will bring together all these scattered pieces and create a unity. I want to build a house. And right now, I’m in the middle of this process.

Lado: When you moved from New York to Batumi, it seemed like a giant leap to me, not your typical move. It made me think of heaven on earth that people look for their entire lives without even realizing it.

At the age of 52, I’m reading Grigol Robakidze’s prose for the first time, namely The Snake's Skin. Meeting the lead character of this book has had a tremendous influence on me. It’s about a Georgian on his deathbed in Persia, requesting a fistful of earth from his homeland. And I guess that’s exactly what you are talking about. We the Georgians are the children of a small country, and sometimes we, albeit unconsciously, tend to infatuate with foreign countries. Remember how we, as kids, thought that the West, the land abroad, was a magical world, an inaccessible land of plenty? Now we know this longed-for West like the palm of our hands. We have seen what life is about, we have been places, and we have solved some puzzles. But that’s it. Now we know that shmucks and lowlifes are everywhere, and with equal statistics per capita, and so are corruption, poverty, and sadness found everywhere you look.

Mamuka: That mysticism, which you just mentioned in reference to puzzles, seem to turn up where traditions exist. But, in the Western world, everything is so precise and particular that any quests in this rigidness of everyday life are dead in the water. I often notice that, when Georgians talk about their homeland, they seem to keep others wondering, if not envying. Not many people are as attached to their homeland. But our people draw on and draw strength from myths.

You see, we’ve managed to have a dialogue, after all. And dialogue is a quintessential European style of communication. That’s another thing that makes us different. You prefer the East and mysticism, but I have a penchant for Europe, logic, and rationalism, despite the fact that I love the East too—in the early 1990s, I used to chant Indian mantras. I guess our inner worlds are two extreme points with the Georgian mentality roaming freely in between. It’s like the Western aspect of the East and, at the same time, something along the lines of the Eastern hues of the West.

Mamuka: Human beings are limited in their abilities. And we tend to ignore nature, because we think that nature is some outsider observing our lives, something flourishing on its own. In reality, however, nobody and nothing exists here on its own. We will never understand anything, even ourselves, until we regulate this interaction.

And that simplicity, which you were talking about earlier, it contains, among other things, so much wisdom, right? Your Guido confronting those fops reminds me of the story of one samurai poet. Here it goes. This samurai is walking down the road, deeply absorbed in thought, composing verses while he’s at it. At some point, he brushes past another samurai, accidentally touching him with his shoulder. That other samurai hates poetry, so he unsheathes his sword and says, “You have insulted me by intentionally bumping into me, and now I must kill you.” The samurai poet, a skillful swordsman himself, doesn’t feel like crossing swords, fighting and all that—he’d rather be writing poetry. But what can he do? How does he get off the hook? Then he asks, “Who would you be?” “I am a glorious samurai who wins with two swings of his sword. And who are you?” returns the question the cocky samurai. The poet replies, “I am a samurai who wins without fighting.” Suddenly, they notice a boat with just enough space for one passenger. The poet makes an offer: “Let’s fight on the other side. There’s more than enough room for dueling, and that’s where I will shed your blood.” The belligerent samurai agrees. And the poet adds, “I’ll take this boat to the other side. Once I’m on the riverbank, I’ll send it back to you.” But, after having reached the other side, he drags the boat ashore. The rude samurai shouts at him: “You coward! Running away from me, aren’t you? You should perform hara-kiri and kill yourself!” But the samurai poet replies, “No, I just defeated you without fighting!”

Lado: Mamuka, you know there is China, and there is this book, The Art of War by Sun Tzu. It’s an outstanding treatise on warfare tactics. And the very first rule of warfare goes something like this: If you can defeat your enemy without a fight, then you should do so. Here, I found the page. Look, “The supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting. Thus, the highest form of generalship is to balk the enemy's plans… and winning without fighting.”

Mamuka: That’s exactly what I intend to do right now by building a garden I can call my own. My personal Zen is about to happen here in Adjara It is here that I want to end this war. Better still, I want to have both. What is war? Constant change, and what is the other thing? Perpetual peace and quiet. Breathe in. Breathe out. It’s my project, and that’s how I see my house in Adjara.

Lado: You remind me of Voltaire’s Candide. After all kinds of adventures, he comes home. And what does he do? He builds a garden.

Mamuka: What was the name of that Roman emperor? The one who, after endless military campaigns and twenty years at the helm of the empire, said that all he wanted to do was to build a vegetable garden and grow cabbages….

This is the nature of our nature. It incorporates both. From what I have learned, and the way I see it, we are dealing with dualism here. Look, breathing is possible only when you breathe in and breathe out. Just breathing in won’t do. You must also have breathing out. If either is missing, then there is no breathing. You can’t say that you’re breathing if you inhale and then stop.

Lado: If I’m not mistaken, Lewis Carroll, in his Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, has one of the animals say: “‘I breathe when I sleep,” to which another one replies, “You might just as well say ‘I sleep when I breathe.’”

Mamuka: It’s all about continuous transitions and interchanges back and forth. Zhuang Zhou wrote long ago: “Once upon a time, I slept and dreamed I was a butterfly, fluttering hither and thither, to all intents and purposes a butterfly. Soon I awaked, and there I was, veritably myself again. Now I do not know whether I was then a man dreaming I was a butterfly, or whether I am now a butterfly, dreaming I am a man.