Repeating Mamardashvili | Essay 16 – Anamnesis of the Vanguished, of the Repressed

Some time ago, late at night, together with a friend we discussed the obstacles about envisioning a future. We didn't just talk about the individual and yet social-politically imposed restrictions between one's dreams and one's actual possibilities and/or impossibilities, but rather about the restriction of creating a vision as a community, as a society. A vision, or visions, that are not just fleeting accumulations of keywords, which have become so deeply embedded in one's understanding of what life should or could be. But a vision, or visions, that carry the spark of utopia within, that make striving for them, despite the obstacles, an endeavour worth taking on.

Why does it seem so difficult to look towards the future? It is always just a breath away, hence not as intangible as it might seem at first, when positioned at distance. Time can feel overwhelming, both in its vastness and limitations, time at first is intangible, only at moments there is a brush of understanding when the past touches the present touches the future, or all three merge into one at one specific time, one specific moment, maybe a turning point, maybe a point of stagnation.

That night, we arrived at an understanding that this trouble with the future is once again linked to our engagement with the past. The selection of what we see and accept as our past and the impatience with which we tend to press for the 'now'.

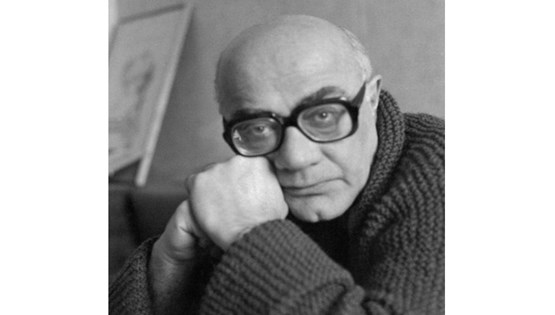

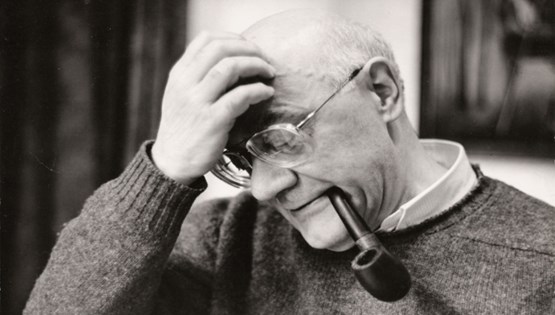

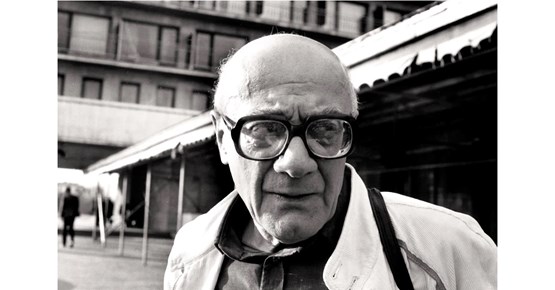

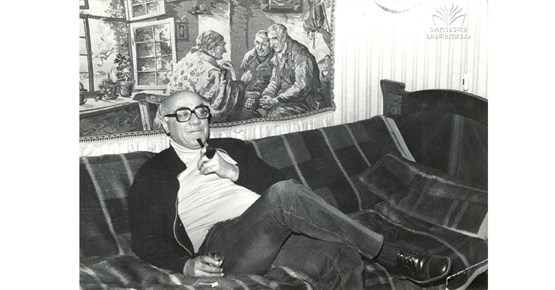

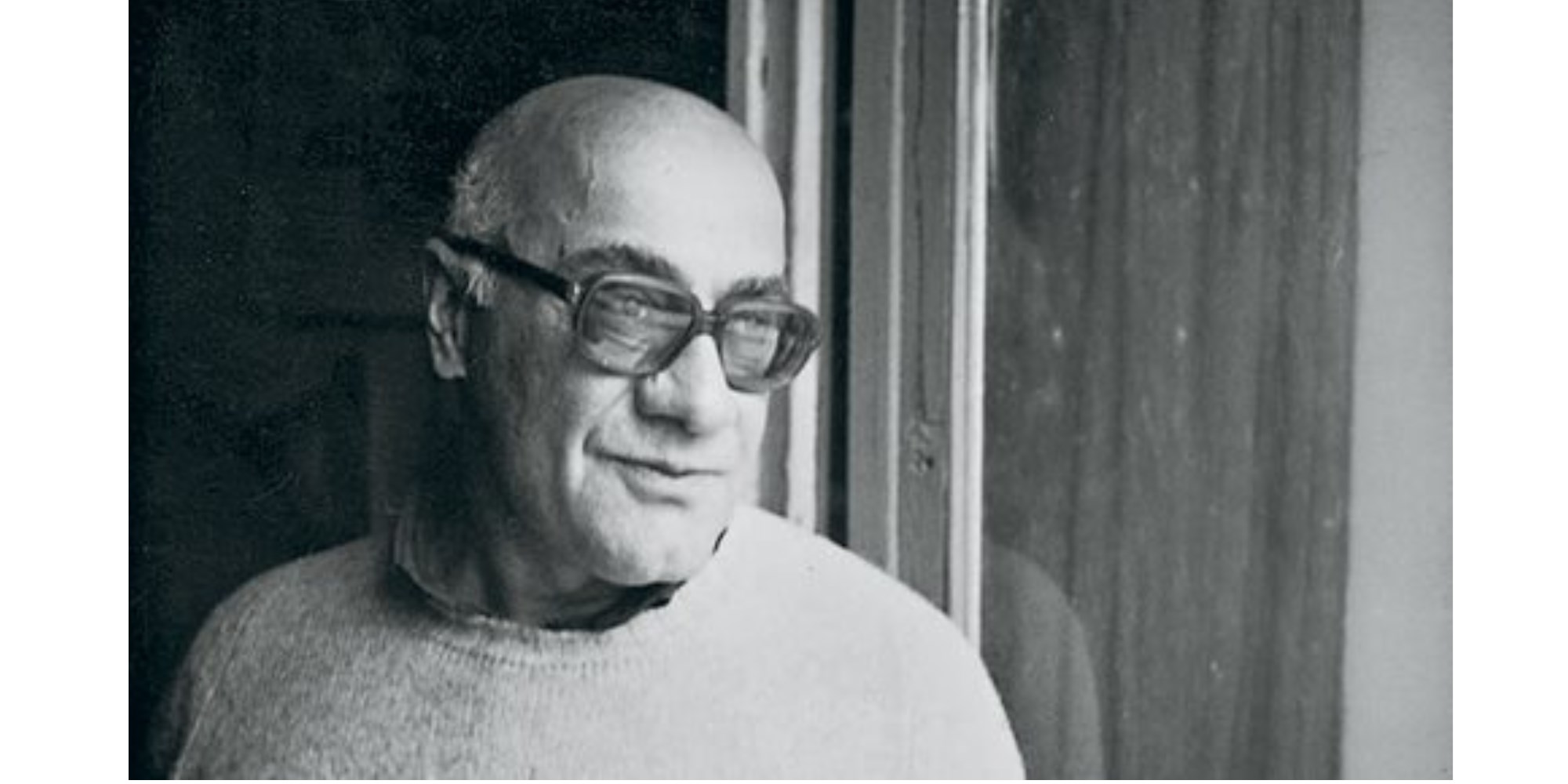

My friend asked if I see my work on Merab Mamardashvili in this context, an attempt to highlight someone's work in the past as a link to the future. I couldn't, at first, answer the question. But in the sense of that his work is not well enough known, definitely yes. And we talked about others. For instance, my fascination with the ski jumper Koba Tsakadze from Bakuriani and his successes at the Four Hills Tournament, winning two hills on January 6, 1956 (Innsbruck) and on January 1, 1961 (Garmisch-Partenkirchen), not listing here his other places on the podium. A tournament that I have been watching since my childhood, four dates in my calendar each year, never to be canceled. And all of this led me to Bakuriani two years ago to take photos of the dilapidating structures of its former hills… My friend told me about Glakho Zaqaryan, a singer from Tbilisi who I had not heard of before. She spoke about his self-trained voice and showed me, among others, a recording in a kitchen, him singing and playing the doli, accompanied by a duduk, or maybe rather, them singing together?

When we next met, we had both been following up on Koba Tsakadze and Glakho Zaqaryan respectively. I had watched and listened over and over again to those kitchen recordings, trying to put my finger on why his singing resonates so strongly. Well, for me, and my friend obviously. And she had been watching interviews with Koba Tsakadze and told me with fascination how his style of ski jumping, his style of flying was inspired by his experience of watching eagles flying as a child.

Do these encounters make our potentiality of envisioning a future stronger? At first, maybe not yet. But if we all collected and connected, individually and/or collectively, those and many other references of achievements, but of course also of disasters, known or always already invisible, if we allowed these to materialize in one way or another, at times, as something to come back to, to rely on, to build upon or to tear down, think of Sans Soleil for instance, well, if…

The other day I read a quote from Theodor Adorno's Aesthetic Theory as one of two epigraphs in the book The Theatre of Death – The Uncanny in Mimesis. Tadeusz Kantor, Aby Warburg, and an Iconology of the Actor. In the introduction '[t]he reader is invited to revisit these epigraphs when dipping in and out of the chapters that follow' – and so Adorno wrote: 'The primacy of the object is affirmed aesthetically only in the character of art as the unconscious writing of history, as anamnesis of the vanquished, of the repressed, and perhaps of what is possible.'

And it is these last six words, 'and perhaps of what is possible,' which don't assert certainty, but affirm the chance that there is hope after all.

Twitchin, Mischa. The Theatre of Death – The Uncanny in Mimesis. Tadeusz Kantor, Aby Warburg, and an Iconology of the Actor. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

Author: Katharina Stadler