A Riddle You Must Solve | Interview with Gvantsa Jishkariani

Words like division, polarization are heard all over the place. And indignation over injustice is welling up among the people of this young republic. The pandemic adds insult to injury. But what stands out in this chaos most is polarization, opinion polarization.

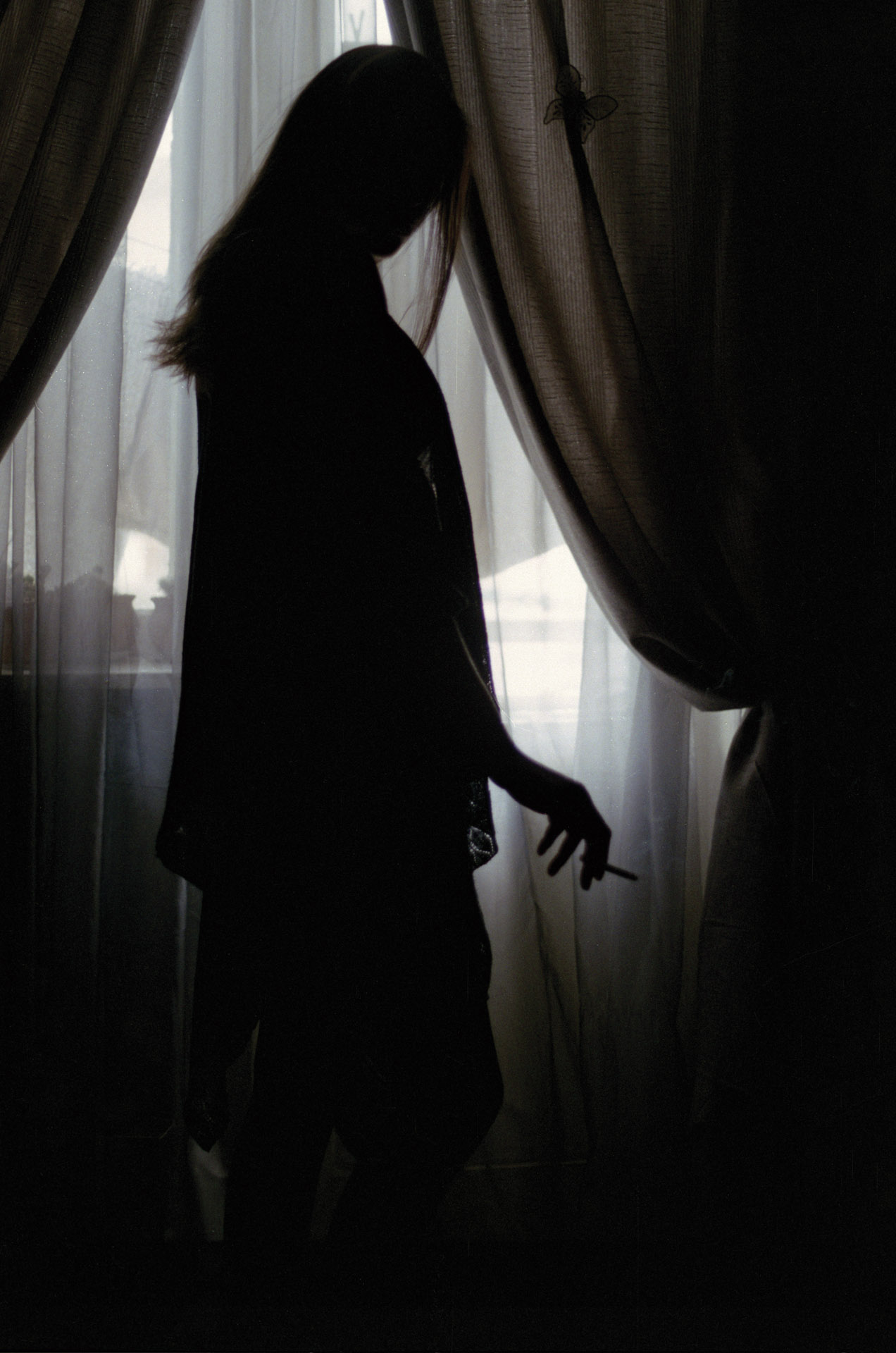

We have teamed up with artist/curator and founder of Patara Gallery and The Why Not Gallery Gvantsa Jishkariani to discuss how everyday anxiety and fear translates into contemporary artworks.

G.J.: It happens often that, when I decide to translate ideas into physical reality, I can never link them to particular times, facts, or events. I grasp them as much as I can tell them from 40 daily thoughts, but I find it hard to tie them to something in particular, unlike the works from the Tapestry series that I started in 2018. Although they’ve changed over the years, every time I think about it, I realize that what brings them all together is a particular source of fear, one from my childhood. I was born and raised in a poor family, and there was a Ssoviet tapestry on the faded wall of our living room as a physical embodiment of my complexes of adolescence… and poverty and need, therefore a symbol of my fear of vulnerability. When I think about this uncomfortable material or story of mine, I cannot put it into words, so I take a different route, and I have my visual works to show for it. At the end of the day, a concrete work turns into a controllable fear from my childhood.

N.K.: Are there any collective anxieties that older and younger generations share?

G.J.: I notice more unconscious, untamed fear among older generations, something we, too, have inherited quite well. Fear of something that is hard to come by, for example, something you can’t get unless you hustle a little. One of my acquaintances told me that everyone in his neighborhood owned the most fashionable car’s latest model, but 1% could actually use it, because the rest could not afford gas. That they absolutely had to have a car tells me that it’s all related to fear of restrictions on private property rights. Next, this fear gives rise to the mechanism of obtaining a social status. As a result, we have a tragicomically ridiculous culture of flaunting.

Self-censorship is another thing we have in common, and not just in arts, but in every form of expression. Culture in general is full of self-censorship, the reason why people, often unconsciously, shackle their minds in certain norms. And that triggers a conscious fear of authentic self-expression, a process that takes place in an individual at first and then in society. In the recent past—let’s say, in the Soviet Union, for example—several institutions defining identity mutated. The institution of the tamada toastmaster comes to mind as an esoteric and metaphysical phenomenon prior to sovietization, a form of interaction above standard in every way. But under the Soviet Union, the institution of the tamada toastmaster, similar to viticulture, degraded to become something mundane, routine, thus killing authenticity and, consequently, giving rise to self-censorship. And that’s exactly how a particular Ssoviet model of behavior—meaningless, coerced, red-tape, and unauthentic—developed to become a second nature for entire generations. This is why contemporary behavior, among many other things, is mostly a struggle against negating the obvious, that is, a fear that today’s relations may prove fake, too.

N.K.: Hyper-normalization, a term coined in the 1980s, denotes an environment in which everyone knows that nothing is being done fairly, that the country is on the verge of collapse, in which everyone, including the ruling force, knows that the real power is not in their hands, but everyone turns a blind eye nonetheless. Madness is normalized, and distrust is overwhelming to give birth to opinion polarization. Under these circumstances, people often conclude that artists alienate themselves from social protest.

G.J.: In reality, things are quite different. Any valuable artwork is directly or indirectly tied to politics. My political art is the gallery I curate. It is also my social product. Generally, political art is often caricature-like. I don’t want to draw a caricature. Why should I if I can do politics through my work? Patara Gallery is also a political act, self-organized and non-commercial, a space renovated with our own hands and opened in an underground passageway as an example of exiting one’s comfort zone and doing what one wants to do in the most unimaginable of places.

At the time we opened Patara Gallery, there were only two or three similar establishments operating in Tbilisi, and even those positioned as salons or worked exclusively with their own artists, meaning that they didn’t accept young, struggling creatives. There were smaller ones like Window Project that involved showcasing works in street display windows, a breakthrough in its own way… but mostly carnival silence filled galleries. The oppressive silence of contemporary art always instilled fear in me, a fear of the system created by such galleries. I always try to distance myself from these settings.

N.K.: Nowadays, my list of the key sources of fear among young people is as follows: A) criminal police, B) political instability as a norm, and C) daily struggle for sustenance.

G, J.: There must be others, too. For my brother and me, for example, these were family debts that seriously affected us, and I’m sure most of our generation is the same way. Also, many people, especially young girls, are having a hard time dealing with the norms of behavior here. For example, I believe that the fear of not being accepted—or, to be correct, my protests against this fear—has defined my clothing style. Walking in the street is dangerous for young girls. I have witnessed repeatedly how young women sitting next to me on a minibus were cursed out, and everyone turned a blind eye. That, too, should be blamed on opinion polarization. There is nothing more Georgian than to keep your mouth shut unless it concerns you directly. This is my fear of navigating among people who are friends with fear. There is also police inaction. In some cases, cop act so that they might as well be absent. But I think that fear of change is the biggest one nowadays, especially now that ultranationalist politics is on the rise globally. I have learned from experience that you are at your best when you can adapt to changes. Most importantly, you must survive in this constantly changing environment. Losing comfort is painful and yet rewarding. Knowing that nothing lasts forever makes your stronger. We have survived so far and created a thing or two in the process, proving that we are fantastically strong. And fear, too, is ultimately a puzzle you must solve.

We Recommend

Fear as a Political Factor

17.03.2022