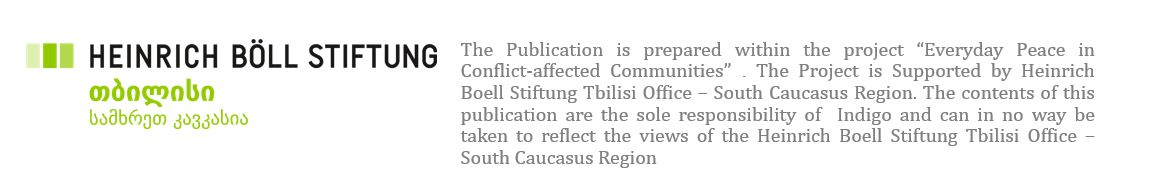

My Grandma | Nukri Tabidze

My grandma watches the tube all day,

Flirting with Adriano Celentano;

My grandma loves flesh-color lipstick,

I wonder what stories she tells to her Italian friend.

One time, she told us to take her home in Ochamchire.

My grandma slowly forgets where she is,

And she forgets my grandpa too.

That’s why she keeps two cloves of garlic in her pocket.

The brownish-yellowish skin—

Dried, solidified, and grown into the clove—

Yes, the two cloves of garlic

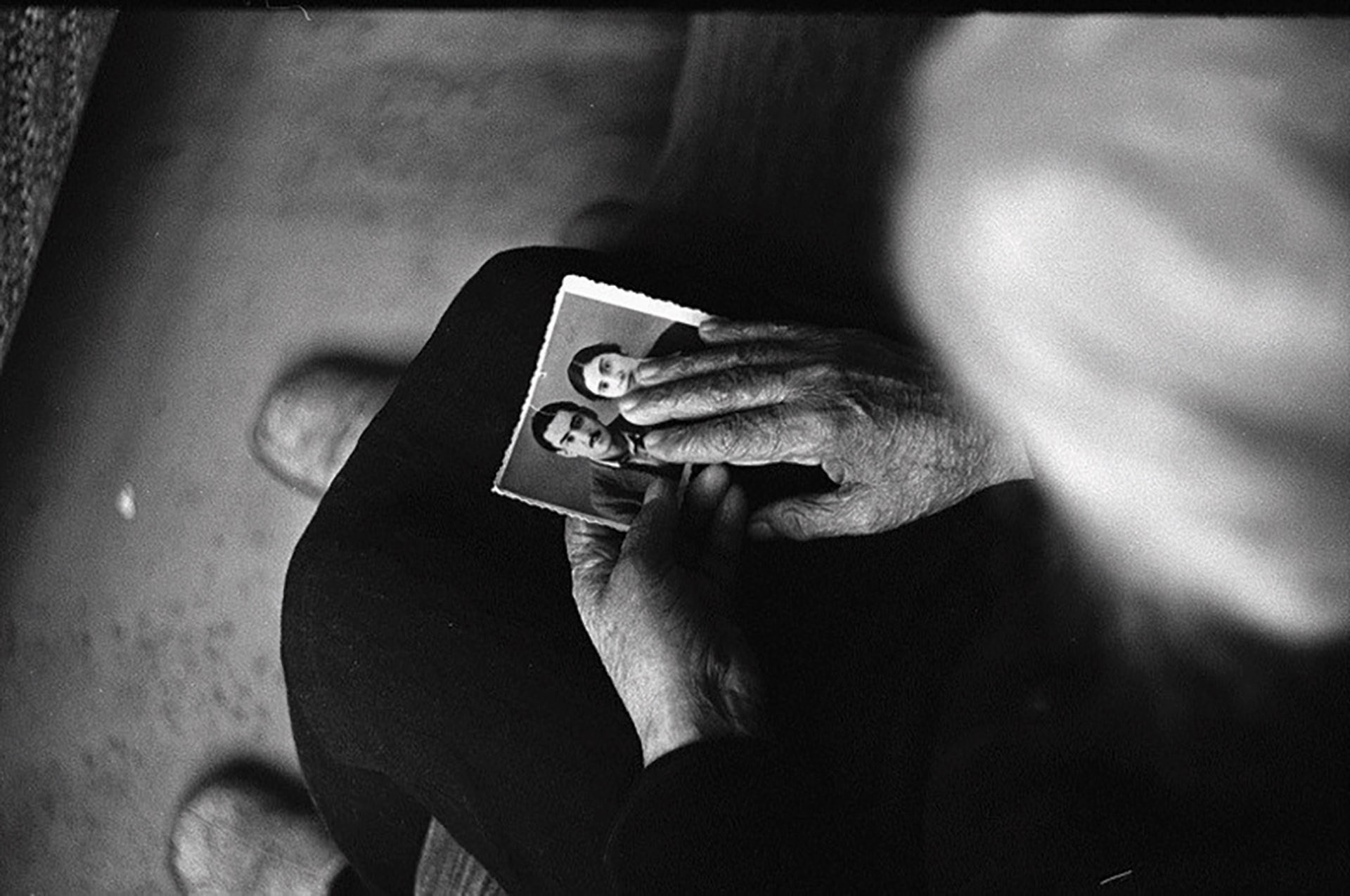

She once discovered in her dead husband’s pocket.

He used to say they kept a cold away.

And now my grandma keeps them like some lucky charms.

She listens to music and bangs her hands or sometimes cane

On piano keyboards.

Sometimes she sings.

She even chanted incantations to ward of COVID-19:

“Charidamao Dadioma, Charidamao Dadioma,

Mshvenier COVID tak zojunsi, iagudi do lalebi.”

She cannot remember the words, but she still finds comfort

And forgets her sorrows, my mother spells it out for me.

And she turns to me:

“It must feel soothing, right?’

She loves Italian music.

One time, she met one Italian tourist in Borjomi.

She spoke to him in Russian for an hour,

Though the tourist did not speak Russian.

She opened up her enormous purse—

Her bittersweet purse of mammoth proportions—

Where she kept her medication and lipstick.

She gave the tourist some Imodium.

I did not know how to say diarrhea in English,

But everyone in that sanatorium would be intoxicated.

Your grandma loves her medications,

My mother used to say—and that in fact was not too hard to guess.

I could never understand how would someone love medications

Or why!

But NO-SPA and Rehydron from her purse

Seemed not as astringent in childhood.

She can hit the vein blindfolded, they used to say about my grandma.

Now she was no longer a nurse, nor could she find a vein, but

Medications, her medications are just as yummy as before.

And now she carries them from room to room in a small plastic bag,

Together with old newspapers, threads, and loose papers.

The other day, she clipped out some man’s photo from a newspaper.

I asked her who it was.

And she replied, “A spine doctor, and I will let him rest

Here on his beloved belted plaid, and “let him rest” she did,

Some man’s picture like an icon.

She was hurting all the time—that may be why she crazy about doctors,

Or maybe because she was herself a nurse.

How does it feel to be constantly in someone else’s shadow, someone who you’ll never be?

Nobody believed her pain,

Even herself,

Until she became a wreck, half the woman she used to be,

Until (selectively) she forgot all.

We used to think she was a hypochondriac.

But then this COVID started, and everyone went hypochondriac.

That may be why she stopped wining—I just don’t know.

But before she greeted me with

“It hurts right here in my knee,” “this back’s just killing me”—

Hurting all over.

The war was to be blame for it all,

Or maybe it was sneaking across the River Enguri in winter.

That’s what my mother used to say.

But grandma never mentioned the war

And never complained about the depth or coldness of the Enguri.

She had to mourn her young nephew after all!

She could not miss her sister’s funeral, how could she?

Her life, unlike my parents’, did not end in 1993,

And I have no idea what she witnessed in that war

To make her never mention it all,

Or miss her Ochamchire, sea breeze,

Her garden, wattles, ivies—

Because something always reminds everyone of home.

In fall, the city would be mined

With false memories.

My grandma did not want her ivies,

Nor did she miss her garden,

Or long for a better life.

And whatever grief she seemed unable to contain,

Along with ivies and fall breeze,

She did transform into a meniscus in her knee and hernia in her back,

Into benign tumors of the liver and kidneys,

And into constant worries about wrong diagnoses

From wrong doctors.

Those she had lost she did forget,

And those of us around her were never enough.

And when she really could no longer sleep because of pain,

She stopped worrying at once.

Unlike others, she would not hold onto the past.

Daily anxieties,

Checking blood pressure three times a day,

Then drinking coffee only to reduce her heightened blood pressure—

She quit it all.

She made new friends

Somewhere on YouTube

And old torn magazine pieces.

My mother cursed the day I gave an old laptop to my grandma:

“This thing has driven her mad,” my mother thought at first.

But when my mother I saw grandma

In fear of contaminating Celentano,

She carefully sneaked up on her to turn the laptop off.

Shortly thereafter, though, she did turn it back on,

And later even taught her how to handle it.

“He’s already dead, you cannot give him anything,”

My mother said.

But grandma would not believe her.

And then I said, “You are not contagious anymore,”

But she would not believe me either.

And then we chatted for a while,

Enjoyed our grits and cheese, I even peeled for her a tangerine,

And then she said, “I’m tired,” proceeding to lie next to that “icon.”

Photo: Mano Svanidze