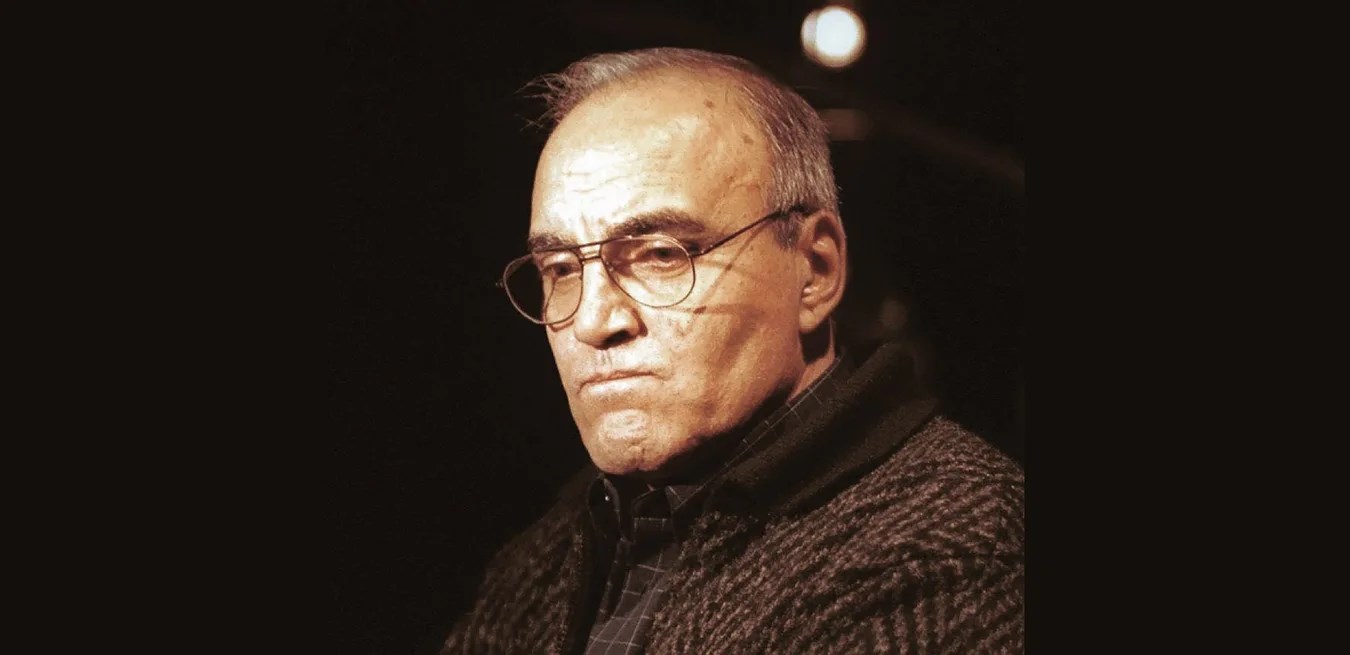

Buzzing, Pathos, and a Chunk of Ham | Interview with director Temur Chkheidze

For two years, I met Temur Chkheidze twice a week at Royal District Theater. I was part of a team studying theater as a system for processing life. We held discussions in an attempt to what made our work as important as emptying dumpsters, baking bread, and playing with kids. I’m sitting in a car with my teacher, whom I haven’t seen in years. The car is parked behind Rustaveli Theater.

A. Ch.: Trotsky, in the final years of his life, wrote that “Old age is the most unexpected of all things that happen to a man.” Philosopher Emil Cioran commented on these words: “If, as a young man, he had had the exact, visceral intuition of this truth, what a miserable revolutionary he would have made!” Has age sneaked up on you, too? What does age bring?T. Ch.: Do we ever reevaluate anything? No. We just become more conciliatory, so to speak. Not that you put up with everything. You just realize that you must forgive others and, more importantly, recognize if you are the one in the wrong. It’s not that your nature changes. It’s your attitude toward one thing or another that changes. It’s your response that changes. That’s what age brings. I remember how my mother used to say, “Learn to forgive. People make mistakes, but you shouldn’t walk all over them.” How true! But, at the time, I wondered how one can forgive everything. I don’t know. I don’t know so many things. Honestly, I hoped my mind would open up to far more things. But I’m still the same fool I’ve always been

A.Ch.: You often say: evolution, not revolution. How did you arrive at this assertion?

T.Ch.: I was surprised myself when I realized that this was my philosophy since youth. It’s a matter of principle. I wasn’t just against conflicts. Unfounded claims also irritated me. After all, we don’t assess a statue from one angle only. We walk around it and look at it from different angles. How can you not see your or other people’s deeds from different angles? Or be more forgiving? “What is the most important thing in arts?” someone once asked Rodin. I love what he said in response: “What do you mean what? Who, not what!”

I got polio when I was three. My right arm never developed. Because of my health condition and physical appearance, fist-fighting was out of question. Those around me always protected me, doted over me, making sure I didn’t get hurt. Even when playing, they made sure I didn’t fall, because I could damage my right arm beyond repair.

A.Ch.: A year ago, I visited my grandfather—using COVID as an excuse, because I rarely go see him—and he recalled one story: “My neighbors had buffalos”—he was born and raised in Abkhazia—“Sometimes they herded them down the river toward the sea. Once, the buffaloes wound up in the sea, pretty far, and couldn’t come back. I felt sorry for my neighbors, so I jumped into the raging sea and pushed their destitute buffaloes ashore.” He told this story like it happened the day before. And it dawned on me that this story had turned into a myth for him, one he frequently returned to. Do you have such memories?

T. Ch.: My parents had a tiny, one-story villa in Shekvetili. Once, we thought we were drowning, and we the drowning were my mother, my sister Maka, Kote Makharadze, and I. Here’s what happened. Desolate beach. Kote says, “Let’s not swim today. The sea seems wrong.” All right, we won’t. I was sitting there, minding my own business, reading a book. Shortly, Kote calls me: “Temur!” I stop reading and look toward Kote. He’s standing near the shore, knee-deep in the water, tossing up Maka and skillfully catching her in mid-air, pretending to be ballet dancing. I go back to reading. Then Kote shouts at me again: “Temur!” He’s tossing her up again. Big deal! She’s only like 30 pounds or so. Then again: “Temur!” But this time the voice comes from further away. I look and see that, although they’re on the shore, they cannot get out of the water. It’s high tide, and the water has washed away the sand under their feet. I get into the water and reach out to Maka, but she refuses and tells me to help mother first. “Give me your hand, mom!” But mother is afraid that she may drag me with her if she clutches my hand. We’re all shouting. Kote resists my help more than the rest. “Get out!” he yells. “Let me see you swim!” “But I can’t, Kote!” I shout back. And there’s my mom on one side, and there’s Maka on the other…. And suddenly Kote freezes. Waves keep rolling one after another. He raises his head and bellows: “God, help me! Save my child!” And I realized that I was witnessing pathos in the making. It is born out of dire straits. And now when people ridicule pathos, I say nothing but still protest in my heart: You have not seen genuine pathos.

A.Ch.: A few days ago, my little son crawled up the stage in Mziuri Park’s amphitheater, standing in the middle, spreading his arms, and shouting: “Gods!” Then he took a pause and added: “Gods, bare your butts!” Where there is pathos there is also comedy…. Where there is hell, there’s also hope, albeit smuggled one. You mentioned once that, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, pathologically fervent hope emerged.

T. Ch.: Still, freedom is better, however distorted, however flawed…. Of course, that is a far cry from the ideals and expectations we had….

A.Ch.: Now that you’re evaluating things, how do you think all this aggression has welled up?

Ch.: People have not arrived at anything. They’ve always been there. It’s just that the circumstances were not right. And after all, it’s no picnic demolishing and then rebuilding everything. It’s easy to judge. But you should start with yourself and ask: Have I done everything the way I thought I would? And I’m not talking about building a life for yourself. I’m talking about mistakes, voluntary or involuntary. Half of our mistakes are involuntary, those that we realize only later. But even if I can go back, I’ll make the same mistakes, because I am what I am.

For example, everyone is a believer in Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible. But they understand faith and truthfulness differently, and they ruin one another, right? The main character is told that he’s about to be hanged in an hour, and if he wants to survive, all he has to do is sign a confession and admit ties to the devil. “They’re all dead, so their fate no longer depends on you. Just sign it, that’s all.” But this man resists to the end, unable to decide. And that’s the way it should be, because man doesn’t live by directives. He just wants to live. That’s what he was made for. And what does he say? “I have three children—how may I teach them to walk like men in the world, and I sold my friends?”

Back when I was a student, one man, a former Gulag prisoner, told me: “They beat us so badly that I’m surprised I recognize you. There are two things that can happen when you’re tortured in interrogation. Either you confess to everything, or you get spasms and won’t be able to say a word. People say about me that I wouldn’t snitch on anyone. Yes, it’s flattering, but it’s not something I should be credited for. I just had spasms. When they tortured me, I was reduced to non-human. So, don’t judge anyone who’s been through this.”

A.Ch.: That reminds me of Snow, a poem by Robert Frost. Nightfall. It’s snowing. A young couple are making ready for bed, and suddenly someone knocks on the door. They open the door. It’s a priest, a willful, odd man. They’re not happy to see him. The priest is on his way home, but it’s snowing like crazy. The priest calls his wife to let his wife k now where he is. The wife asks him to stay where he is, because it’s a long way home. And the young couple offer him to stay overnight, but it’s also clear that they’re not happy about it. And the priest leaves. At midnight, the phone rings. It’s the priest’s wife asking about her husband. In fact, that’s where the most important part of the poem starts. Regret kicks in. The couple feel remorse over letting the priest leave in such weather. Willing to sacrifice themselves, they set out to look for him.

T. Ch.: By the way, that poem could make a good play. What’s the key idea behind The Ballad of the Tiger and the Lad? “At least I’ve raised one son to war against the tigers.” This one? No. “Or maybe the tiger’s mother is weeping harder than I am, so maybe I should go see her and join her in mourning.” That’s the one. That’s the gist of the poem. It would’ve been worth nothing if it stopped on the line about raising a valiant lad. Yes, she’s proud, and it’s good that she’s proud, but she goes further than that. She goes to see the tiger’s mother. That’s the philosophy I’m talking about.

I’ve never been a dissident or government supporter. I always wanted to live minding my own business in peace and quiet. My wife tells me: “All you want is sitting at home.” But what else could I want? I read when I’m home. I can’t go on walking in the street and reading at the same time. And why is it mandatory to go somewhere? I’ve been like this since childhood. I don’t get bored when I’m alone.

A.Ch.: But your life hasn’t been that easy. For example, during the war in 2008, you were in Tbilisi, but then you moved to Petersburg to work in a theater. And it proved difficult for you to return. It took you some time.

T. Ch.: It’s very difficult when things happen in your home…. That’s why I made that decision to leave because of the theater, because of the people who worked there. Guram Odisharia, in one his novel, describes a dog running amid Sokhumi’s bombing, so the dog is wondering if the whole world belongs only to human beings. I would rephrase: “Does the whole world belong only to politicians?” It shouldn’t be the way it’s in The Great Dictator, when he is toying with the globe.

Once, I found an old faded book, an explanatory dictionary, in my aunt’s library. I opened it at random and came across morality. What is morality? It’s the ability to put public interests above one’s own. That’s it.

A.Ch.: What do you make out in these crises besides this struggle?

T. Ch.: It happened in the 1990s. No electricity. Night. Suddenly there’s a knock on my door. I open the door. It’s Eldar holding a chunk of ham in his hand. “Guram Lortkipanidze gave it to me, but I can’t eat alone, can I? Let’s boil it and enjoy together.” Then he told me something I remember to this day. “When I was little, that’s how we would gather, some bringing pickles, others a bottle of wine, and a whole meal would appear on the table. What else could we do? We couldn’t wait for better times to knock on our door!” And now this pandemic has divided us, but there are also many examples of people helping each other.

A.Ch.: After vaccination, we were put in a waiting room. An elderly mother and her daughter were sitting in front of me. They were at an age when the difference is blurred between parents and children. The mother’s wait time expired, and she was told she could leave. “Let me stay and wait for my daughter,” she asked, holding her daughter by the hand. They sat like that and waited together. I don’t know why, but I could hardly hold back tears.

T. Ch.: I was touring Germany once together with a Russian theater. It happened in Weimar. After the performance, the local theater held a reception. I was the only Georgian present. A gray-haired woman accompanied by an interpreter approached me: “So, you’re that Georgian, aren’t you? I came to watch the play because of you. Please give me a few minutes.” “Of course.” And then she tells me this story: “I was in 7th or 8th grade when WWII broke out. We, a German family, lived in Sokhumi. My father was a music school principal. Soon we received an order giving us two days to pack. They were going to round up all the Germans in town and herd them to Central Asia. There was this boy, a senior student in my school, that I liked. His last name was Maisuradze. During breaks, I kept searching for him with my eyes. But he wouldn’t approach me to introduce himself, and I couldn’t do that, of course, hnow could I? Two days passed, so they gathered us up and took us to the railroad station. Soldiers lined up along the platform. A freight train standing by. They threw us into the train cars. Silence. Nobody’s crying. And suddenly I see that boy. He walked up to the soldiers and told them something. Probably five minutes later, which seemed like forever to me, and I don’t know what he told them, but they let him through. He’s looking for me. I disembark, and finally we meet. We didn’t know what to tell each other, so we just stood looking at each other. I don’t know where he is or if he’s alive, at all that boy Maisuradze. But I do know that he’s the only man who has risked his life for me….” As long as tears fill our eyes at such stories, nothing will disappear and nothing will be lost.

A.Ch.: I often recall your story, that one about the elevator rumbling and buzzing nonstop as you were staging a play. Gia Kancheli recorded that sound, and you used it at the play’s climactic moment. The audience couldn’t even hear this buzzing that disappeared in the right time to let deafening silence take over, as though emphasizing the importance of this silence. So, I think that this buzzing, one that we often fail to hear, accompanies our entire lives, and one day it will disappear. Can one be prepared for that?

T. Ch.: Don’t bother. You can’t prepare anyway. It won’t work. Because we don’t know the most important thing, which is when it is time for us to check out. And it’s good that we don’t know it. You have no idea how I regret objecting to my mother: “Mother, how can you forgive everything?” “As time goes by, you will understand it all,” she said. And time has gone by.

We Recommend